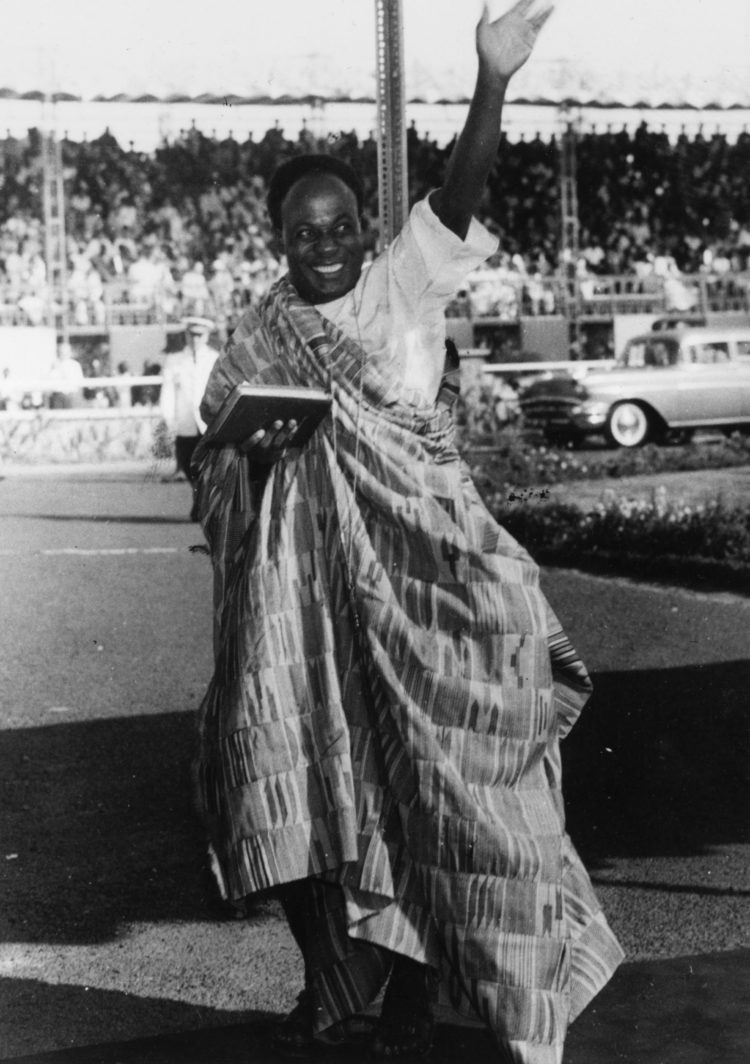

By 1957, the tiny colony on the coast of Africa had painstakingly shaped itself into a sovereign nation. It was no more referred to as the Gold Coast but Ghana. The citizens no longer recited the anthem of colonial masters. A new one was composed and sung under a beautiful flag: red, gold and green, emblazoned with a black star.

It has been 60 years now since Ghana was one of the first countries to gain independence, under the auspices of Dr Kwame Nkrumah, one of the first black presidents of a liberated African state.

Ghana is the gateway to Africa: the events of 1957 inspired other African states to fight for their independence. ‘We are going to see that we create our own African personality and identity,’ Nkrumah proclaimed to those thousands of Ghanaians who had assembled at the Old Polo grounds on the eve of independence.

Our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent.

‘We again rededicate ourselves in the struggle to emancipate other countries in Africa; for our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent.’

He supported other African states in gaining their freedom from colonial masters. In 1958 only eight African countries were independent. By 1960, seventeen African countries had gained independence. Nkrumah certainly paved the way for the others to follow.

Ghana was teaching the African Americans a lesson in 1957.

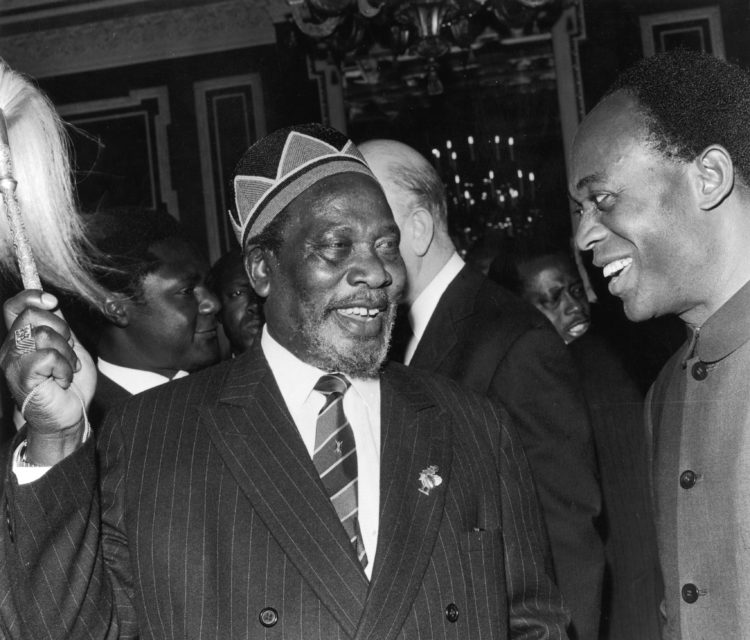

When we say the others, we mean: Sékou Touré of Guinea (1958); Nnamdi Azikiwe of Nigeria (1960); Sylvanus Olympio of Togo (1960); Patrice Lumumba of DR. Congo (1960); Julius Nyerere of Tanzania (1961); Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya (1963); Nelson Mandela of South Africa in 1994; and even Martin Luther King, the most celebrated civil rights activist of all time.

King was in Ghana for the independence celebration. He travelled back to America and delivered a powerful sermon in Montgomery ‘The Birth of a New Nation’. King spoke of how an African called Kwame Nkrumah was able to mobilize his people, survive prison and eventually lead his people to gain independence from Britain. Ghana was teaching the African Americans a lesson in 1957.

When Muhammed Ali visited Nkrumah in the ’60s, he quipped amusingly, ‘You (Nkrumah) are the greatest in Africa and Ali is the greatest in the world.’

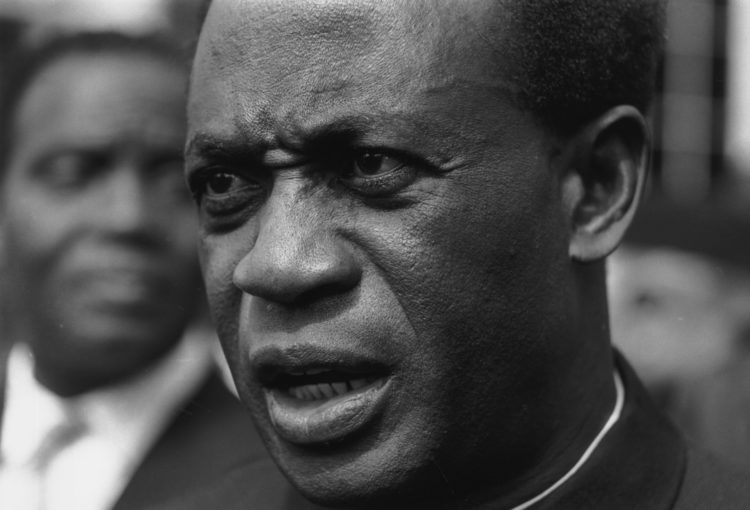

But hold on! Who is this man Nkrumah? Is he greater than Nelson Mandela? Are his words and charm as engraved in our minds as Martin Luther King’s? Is he more revered than Mahatma Gandhi? These questions inspired us, young citizens of Ghana, to dedicate our time to staging a biopic of Nkrumah.

If Obama’s legacy is analysed, Nkrumah should open that analysis.

For 50 years later, the biopic of Martin Luther King, Selma, gave the 21st century African American generation a chance to admire and learn about King. Without him there would have been no Barack Obama.

If Obama’s legacy is analysed, Nkrumah, who first drew the attention of the world to the potential of black people, should open that analysis. Obama bowed out of the Oval Office in January 2017, 60 years after Nkrumah became the first black President of the first sub-Saharan nation. Ghana celebrates her 60th independence anniversary on March 6, 2017. History is on the move.

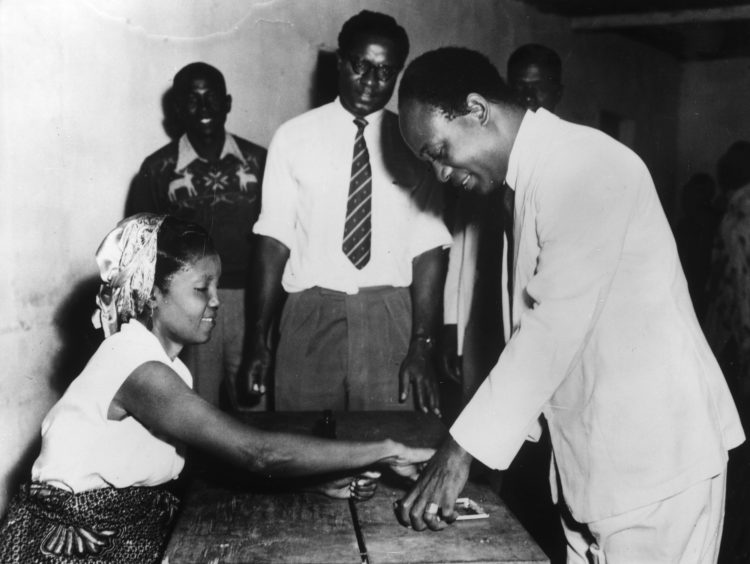

Five years ago, I started research on a biopic of the first African president. I started speaking to his contemporaries and his colleagues. The first draft of the script has just been written. This biopic will be the first of its kind to ever be done on this iconic African leader.

It will be a look at his achievements and failures. Kwame Nkrumah was a quintessential African leader who always had something to offer the people. He offered a benevolent smile, titillating oratory and a dream to see Africa unite.

He was also no saint. He played Russia and America off each other, which eventually led to his overthrow in 1966. We can learn from his mistakes as much as his achievements. That is what a biopic of Nkrumah offers. It is a look to the future.

His dream to see Africa unite politically and economically is not yet a reality. The leaders of Africa for 60 years have struggled in finding a workable approach to realise Nkrumah’s dreams. According to Nkrumah, the answer to Africa’s problems lies in unity. If the states in Africa unite, Africa can be the continent Nkrumah dreamt of when he, in 1958, organised the first conference for all independent African states in Accra.

And if there was ever a leader who valued the potential of young people, it was Nkrumah.

In his famous eve of independence speech, he said, ‘As young as we are, we are prepared to lay our own foundation.’ In times where the quality of leadership in Africa has been questioned and found wanting, we the young can only take a look at the life of Kwame Nkrumah to remind ourselves and other young people that Africa did have a great leader who not only spoke of greatness but did great things.

He had a vision for Africa that was beyond his generation.

Reflecting on his life in a film will prod us to believe that as young Africans, when we push ourselves beyond where others perceive to be our only capability, we can transform our challenges into opportunities for the benefit of all.

We have neglected the Nkrumah story for a long time. Kwame Nkrumah deserves a biopic after 60 years. He was a real African who had so much confidence in Africans. He had a vision for Africa that was beyond his generation. He was a useful citizen and a player in the world. In the Congo war, he became a peacemaker. In Biafra, he worked for peace. In Vietnam, Nkrumah called for freedom and justice. If everyone was looking at Ghana in 1957, it was because of Kwame Nkrumah. His works inspired and continues to inspire.

When Ghana celebrates her 60th independence anniversary on the March 6, 2017, Nkrumah will be the reference point.