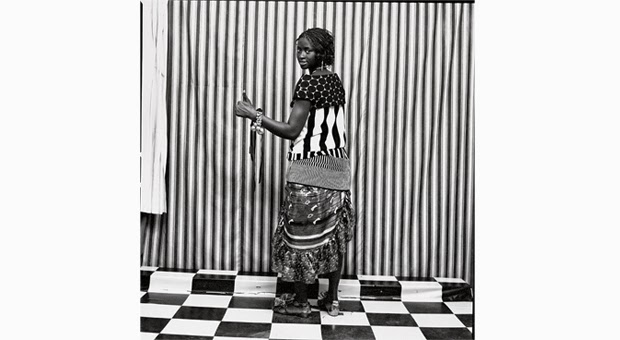

A tribute to the photographer Malick Sidibé by Awa Meité, a friend of the family and curator of his work.

Humanity – and I mean the happiness of others – was his priority. It nourished his art and gave meaning to his life.

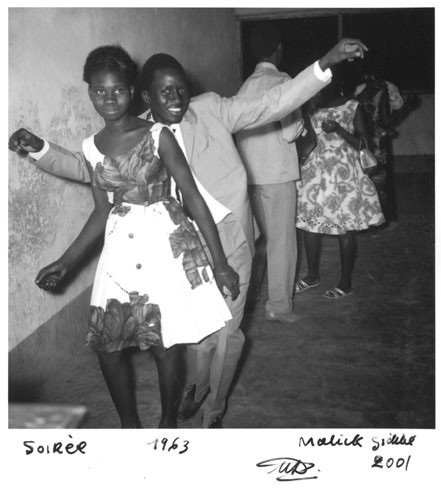

I’ve known Maliki – that’s what he’s called in Bamako – since forever. He was the photographer of my parents’ generation and he would immortalise surprise parties, days out at the beach, alongside the photos that became familiar across the world.

People from my generation, who grew up in Médina-Coura, all knew Maliki. He used to give us money to buy sweets. He used to sit in front of his studio, often with friends – that is if he wasn’t travelling the world, at conferences or exhibitions.

I knew a Malick who was patient and generous, whom immense fame would never change.

His passion was repairing and restoring old cameras. He never threw anything away, even when it wasn’t salvageable. He placed them like relics on a shelf. They were there, in pride of place, vestiges of the past, cloaked in dust and memory.

He treated his thousands of negatives with similar care, sorting them by year, in little yellow recycled boxes.

During the long holidays, when I came back to Bamako, Malick‘s studio was somewhere I would always go – part of the pack of little children who would pester him. But we would wait patiently if he was photographing a client or was finishing to install a very important piece on a camera. I knew a Malick who was patient and generous, whom immense fame would never change. We stopped seeing Malick and his family when they moved to the other side of the river and opened a new studio in Bagadagi.

After that, we only saw him on the television.

It was only many years later that I saw him again. Friends from Europe had told me that their dream was to meet Malick Sidibé and be photographed by him. So I looked for his studio again and re-established contact. I was even happier when I found out that my childhood friend Mody was his assistant. I often visited him during those last few years as if I wanted to get back all those years during which we hadn’t seen each other. He was often sitting, when his health permitted it, in his room where a section of the wall was decorated by a tapestry of those little dusty yellow boxes, in which thousands of negatives were stored.

He welcomed few people into his home because his family knew that he was tired and weak and wanted to protect him. The honour was never denied to me and even when friends visited and wanted to see him and show their admiration, Maliki was always welcoming and smiling. He had some incredible stories to tell. One could hardly hear his voice but his son Mody was always on hand to make his father’s words audible.

From Médine to Bagadadji, his home was a meeting place.

He was always incredibly lucid. In this moments we’d laugh uproariously. I would tease him affectionately. I would talk to him about projects that he was enthusiastic about and he would give me advice. In 2008, I curated the Malian pavilion at the Bienal de São Paulo with works by Abdoulaye Konaté, Seydou Keïta, and of course Malick Sidibé. It was his first exhibition in Brasil.

But what other honour could I give to the great Malick Sidibé, one which he hadn’t already received? But at his age, even a small gesture is important.

I had a deep desire to recognise Malick Sidibé in 2015 with the Daoulaba Festival I organised to celebrate the textile industry. I asked that Maliki be recognised officially. After the festival he was given a knighthood. A wonderful and final homage from Mali, a country that meant so much to him and for which he had done so much. In 2016 during Bamako Encounters I had the wonderful pleasure of seeing him smile like a child when he saw the exhibition I organised of his work .

Malick would say that he could only be happy if those around him were too.

For me, Malick Sidibé is one of the great men of the 21st century, whose work showed an Africa which was dignified and upright, on the same level as the rest of the world.

He was motivated by an incredible energy and an unshakable conviction in the African values of solidarity and sharing, values to which he stayed faithful till the end. Malick would say that he could only be happy if those around him were too.

Maliki helped entire villages, by buying barrows for farming for the men, installing pumps in villages for women, paying for schooling and giving money to help the sick. What he earned, he shared with everyone.

His work will continue to bring pleasure.