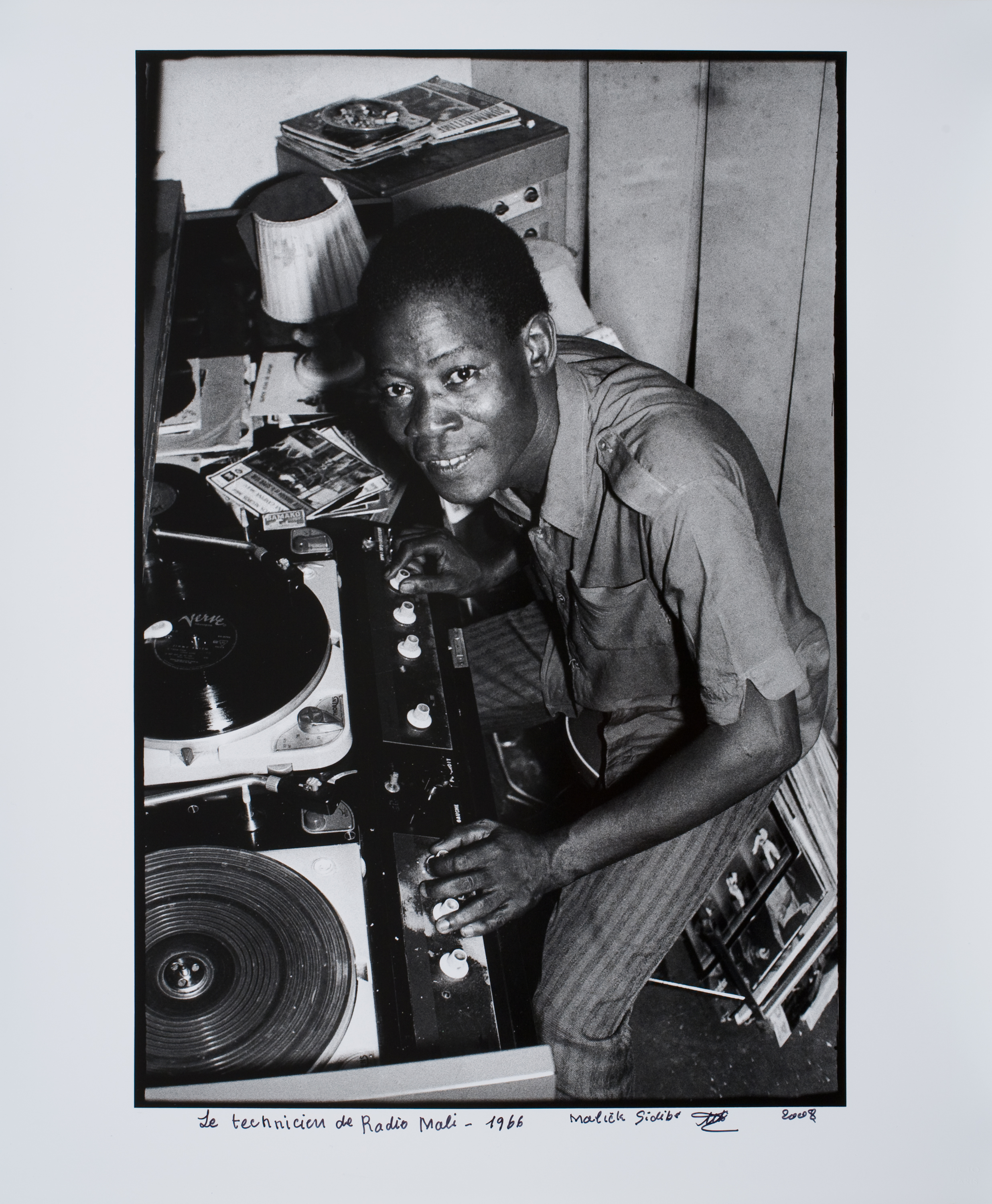

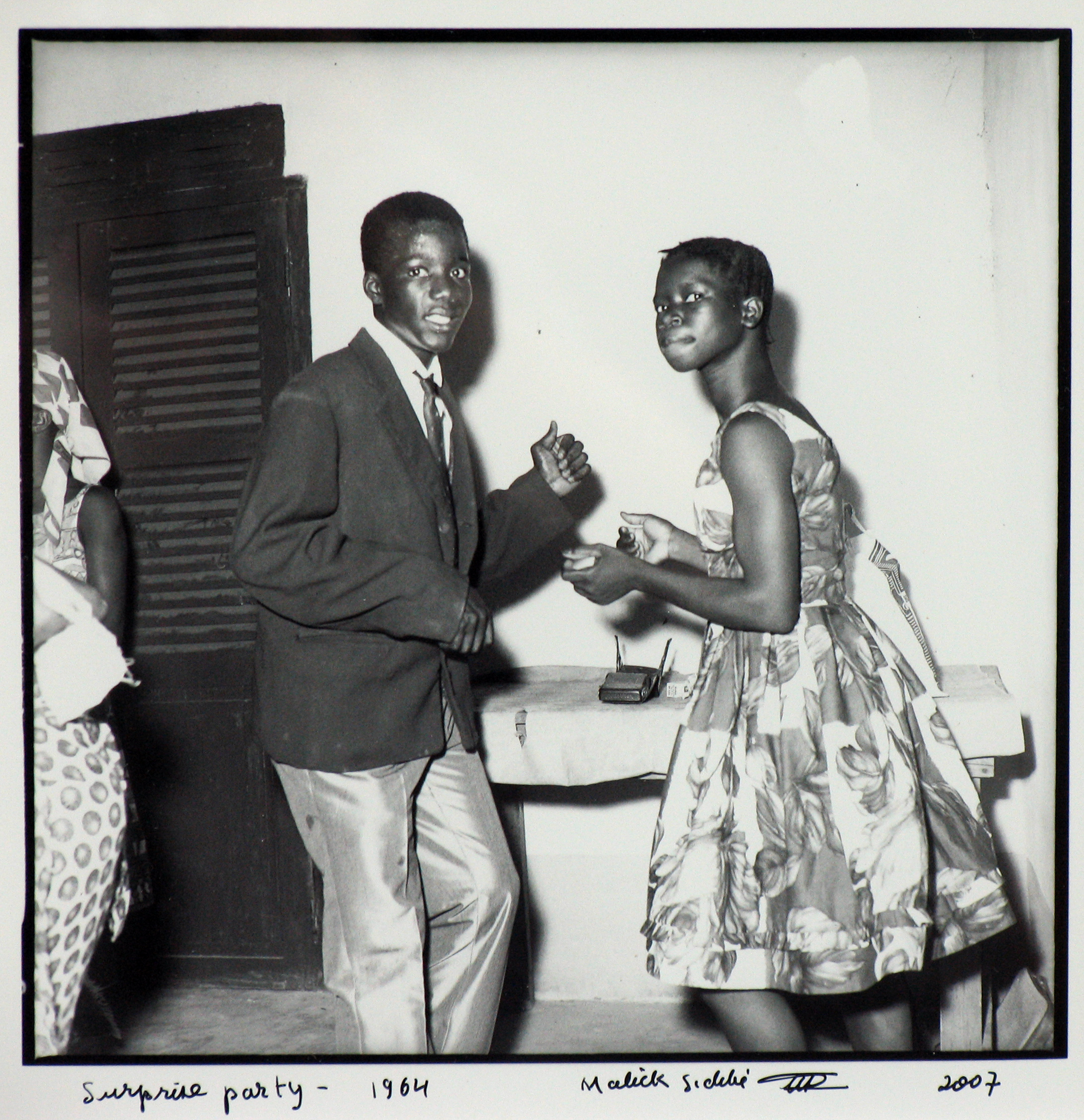

On April 14, 2012, four years to the day before Malick Sidibé died of complications of diabetes at age 80 in Bamako, I went to a reception at the agnès b. gallery in New York’s SoHo neighbourhood. The reception was in honour of an exhibition featuring a selection of Sidibé’s street and nightlife images from Bamako, during the 1960s and 1970s. The press release had announced that ‘Sidibé was the only photographer documenting this vibrant period before Mali’s independence from France in 1960 and his work gave birth to a new generation of photographers.’

I had been following Sidibé’s work since the mid-90s, because my ex-wife had been working as an assistant to André Magnin, the Paris-based curator and editor who made a living by collecting Sidibé’s work on behalf of the arts patron Jean Pigozzi. I just loved the way Sidibé seemed to catch people off guard, from the merengue dancers to the poseurs on the motorbike.

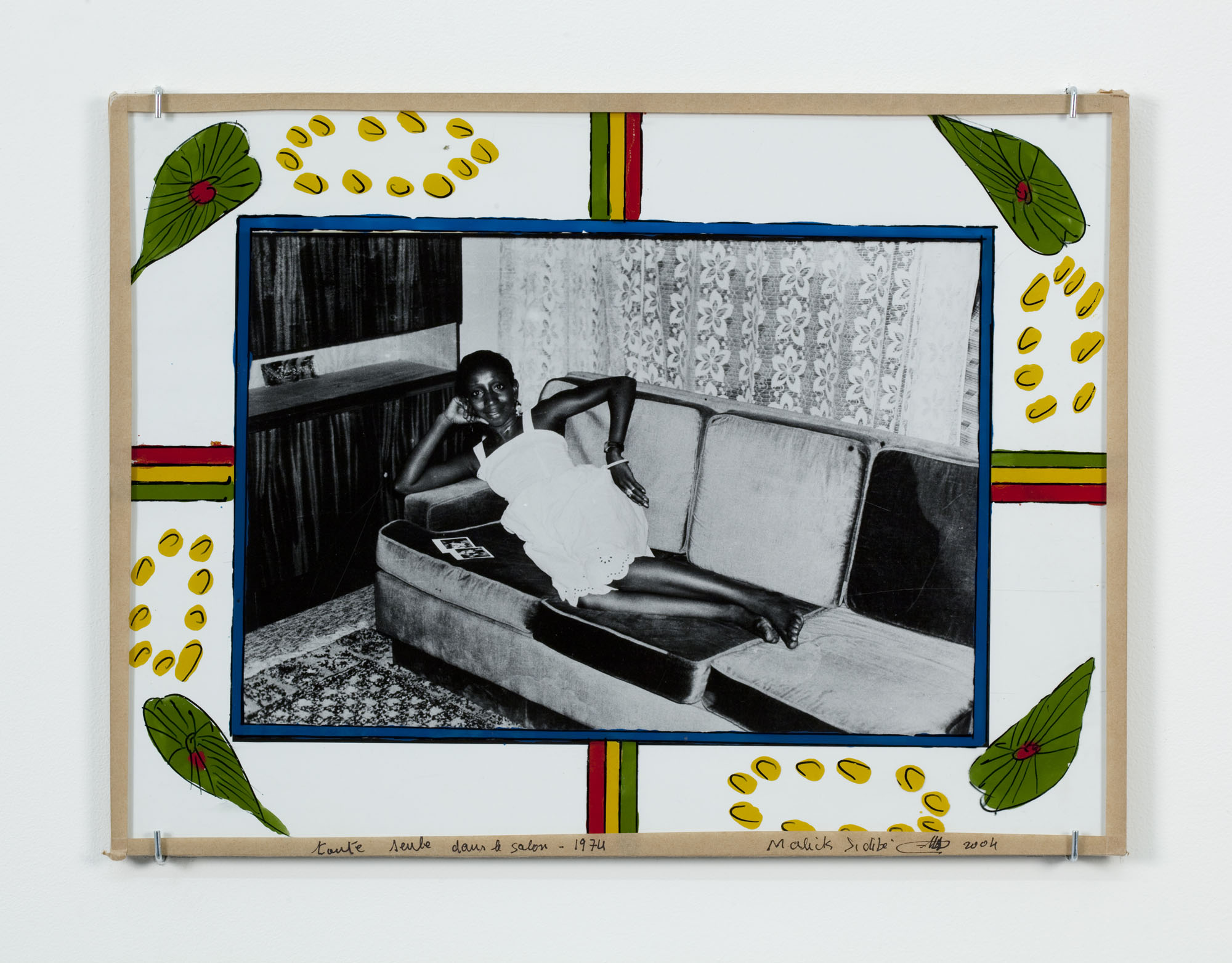

And even though his most famous studio photos were carefully constructed in order to, paradoxically, enhance the spontaneity of the moment, there was always something instantaneous about his images. I, too, began to collect Sidibé’s black-and-white gelatin silver prints, along with vintage black-and-white photographs by his older compatriot, the late Seydou Keïta.

He documented a society in transition, and the best pictures speak to the possibility of possibilities.

In a 2008 video interview, Jérôme Sother asked Sidibé about his time as an assistant (and part-time decorator) in Gérard Guillat’s studio. Guillat was a well-known Bamako-based French photographer who, in the mid-1950s, took Sidibé under his wing and encouraged the young man’s creative endeavours just as Sidibé was toying with the idea of becoming a photographer himself.

‘He didn’t teach me how to take photographs,’ Sidibé remembered. ‘But I watched him and I understood how to take photographs. I did the African events, the photos of Africans, and he did the European events—the major balls, official events. He did that. And I did the events for Africans. I knew of other European photographers who would not allow their employees to buy a camera. I was lucky, and from 1957 onwards I started to take photographs in town for the Africans.’

The body of work he produced, the thousands of Africans he photographed, at house parties, in dance halls, at weddings and christenings and even in his own studio, all those images ended up forming a valuable archive of post-Independence African optimism. These Africans were vulnerable, but they seemed to be going somewhere. More importantly, he documented a society in transition, and the best pictures speak to the possibility of possibilities. Sidibé was based in Bamako, but he could have been based in any West African capital. His work was transcultural, and universal.

There were many respected studio photographers, operating in Bamako, Dakar, Conakry, Abidjan, even in Lomé where I was born, but few were able to step out, to venture into the night with a small, flash-equipped camera. Because most of the established African photographers were confined to their downtown studios, with their impressive plate cameras and wooded stools, Sidibé stood out because he consistently found—and captured—excitement when others were happy to make the locals (any local) look beautiful.

And that may be his greatest achievement, living to tell the tale of everyday Africans who were trying to find their way in the post-colonial age. The people in his photos were alive, they seemed happy to be photographed, and one could sense their pride in their new African identity. They were well dressed, sometimes overdressed, but they were never inert. Many of Sidibé’s late night photographs seemed to freeze the frame right before the subject was ready to take her clothes off, to let loose at dawn, to let her guard down.

I spend a lot of time thinking about how Africa is perceived, how we Africans are portrayed in Africa, and in the outside world. Last year, I was drawn into yet another conversation about Africa-focused journalism. Howard French, an African American former New York Times correspondent in Africa who is now an associate professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, went on TV and started a series of controversial blog posts about the Western media’s coverage of Africa.

Here was an African documenting Africans in Africa, for the world to see.

He mentioned that ‘there’s a large literature of what’s meant by Africa without Africans.’ He wrote about journalism that quotes ‘just diplomats plus aid workers plus foreign experts of one kind of another.’ Usually, he wrote, ‘they’ll throw in a quote from a taxi driver or an anonymous market worker.’ The Howard French debate on the web turned into an exchange of arguments about why Africans now need to tell their own stories, in order to reclaim their African identities.

This all happened while we were planning the launch of TRUE Africa. Obviously, that debate informed our ‘Made in Africa’ approach to storytelling. Our African media platform was going to be about ‘the future now’ and new African voices, and new African identities. I remember thinking that Africans have been telling their own stories for centuries, but those stories weren’t getting the sort of traction or real estate they deserved.

Soon after we launched TRUE Africa, we realised that, in the way our stories were being consumed in the fast-paced digital age, images were becoming just as important as the words, and as we experimented with photography, a lifelong passion of mine, I searched through the web and looked for images that somehow managed to grasp the complexity of African identity.

And, since I have spent my entire career promoting black portraiture and black imagery, any debate about the way we are seen and portrayed now was going to be useful. I have always believed in publishing strong images that document modern lifestyles while observing the imperative of going beyond established boundaries. Within that context of exploration, the timeless black-and-white photographs created by Malick Sidibé became even more relevant as a reference point. Here was an African documenting Africans in Africa, for the world to see.

Sidibé was very prolific, and he kept working in his Bamako studio until a few months ago. Even after he became world famous, showing his work in the biggest art galleries in New York, Paris, London, Tokyo, and winning all kinds of prestigious photography prizes all over the world. Those who knew him well kept speaking of his humility and continued zest for life and discovery. The Bamako-based fashion designer Ama Meité van Til, is a close friend of the Sidibés. When I interviewed her last month in Bamako, I found out that she had been working with Sidibé’s children on planning a touring exhibition of his work. There was huge demand for his prints, all over the world.

I remember the time, about a decade ago, when the height of cool in Paris art chic was the ability to travel to Mali in order to sit for a Sidibé portrait, right in the famous Bamako studio. From the designer Philippe Starck in Paris, all the way to my cousin Marie-Cécile Zinsou in Cotonou, everyone wanted to be immortalised by the master.

In the coming years, when a new generation of street photographers and digital image-makers comes to think of the influence of Malick Sidibé, who rose from humble origins in provincial Mali to gain global visibility for his work, I hope they will make an effort to understand the quest at the centre of his creative process. Malick Sidibé has gifted us with a huge legacy, and any discussion around the merits of his photographic archives should consider that his strongest center of value might be the way he was able to capture all kinds of Africans—and non Africans—in their most authentic states.

Images courtesy of the Jack Shainman Gallery