It was somewhere between the fifth and sixth hour in the registration queue that I began seriously to question my decision-making abilities. Of all the strange choices I’d made over the years, this was definitely one I was sure I’d regret. I couldn’t quite wrap my head around the fact that I had signed up for this voluntarily. What the hell I was doing here?

‘Here’ was National Youth Service Corp (NYSC) orientation camp. Launched in 1973 as a way to involve university graduates in the development of Nigeria, NYSC is an integral part of Nigerian life. The three-week camp is aimed at preparing us ‘corpers’, as we’re known, for the year-long scheme, where we’re deployed or ‘posted’ to different states across the country on an assignment aka a job (based on our university discipline) in one of three sectors: education, agriculture or governance.

Was the wheel breaking off my suitcase moments ago a sign of what lay ahead? I looked at the drab ageing buildings; the soldiers in their uniforms scattered across the parade ground; and then back to the swollen crowd. I picked up my suitcase and walked towards the mass of people. Thousands of twenty-somethings were standing, sitting and in some cases lying on the ground in what I could only assume was meant to be a queue.

In Nigeria cash is king and if you have enough of it the country is your personal fiefdom.

I had fallen for my dad’s sales pitch and moved to Lagos but why I had gone a step further and signed away a year of my life to serve a country I’d never lived in was anyone’s guess. Up until some months ago I was living a comfortable Nigerian-lite life in the diaspora. I knew about my culture (kind of), I knew about the country (sort of) and I was pretty content with that.

Nigerians from the diaspora taking part in NYSC is nothing new; dozens fly over to do it every year, some convinced of its eventual necessity by their parents, others in a bid to aid their transition into Nigerian society. I use the term ‘taking part’ loosely. In Nigeria cash is king and if you have enough of it the country is your personal fiefdom. And the NYSC programme is no different. Money can buy you your way out of camp, your posting, or the service entirely.

Before my posting, I had to get through camp, which had taken on an almost mythical status in my mind.

That whole pooping in a bag and tossing it somewhere was surely just a myth, right? Right?

My parents met at camp, something my grandma keenly reminded my ever-so-single self before I set off. And then there were the tales. Would I really be sharing a room with 30 strangers? Would people really be trying to steal my underwear? Did I really have to wear a bumbag everywhere including the toilet? Would I have to fetch water and march for hours on end? What about shot putting? That whole pooping in a bag and tossing it somewhere was surely just a myth, right? Right?

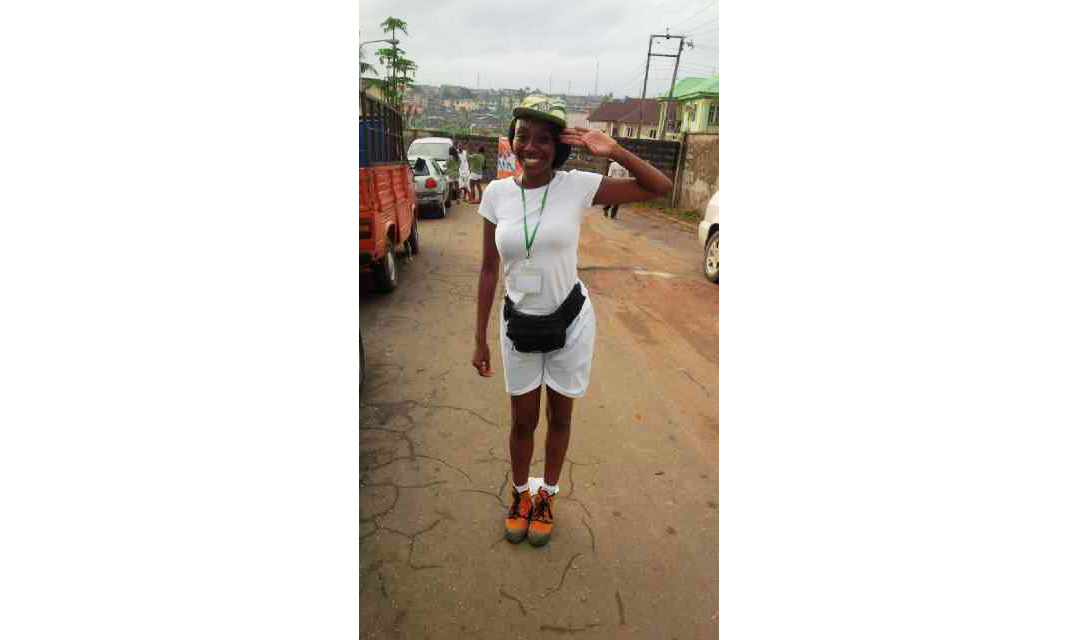

As I picked up my ill-fitting uniform after ten hours in the registration queue I couldn’t stop wondering, what, if anything, was to gain from this.

After the first week of camp I still didn’t know. There were toilets but I hadn’t quite decided if that was a pro or a con. Being woken up at 4am by the sound of a bugle was definitely a con, as was sharing a room with 28 women. It was rainy season so it rained… a lot, and we had to march in the rain, a lot. There were endless lectures, possibly more than my entire university education. Some of the officials clearly enjoyed making our lives miserable and everything smelt of pee.

I felt like I was on one of those Survivor-type reality shows but with no money or trophy at the end.

Socialising, which I only began to do properly after about day eight, was my saving grace. Of course having beer on tap and scheduling my bathroom visits helped but meeting corpers and soldiers from across the country quickly turned camp from a bad horror movie to a dark comedy. Three weeks sped by and my marching days were over almost as soon as they had begun.

Now it was time for actual service. Like the majority of corpers I was posted to a public school, and the idea that the educational fate of about a hundred teenagers lay in my inexperienced hands made me feel distinctly uneasy. I’d never taught before and apparently lacked the aggression to survive the ‘mean streets’ of Lagos public school.

As with camp there were a lot of stories about service

I’d be teaching ‘kids’ who would actually be older than me. They’d be rude and aggressive. The male students would harass me; the female students would disrespect me. The teachers would be a nightmare; the classrooms would be crappy. The officials would be corrupt; the bureaucracy endless. Plus I had a British accent so I’d have to cough up money. Just because.

Sometimes after class some of the kids would tell us about their dreams of conquering the world and how they couldn’t wait to grow up and be corpers like us.

Just like camp there were nuggets of truth in a sea of half-truths. The facilities were sub-par, the officials corrupt, the bureaucracy overwhelming. But teaching the kids, or learning from them as I did was an eye opening experience about the reality of the city I was living in. A lot of the kids I taught were from low-income backgrounds or worked as maids, sent down to Lagos by their families who were living in states where education isn’t free. Sometimes after class some of the kids would tell us about their dreams of conquering the world and how they couldn’t wait to grow up and be corpers like us.

Being a corper is a part of the Nigerian experience. It’s seen as the last stage of tertiary education, the final hurdle, and the key to the world of employment. Hearing the kids long for it wistfully made me sad and exasperated.

NYSC is a great idea; in a country so vast and complex there is a need for some sort of unifying ideal to bridge massive gulfs between groups.

How would NYSC tackle the staggering youth unemployment rate? Or equip corpers with employability skills? Or even fulfill its basic aim to include Nigerian youth in the development of Nigeria?

NYSC is a great idea; in a country so vast and complex there is a need for some sort of unifying ideal or something to bridge what can sometimes seem like a massive gulf between groups. The problem is that this particular idea is broken and like so many broken things in Nigeria it has been reduced to a way for groups of people to make money; its original purpose as lost as it is redundant.

Thousands and thousands of corpers are churned out batch after batch, year after year. They have the keys to the world in their hands only to find out they open very few doors. NYSC may be a lesson in society but in practical terms I’m yet to see the real point. Given that the scheme’s original aim is out of the window, it would make sense to either tweak it to make it more relevant e.g. providing real opportunities in emerging sectors as opposed to using corpers as band aids to cover the bullet-riddled infrastructure. Or the answer might be to abolish it altogether and using the money for a comprehensive graduate job plan. Instead there are rumours of the scheme being extended to 18 months, with six months reserved for paramilitary training.

I always knew that if I wanted to, I could walk away from NYSC with nothing more than a bad feeling and the hope that perhaps things would get better.

Personally I learned a lot from NYSC; it was absolutely worth it and I’m sure many former corpers would say the same. Being a foreigner it was like year-long course in understanding the Nigerian system beyond the ‘Africa rising’ headlines. But my experience, like others who ‘come back to serve’ was different from the majority of people taking part. I never felt as though service was a compulsory part of my life and I knew my employment chances didn’t rest on whether or not I had an NYSC certificate. I always knew that if I wanted to, I could walk away with nothing more than a bad feeling and the hope that perhaps, one day, things would get better.

Sooner than I expected the year was up and I was at a Police College waiting to pick up my certificate. The mood was cheerful despite the downpour. After a few hours it was finally time for me to bribe my local government official with a gift, just because. I handed it over happily, ready to finally resume my life.