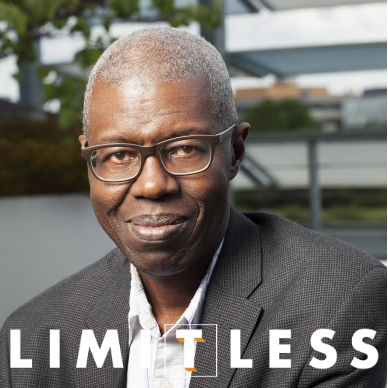

“This is not a war of religions” - Philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne on the Middle East crisis

With guests Souleymane Bachir Diagne

Episode notes

“Look for the humanism of Ubuntu.”

Transcript

Souleymane Bachir Diagne is one of the foremost scholars of Islamic and African philosophy. Currently a professor at Columbia University in New York, he remains deeply connected to the continent and to his home country Senegal. Before moving to the US, he taught in the humanities department at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar for 20 years.

During our conversation, he gave illuminatin...

Souleymane Bachir Diagne is one of the foremost scholars of Islamic and African philosophy. Currently a professor at Columbia University in New York, he remains deeply connected to the continent and to his home country Senegal. Before moving to the US, he taught in the humanities department at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar for 20 years.

During our conversation, he gave illuminating historical context to the democratic crisis in Senegal. He explained why Senegalese democracy is so resilient. This interview was recorded before the election so forgive us for not discussing the result.

We also talked about the situation in Israel and Gaza and the relationship between Jews and Muslims. We also discussed the wedge this conflict has driven between the black and Jewish communities. And we talked a lot about the concept of Ubuntu, the idea of a common humanity, and how that idea can help us frame our attitude towards the current conflict in the Middle East.

Please listen to a previous episode: Does Black Lives Matter matter to Africa?

Transcript:

“Look for the humanism of Ubuntu” – Philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne on Gaza

“And even in a situation like that is situation of genocide, a situation of massacre, they were able to try to move on to try some Ubuntu, to try some forgiveness.”

[main intro] Welcome to Limitless, the podcast that asks the questions that matter for Africa. We’re looking for African solutions to African problems. The Limitless Podcast is supported by the U.S. Department of State and the Seenfire Foundation. [main intro end]

CLAUDE:

Souleymane Bachir Diagne is one of the foremost scholars of Islamic and African philosophy. He is currently a professor at Columbia University in New York but he remains deeply connected to the continent and to his home country Senegal. Before moving to the US, he taught in the humanities department at Cheikh Anta Diop University in Dakar for 20 years.

During our conversation, he gave illuminating historical context to the democratic crisis in Senegal. He explained how Senegalese democracy is so resilient. This interview was recorded before the election so forgive us for not discussing the result.

But we started off the conversation speaking about international affairs… We talked about the situation in Israel and Gaza and the relationship between Jews, and Muslims. We also discussed the wedge this conflict has driven between the black and jewish communities. And we talked a lot about the concept of Ubuntu, the idea of a common humanity, and how that idea can help us frame our attitude towards the current conflict in the Middle East.

CLAUDE:

Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Welcome to limitless Africa.

SOULEYMANE:

Thank you for having me.

CLAUDE:

Well, it’s great to talk to you again. What is your analysis of that electoral crisis in Senegal, your home country,?

SOULEYMANE:

First, let me give some general background and look at the history of Senegalese democracy and explain why this situation is really really frustrating. Senegal is well, Senegal has been presented as an exception in on the African continent democratic exception on the African continent. This can be understood and explain actually, by the history of Senegal Senegal is had this special standing during colonial times because you had filed for cities in Senegal, whose inhabitants were French citizens, non French subjects were French citizens, meaning that they held elections, they to elect their own representatives, mayors, for example of the cities of sand we DACA or risk or IRA, those were the cities whose inhabitants were French citizens, and also they were holding elections to send their representative to the French Parliament.

So there was a tradition of elections and a tradition of democracy in Senegal, even if it was not the totality of Senegal but only those four cities, it was a very important tradition and cynics Senegal has inherited that situation. And this is the reason why even though at one point, Senegal followed, the rest of Africa in having a one party system, Senghor the first president was never comfortable with that situation. And very quickly, after 10 years of having that one-party system, he decided that Senegal should go back to a multiparty system. So what I’m saying here is that Senegalese democracy is deeply rooted in the culture of Senegalese people.

And this is why this what happened recently, when the elections were postponed at the last minute. That was just a shock to Senegalese people… One measure of Senegalese democracy, that election had always been held, according to what we might call the Republican calendar.

CLAUDE:

Now today I want to talk to you about what’s happening in the world, geopolitically. So let’s start with Israel and Gaza. We really would love to have your analysis of that situation.

SOULEYMANE:

It’s a very, very difficult situation in the first place. With so many people dead now. We see so much atrocity going on on both sides. I remember having been shocked after October 7, and unfortunately, I am still being shocked now with the amount of death in the Gaza Strip. It’s about time that the rest of the world just decides that enough is enough and that one solution has to be found for this ongoing war that has lasted for, what the past 70 years. Hopefully hopefully, to just go towards a solution of this conflict. And just go for two states and understand that the Palestinian people must have their own state next to Israel. That’s one thing.

The second thing to connect this with Africa, our African continent. I think it is a huge something huge has happened when South Africa decided to just go to the international court and accuse Israel of genocide. One can discuss the content of this but the fact that this was an initiative coming from a country like South Africa, coming from the Global South, coming from our own African continent, is something very, very consequential and I believe that the consequences are going to be seen and read in the coming in the in the coming years. And it is really a turning point in our geopolitical world as it is.

CLAUDE:

I know that many people have commented on the importance of this lawsuit that was brought about by South Africa against Israel when they accused Israel of genocide. But there’s also South Africa’s own history with truth and reconciliation. Do you think that the leaders on both sides can learn from the South African process of truth and reconciliation as promoted by people like Desmond Tutu, and that continues with a specific tradition now?

SOULEYMANE:

I do think so. And actually the concept of Ubuntu that South Africa has constructed as a philosophical, ethical and legal concept of reparative justice, the idea of restorative justice and transitional justice, the idea that at one point, the the only good answer, to tragedy, to atrocities is to look forward to a better world, to look forward to the situation, as if it has been already repaired, to look at what the best way to move on would be. That was very important in apartheid, South Africa and post apartheid South Africa and it was really something a lesson of humanism, that South Africa, then the South Africa of Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela taught the rest of the world.

So I think that today raised the amount of atrocities to us again, the only word that one can use even what the situation is, and given the amount of suffering and even the tribal nature of this this war. The only way to move forward is precisely to look for the humanism of Ubuntu and the wisdom of Ubuntu and say, why don’t we project ourselves in a future of peace? Look at what that future of peace looks like? And obviously, it has to be a future where both Palestinian people and Israelis are living in their own states and being fully citizens and not being occupied people for example, and look at that picture and look at the right actions that are going to lead us there. And this is the wisdom of Ubuntu. Deciding that at one point, the actions you have to take today should be dictated by the future that you need to go towards rather than the past because the past is just going to repeat itself otherwise.

CLAUDE:

There are many different definitions of Ubuntu. We talk about Ubuntu quite often, actually, surprisingly on this on this podcast. And the definition that I always use is not a literal translation but it’s a bit of an extrapolation, but it would be I am because you are or I cannot be free, unless you are free. Right and so it’s really the sense of community. And as somebody who was one of the world’s foremost scholars on Islam, do you think that there can actually be community in a place like Israel/Palestine, when culturally they are so divided by different religious affinities and sensibilities?

SOULEYMANE:

Yes, you are correct to saying that the semantic field of Ubuntu is quite rich. It means many different things. But, as Mandela famously said, once it means many different things, but ultimately it is about making the community better. And making the community building a community is really what Ubuntu is about. The idea I see two notions covered by the concept of Ubuntu: one is that humanity is not a state but a task. We, humanity is something we have to realise in ourselves. And the only way of achieving humanity is through somebody else achieving their humanity. That is what Ubuntu is about. Right. So it is precisely this concept that can make possible what seems impossible when you just look at the situation. When you look at the situation, yes, what you see is the huge divide between Israel and Palestine. And you are with Ubuntu, you are betting on something that is a shared humanity. The idea that on both sides, people want to live in peace, want to raise their children in peace, make sure that their children can have the best possible opportunities and that their rights as citizens are fully respected. If we look at those basic principles, we understand that they are shared by both sides. So yes, at this point, the the hatred – unfortunately, one has to call things by their name – is so deep that you cannot see how to go beyond it. But let’s remember that the last genocide of the 20th century, which happened on the African continent happening happened in Rwanda 1994 1994 Unfortunately, the first genocide also happen on our on the African continent, and this is where the genocide of the hero as we know, and the German rule of from Namibia, but let’s go back to what happened in Rwanda. Here you had neighbours, killing neighbours, neighbours, witnessing neighbours killing their own people.

CLAUDE:

Wole Soyinka actually wrote an essay, that’s what he said that actually, there were people men killing their own wives because they were Tutsi.

SOULEYMANE:

I mean, you cannot imagine how this could happen. How at one point, this tribal primal hatred between two communities could go as far as making someone killed their own wife. The mother of their children, because they don’t see in them the partners of a life, but someone belonging to a different ethnic group. And even in a situation like that is situation of genocide, a situation of massacre, they were able to try to move on to try some Ubuntu, to try some forgiveness.

CLAUDE:

You mentioned the divide between Israel and Palestine or Israelis and Palestinians. But do you also believe that there’s a divide between Jews and Muslims, because even you have written so much about the history and the philosophy of Islam, but historically, has there always been a divide? And in some cases, I can even call in hatred between Jews and Muslims.

SOULEYMANE:

Well you know, this kind of hatred of Jews, we have to remember that problems happen in Europe, and that the Holocaust happened in Europe. And we have to remember for example, if you want to look at historical examples, that when the so called Reconquista of Andalusia happened, when the Muslims were kicked out, they were kicked out with the Jews that lived also in Andalucia. So we do have in history, the testimony of the way in which about the way in which Jews and Muslims lived together, they live together in northern part of Africa, it was not always beautiful, wonderful etc, but you did not have the kind of pogroms you had in Europe, for example, and we have to avoid also translating in simplistic terms, in religious terms. What is happening in Israel/Palestine is a question of land, and a question of citizenship, and a question of right. So if we transform it into a kind of cosmic war between the cosmic entities that is the Jewish religion and the Muslim religion, we are going to miss the point and we are not going to reconcile them because you do not reconcile different metaphysics and even in that case, if you look – if you look at the content of the religions, religious dialogue, it would be then possible, but let’s just not forget that this is not a war of religions. It is primarily war about land that needs to be shared by two people in many different forms. Otherwise, you would you would have for example, right now you hear sometimes the right wing in Israel talking about de radicalization of the Palestinians. It is they are not fighting because they are radicalised. They are fighting because they are looking forward to having the rights to a state right. So that is very important. Now the religious dimension obviously cannot be just dismissed. And this is where religious dialogue is important. I belong I am with other friends. Working in a team we are working on something we call “the untranslatables of the three monotheistic religions”. And so we work on on red, let’s call it comparative religions, right. And that is something that needs to be done because the idea of humanity at peace with identities, with religions, actually demand that we look at those aspects as well. But we cannot flatten the conflict to the war on just religious issues.

CLAUDE:

You are an academic, you are at Columbia University in New York. And I was telling you that I’ve been teaching at Harvard for the past few years, Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. And when I was there in January, I witnessed something that was really surprising, which I’ve never seen, is a student who was actually originally from Egypt Muslim, was saying that the campus was so polarised that people weren’t talking about the Islamophobia on campus. They were only talking about anti semitism. But the Muslims on campus actually now feel even more ostracise than the Jewish students. And so everything is so polarised now. Do you think that there is a way to bring people together or is it just going to be increasingly polarised

SOULEYMANE:

hopefully we wouldn’t be able to get out of this, obviously, what happened, what you witnessed on the Harvard campus is something I have witnessed myself on Columbia campus with all the protests and counter protests that happen on the campus of Colombia, and both sides claiming to be the victims of bigotry and Islamophobia on the one hand, antisemitism on the other hand, and probably these, both were true, because unfortunately, in these kind of contracts, you have this radical I would even call it tribal. division where everybody’s feels that they are actually the victims. But this can be also measured that we do know that there were a certain number of anti semitic incidents during these protests. And that they were also Islamophobic incidents as well. And we have to acknowledge it and acknowledge that in the heat of the situation, unfortunately, antisemitism has rise beyond just go through the roof. And that Islamophobia also has been a reality. When it happens on campuses, it is really, really sad. I was thinking before I left, I travelled abroad, that probably students of mine, were on both sides. of the protests. And that made me really, really, really sad. I was sure that if I had stopped to look at who were protesting, I would have recognised students of mine on both sides and this is really painful. For on a campus and where we should have a sense of intellectual community, but hopefully it is going to happen. I am really optimistic and I do think that the level of atrocities we have been witnessing and we are still witnessing unfortunately, and the depths of the crisis is such that what is called international community is going to come together and try now its best to really solve this crisis.

CLAUDE:

One of the things that we talked about in our previous interview a few years ago, was the whole concept of ‘citizen of the world’, this concept of citizen of the world when I told you that one of my strengths what I would even call a superpower is my ability to as an native son of Togo, who’s also a French citizen. And who’s also an American citizen, navigate multiple worlds. So I’m constantly going back and forth between the Jewish world, the Muslim world, the white Catholic world, and the black community, which is really where I have pretty much spent my life and to go back to your concept of Ubuntu. Many of my black friends in America, in Europe in Africa, have said that they feel very much that Israel is just like South Africa in a sense of promoting a form of apartheid. And this crisis, you mentioned, Israel, Gaza has really driven a wedge, in some cases, and in many different situations between blacks and Jews. Is this something that you have observed as well?

SOULEYMANE:

Unfortunately, it is something real it is something that has to be observed. You have had some, I mean, when you mentioned a wedge that was created between the two communities, it is unfortunately, true. In a general way, the so-called progressive camp has been very much divided by this conflict. And people have found themselves on it in in an opposition to other people that they thought were on the same side on the same political side. And friendships have been really damaged by this conflict as well right. So this divide that you mentioned, which has to be acknowledged because it is it is real, in many, many cases, has to be acknowledged where when black people have very widely generally sided with the Palestinians and identified themselves with the Palestinians thinking that they are the oppressed, that they will Yes, exactly. They see they see them as oppressed. Just like they have seen themselves as the oppressed. So it is true. It is true that that divide exists, and it is something that really needs to be repaired, which is a very painful divide because let’s remember, the same way when he famously said: When you hear someone say something against a Jew, pay attention. They are speaking about you, you owning the black person, so that you can call it naturals that existed between a Jew is something that needs to be recreated or reinvented and that is an aspect. One of the very painful aspects of this Palestine war

CLAUDE:

absolutely many people remember how some of Martin Luther King’s allies were Jews back in the early days of the civil rights movement in America. And so unfortunately, times have changed. And the Black Lives Matter movement, perhaps has a different perspective on Zionism. But if we want to go back to your concept of Ubuntu, and think about it from a Pan African perspective, what role do you think Africa can play in helping to resolve this conflict, not just South Africa, but just Africa as a continent?

SOULEYMANE:

You know, there is something that people probably do not remember because it did not. It was an initiative that did not start seed even beginning. Back then in the 1970s. At one point, the President of Senegal Leopold Senghor, the very first President of Senegal, so that he could try to, you know, talk to both sides, Palestine and Israel. And that was very idealistic when you think about it, but the context at the time, was singers idea of the force and the power of dialogue. He was a philosopher of dialogue, and he believed in dialogue, and he had expressed admiration for Israel as a socialist state. He thought of the kibbutz culture for example, as a way of realising the socialist idea that he shared, and he also believed that being from the third world as it was called at the time and close to the Arab world, close to the Palestinian world he could really be a promoter of some form of dialogue. Now is inside we think, Okay, did he really? Was he really that naive thinking that tiny stage like Senegal could just decide to have some kind of huge geopolitical role. But the reason I’m mentioning this is that it is time to remember that to remember that a country that had little very little weight economically in the world, etc, had a leader who had a vision like that, and who saw that there was something in the in African humanism that could be put to work on a for a situation like that.

And I believe that now the situation the word has changed, and I believe that the voices of Africa if Africa speaks as one voice, Africa can have some geopolitical role in the configuration, the general configuration of the word and some geopolitical role in being an actor for change and active for that kind of humanistic role. That same goal was trying to play. I mentioned how Ubuntu has been not just to put to work in South Africa, it has been globalised. It is a universal concept of restorative justice and I believe that Africa has some legitimacy to say. We are a continent that has been victimised that has suffered but at the same time is also in has a history and a culture and spirituality. Meaning that we know something about humanism and shared humanity and we can try our best to speak the voice of humanity. Two sides like that, that are so divided that are so tribalized in a way that at one point they might need someone just calling the shared humanity upon which a solution can should be built.

CLAUDE:

Thank you so much for your time. Souleymane, it’s wonderful to interview here on the African continent in Marrakech and I look forward to seeing you again.

SOULEYMANE:

Thank you it would be a pleasure as always

CLAUDE:

If you enjoyed listening to my conversation with Souleymane Bachir Diagne, please rate and review this episode on Apple, Spotify or your preferred podcast platform. We need to promote measured and informed dialogue – so please share this episode with all your friends – email them, DM them, tweet at them. It’s the best way we can get the word about Limitless Africa out there.

Listen next

"Nigeria is hot with fast girls" - The sprinters going for Olympic Gold

With guests: Favour Ofili, Olayinka Olajide, Rosemary Chukwuma, Tiana Eyakpobeyan

LISTEN NOW 17 min

Can sport change women's lives?

With guests: Akoko Komlanvi, Alcinda Helena Panguana, Esti Olivier

LISTEN NOW 15 min