The offspring of famous politicians often choose public service as a natural career path. After all, a famous surname guarantees a certain amount of brand recognition, as well as access to natural allies who are eager to carry on the fight. As the daughter of Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president and a black liberation icon, Samia Nkrumah was well aware of her pedigree and she did enter active politics.

She hopes to make a pitch for the leadership once again, in order to claim the mantle of true Nkrumaism

She was a Member of Parliament for the Convention People’s Party (CPP) from 2008 to 2012, and the national Chairperson of that Party from 2011 to 2015. She says she is afraid of the current Party leadership. She believes it has veered off from her father’s ideas and is only using his good name to muster some credibility.

Together with like-minded members of CPP, she hopes to make a pitch for the leadership once again, in order to claim the mantle of true Nkrumaism and turn the Party into a Pan-Africanist political force.

Her current mission leading the Kwame Nkrumah Library and Pan-African Centre can be summarised as a concerted effort to preserve her father’s legacy, in order to nurture a new generation of political leadership, in Ghana and elsewhere in Africa. Even since she returned to settle back in Accra almost a decade ago, she has been developing her capacities in this regard.

During the weekend preceding today’s 60thanniversary independence celebrations all over Ghana, I had a telephone conversation and a series of email exchanges with her. I found her to be aware and informed, conscious that her opinions as a custodian of a major part of African history are crucial to the process of truth-finding.

As we talked over the possibilities—and shattered dreams—behind Ghana’s post-Independence idealism, I realised that she has been working frantically for most of her adult life, figuring out new ways to research and coordinate information, in order to share the knowledge.

A couple of days ago, we published an article by a young Ghanaian writer named Isaac Inkum who is planning a biopic on your father. Have you met him and his group of aspiring film-makers?

Yes, I have. And I agree that a feature film is long overdue. There are many reasons for this. Kwame Nkrumah was a powerful leader. His main aim was to make Africa politically and economically independent. In voicing his plans out loud, with passion, with the range of his thought as an intellectual and philosopher, he stepped on some powerful toes in the process.

He thought those powerful interests were making Africa poor.

In 1965, he published Neo-Colonialism, and that book angered some very powerful interests. He thought those powerful interests were making Africa poor. What he started doing in Ghana was to change the structure of our economy from a colonial one to a modern, industrialised one. But he did choose socialism, and he put in place a series of economic and development plans. His socialist leanings, in addition to his call for African unity, and the force with which he rallied some African countries, that scared some people badly.

In 1966, there was an illegal and violent overthrow of his government. This was against the constitution, an overthrow of our first democratically elected government. After that happened Kwame Nkrumah was seriously vilified, and his books were burned. This occurred when his Encyclopedia Africana was supposed to have been compiled and produced in Africa, by Africans and Africans in America whom we sometimes refer to as African Americans. His African unity project, and his economic independence project, where we, as Africans, would control our resources and our economy, these were courageous, bold steps.

Given his clout and personality, it is possible that he could have gone far with those plans, even beyond the fact that he was one of the five leaders of the Non-Aligned Nations, alongside Nehru and Sukarno. As history would have it, many of these leaders disappeared in the mid-to-late nineteen sixties or early seventies. Kwame Nkrumah had links and tentacles everywhere.

Powerful systems wanted Nkrumah out, because they were aware of his mission to emancipate Africa.

I am determined to make his writings, books, speeches and plans available in abundance in Africa. We believe his ideas are still relevant to our problems today. There is a still a case to be made for us Africans to own a bigger share of our natural and mineral resources. When you look at the ownership structures, usually, we own between 10 and 20 per cent of our oil resources here in Ghana, and even less than that from our gold, for example.

Could it be that Nkrumah was isolated within Africa, which might have led to his downfall?

First, we must discuss the reason for his overthrow. The reasons are very clear. He was always a target, and even suffered eight assassination attempts since the beginning of his political career.

Some high-ranking Ghanaian police and army, and even the civil service, and many of those who studied in military colleges in the UK and Europe, they had what he called a colonial mentality, looking up to the West for ideas and direction. And then there was external interference. The declassified documents show that the CIA was involved in his overthrow. Powerful systems wanted Nkrumah out, because they were aware of his mission to emancipate Africa.

He was a committed Pan-Africanist who understood very well that our countries would be weak if they didn’t have that kind of union.

Concerning other African leaders, Kwame Nkrumah always maintained that our African countries were too small to survive economically. If we remained separate, we would have to sell out and become dominated again, economically and politically as well. Alternatively, we could plan our development together and work together. Some African leaders were not of the same level of awareness as Kwame Nkrumah, and they didn’t understand or support him fully.

We also have to look at the inability of the Organisation for African Unity—of which he was a founding leader and which is now the African Union—to carry out his proposals for a common market, a common currency and monetary zone across Africa. Just like he wanted economic integration on a continental scale, he also wanted to see African countries having a common foreign policy position and defence system, in order to minimise outside interference.

He was a committed Pan-Africanist who understood very well that our countries would be weak if they didn’t have that kind of union, that we would be too fragile to withstand the pressure to control us again from outside. As a result, the African unity movement suffered terribly after his exit, even though he laid the foundation for unity by supporting and showing total commitment to many of the African liberation movements.

If he had stayed on, he would have kept at it until a nucleus developed. Ultimately, he became the main target. When the strongest leader is weakened, the whole project suffers. They were out to get him for many years, and they got him, finally. He was one of those who were targeted all along.

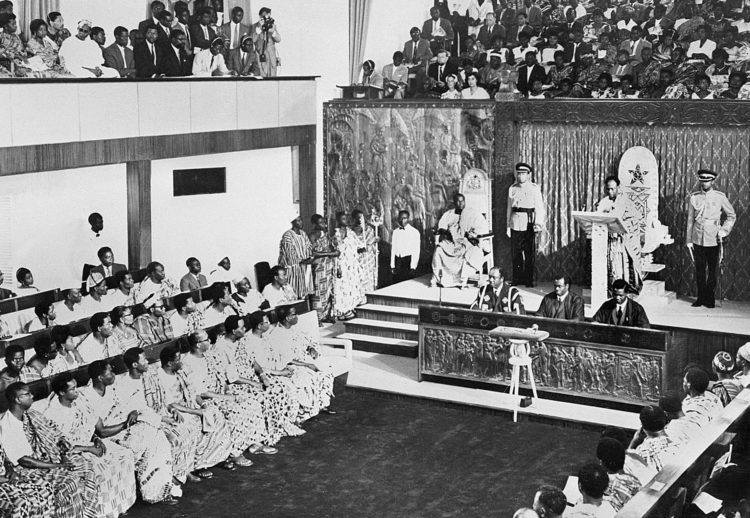

I always remind people that Martin Luther King attended your father’s inauguration in Accra in 1957. That was 60 years ago, and many people don’t know that the civil rights leaders in America were inspired by what was happening in Ghana.

For Kwame Nkrumah, the seed of Pan-Africanism was sown in America, during his student days. When he became head of state in Ghana he brought the brilliant African American scholar William Alphaeus Hunton to be secretary to the Encyclopedia Africana project.

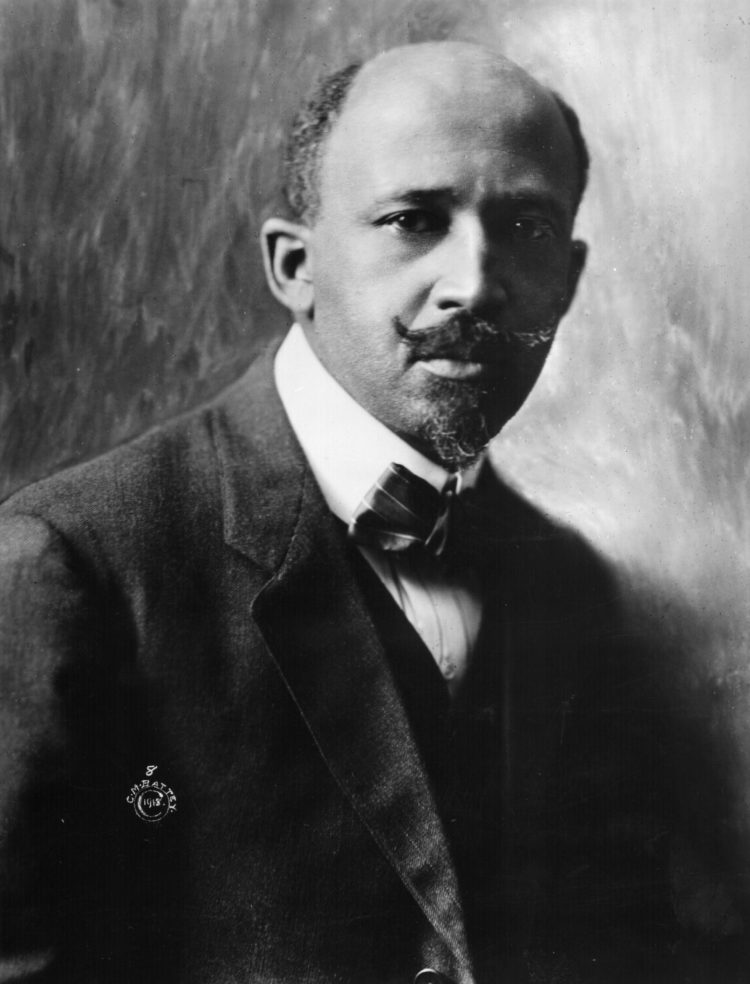

And W.E.B. Du Bois came to Ghana at his invitation to spend his last years here. Du Bois had proposed the idea for the Encyclopedia back in 1909 but couldn’t get any support for it until he came to Ghana and devoted himself to the preparatory work for the Encyclopedia.

We need to go back and understand what galvanised those independence leaders. We need that same force today.

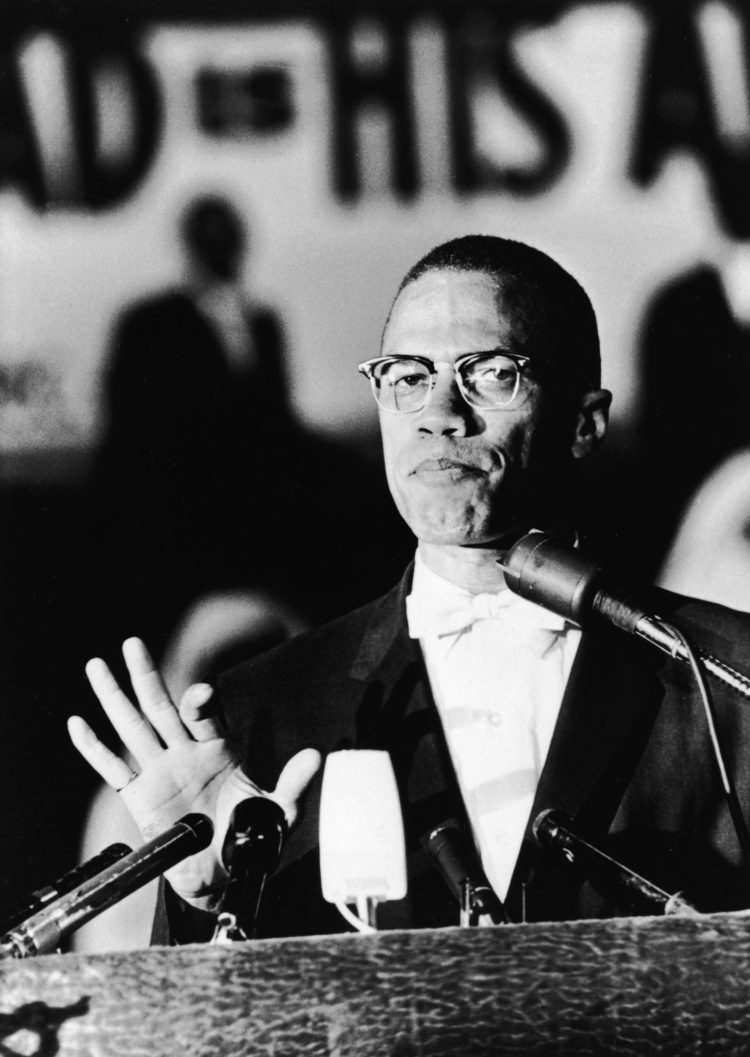

Nkrumah talks about all this in his book Dark Days in Ghana, which was published in 1968. He also said, in his autobiography, that of all the literature he studied the book that did more than any other to fire his imagination was The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey. He had very strong links in America, and many black personalities came to Ghana after our independence, including Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King and Richard Nixon met in Ghana, in 1957. At the time, Richard Nixon came to Ghana’s independence celebrations as the head of the official American delegation. In those days, those two men would have never met in America.

There is a famous story. On the eve of Ghana’s independence when Kwame Nkrumah declared us as a free, new nation, Nixon said to a man standing next to him, just as everyone was watching the fireworks, “Isn’t it great to be free?” This black man answered, ‘I wouldn’t know, I’m from Alabama.’

I remember seeing our father coming into the house with his clothes covered in blood.

Martin Luther King had a great sermon entitled Birth of a New Nation, which he delivered in April 1957, not long after he returned from Ghana. The independence movement in Africa had such a strong influence on the civil rights leaders in America. When Malcolm X came to Ghana in 1964, he said that black Americans were very proud of what was happening in Ghana.

Kwame Nkrumah always maintained those links. Many people don’t know that W.E.B. Du Bois died in Accra, at the age of 95 while he was working on that Encyclopedia Africana. There is so much in our history we don’t examine. That same passion and zeal we had in that exciting period of our history, is what we need today as we battle lack of development and economic marginalisation all over Africa.

We need to go back and understand what galvanised those independence leaders. We need that same force today.

What kind of childhood memories do you have of your father?

I wasn’t aware of everything that he was doing. My father was around, but he was very busy as you can imagine. We children would run around playing while he was reading or eating. I remember him talking, walking with us in the garden, and sometimes laughing, just like any normal father would do. But we also had pictures in our home, and we would ask questions when we saw pictures of people like Che Guevara. We asked and found out that they met in 1964, in Ghana.

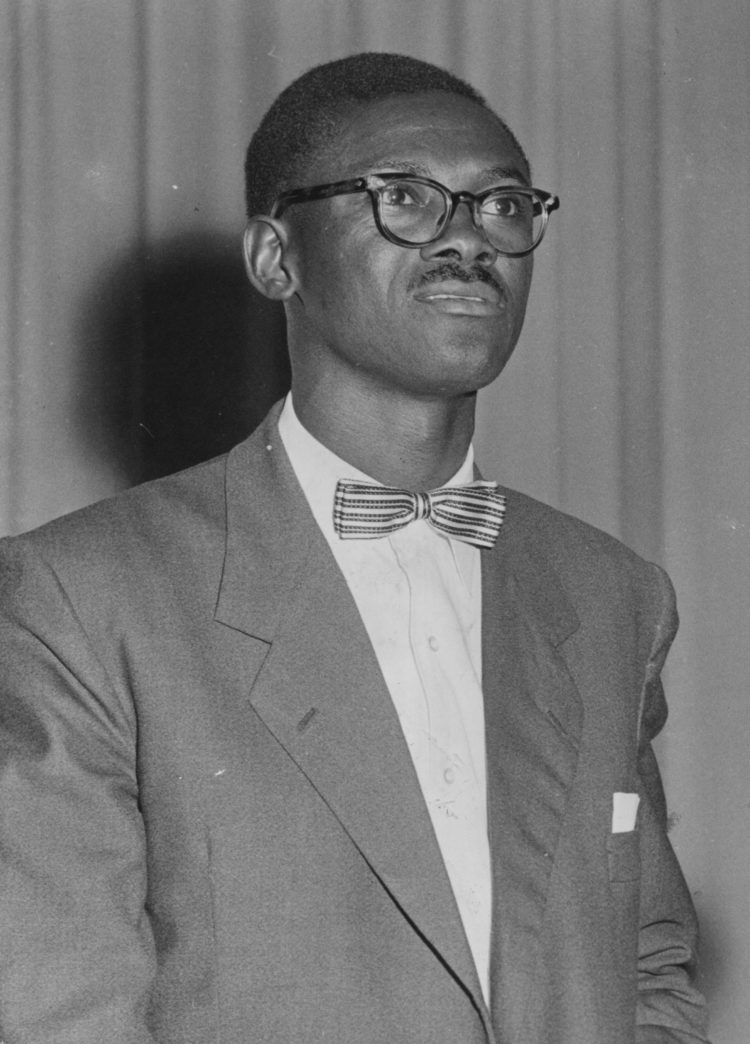

I found a picture of Patrice Lumumba. I asked, ‘Who is this man?’ I got to know Kwame Nkrumah through his writings, and by interviewing people who worked with him. Unfortunately, I have unpleasant memories as well, like the assassination attempt that happened in Flagstaff House, the official residence where we lived.

I remember seeing our father coming into the house with his clothes covered in blood. And of course, I remember very well what happened the day of the overthrow. Mercifully, we were flown to Cairo (where our mother is from) on an Egyptair flight at the end of an exhausting day. You got an idea that big things were happening around us.

We lived in Cairo from 1966 to 1975, and after that, a different Ghanaian military government invited us to come back. My brothers and I, we went to secondary school in Ghana. In the early eighties, not long after Rawlings’ second coup, our mother went back to Egypt. I went to England, where my brother was, then I returned to Egypt. I kept on moving, living in different countries, in Italy too, until I decided, in 2008, to move back home and settle, and contribute to the revival of our father’s vision.