"Women bring a subversive perspective" - Author Novuyo Rosa Tshuma on Zimbabwean literature

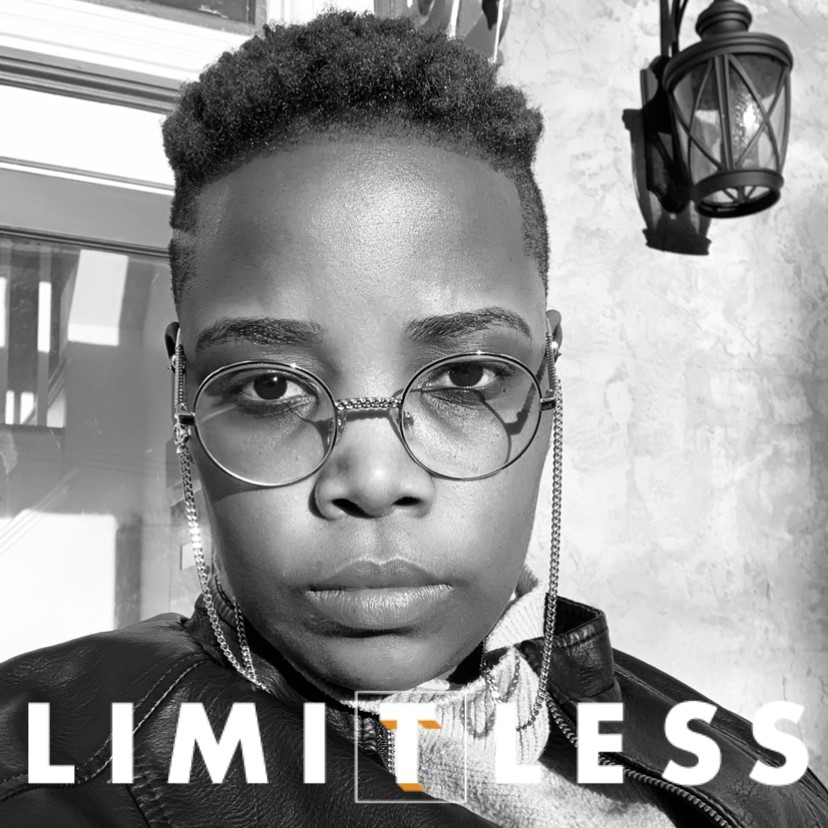

With guests Novuyo Rosa Tshuma

Episode notes

The award-winning novelist who teaches at the Iowa Writers Workshop

Transcript

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma is an award-winning Zimbabwean novelist who teaches at the acclaimed Iowa Writers Workshop in the US. And she’s only 36 years old.

Her debut novel House of Stone is set during the Gukahurundi massacres that took place immediately after Zimbabwean independence and remain shrouded in secrecy. Her second novel Digging Stars deals with an equally uncomfortable histo...

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma is an award-winning Zimbabwean novelist who teaches at the acclaimed Iowa Writers Workshop in the US. And she’s only 36 years old.

Her debut novel House of Stone is set during the Gukahurundi massacres that took place immediately after Zimbabwean independence and remain shrouded in secrecy. Her second novel Digging Stars deals with an equally uncomfortable history. She charts the similarities between the reserves allocated to native Americans in the US and those allocated to indigenous people in South Africa and Zimbabwe.

This is a must-listen for anyone interested in African fiction. Novuyo gives us a peek behind the scenes of some of the US’s most prestigious writing institutions and tells us what it’s like to be a young African professor there.

Please listen to a previous episode: Does Black Lives Matter matter to Africa?

And let us know what you think here.

Transcipt

CLAUDE

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma is an award-winning Zimbabwean novelist who teaches at the acclaimed Iowa Writers Workshop in the US, like many literary icons before her. And she’s only 36 years old.

Her debut novel House of Stone is set during the Gukahurundi massacres that took place immediately after Zimbabwean independence and remain shrouded in secrecy. Her second novel Digging Stars also received glowing reviews. It deals with an equally uncomfortable history. She charts the similarities between the reserves allocated to native Americans in the US and those allocated to indigenous people in South Africa and Zimbabwe.

This is a must listen for anyone interested in African fiction, interested in reading it of course but also interested in how it is produced. Novuyo gives us a peek behind the scenes of some of the US’s most prestigious writing institutions. And tells us what it’s like to be a young African woman professor there. She’s equally clear-sighted about the situation in Zimbabwe and what it’s like to come back home with your partner when you are queer.

It’s a wonderful conversation, I hope you enjoy it.

CLAUDE

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma. Welcome to limitless Africa.

NOVUYO

Thank you, Claude. It’s such a pleasure and honoured to be talking to you today.

CLAUDE

Well, the pleasure and the honour is mine. Because when we talk about critically acclaimed writers, it doesn’t come much better than yours. I mean, your novels are critically acclaimed. They’ve had glowing reviews in the New York Times, The Guardian in the UK, all kinds of publications praising you so let’s start with you and who you are. So tell us about yourself.

NOVUYO

Thank you, Claude. Well, first and foremost, I’m a reader. I’ve always been curious. I’ve always loved books ever since I was a child and it’s something I learned from my father. You know, he gave me a love for reading. And from there ballooned the love for writing. So the two are intertwined. I’m always reading across genres across disciplines. And so that’s what fuels my writing and my curiosity about the world. I’m also an immigrant, moving the USA for the past 10 years, and I’m originally from Zimbabwe spent the first 20 years of my life. I’m also an academic and an educator. I teach creative writing and Emerson College in Boston, I’m also faculty director of the James Baldwin summer programme is a programme that Emmersons runs each year and takes place in Paris and that’s the opportunity to take our students, mostly from underrepresented backgrounds abroad, to learn about James Baldwin’s life, and his work in fiction and nonfiction and how it might inspire them to think broadly and engage with the world and be aware.

CLAUDE

One thing I wanted to ask you about in your illustrious background is your experience in the MFA in creative writing from the Iowa Writers Workshop, it’s very prestigious. I’ve heard so many tales about that programme, where literally the day you arrive, you have different agents and publishers lining up to sign you up as an author. Tell us about that experience. Because it must have been a formative one.

NOVUYO

It was very formative. I got the call about being admitted into Iowa in Cape Town, and I can’t explain at the time it was 2012, it was early 2013. The MFA hadn’t really exploded globally. I would say I really didn’t know much about MFA programmes. I’ve been in touch with the writer NoViolet Bulawayo who inspired me to apply for this programme. So I really did not know what I was, except they were giving me a full scholarship to go there.

CLAUDE

And full scholarship we like that sounds very much like free.

NOVUYO

I mean, it was really incredible when I got there. I think I love being the space surrounded by people who love to write who love books. It was just an everyday staple over coffee over drinks with friends. We were always talking about writing in books. I also appreciated the global nature of the programme. Some great friends there, from India, from Jamaica, and also a lot of black American writers and writers of colour and this speaks to the current director Sam Chang, Len Samantha Chang, who’s Chinese American, and her efforts to diversify the programme. And yes, agents do visit the programme. I met my agents there. So that’s part of the I guess the prestige of the programme because it’s known for his writing.

CLAUDE:

And you’ve actually gotten back there to teach fiction right. Tell us about going back.

NOVUYO

It was really an honour for me to have the workshop invite me to come and teach. I think it for me it spoke to my growth as a writer. And the work I’ve done there and the work I could do there, mentoring students and it’s one of my most profound experiences as a teacher. The students there are very energetic, outspoken and gregarious. So it was also interesting to sit on the other side and sort of understand how the classroom works from a professor’s standpoint.

CLAUDE:

In terms of sitting on the other side, you describe yourself as a reader, but also you’re a writer, and you’re also a professor. Why did you feel that it was important to become a professor and to get your PhD in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Houston?

NOVUYO

Oh the University of Houston. That’s another great programme in the USA. It’s one of the top PhD Creative Writing programmes in the USA. I wanted to expand my intellectual horizons, Claude. I think it also comes from just again my father as an inspiration. My father was a lawyer, but he was also a doctor. Doctor Tshuma, Doctor philosophy, someone who loved knowledge and education and really wanted to reach as high as I could go, but I think it’s also very African thing. I was gonna say that we Zimbabweans…

CLAUDE

Africans, we can never get enough education, right.

NOVUYO

Zimbabweans and Nigerians are famous for just having PhDs PhDs, but that really opened my eyes to the importance of teaching, right, and not just teaching fiction, the craft of fiction but art is also a way to think together to build empathy, diversity, right? I think the humanities are really good at that and cultivating stewardship, citizenship, and that’s really what I’m interested in in the classroom.

CLAUDE

Right, in the classroom, and then life as well. I want to talk a little bit about life and being an author, being a novelist, and specifically your first novel House of Stone. And in that book, you kind of dug into the history of the Gukurahundi. Can you tell us a little bit about the book and perhaps help us to understand that history for those of us, and those of us listeners who don’t actually know the history?

NOVUYO

House of stone, oh Claude.,

CLAUDE

Let’s take it all the way back there.

NOVUYO

I started writing House of Stone or thinking about House of Stone, I was 23 I was really young. But I was so hungry for my history. And I was in South Africa. I was a student there and feeling unwelcome.

You know, once I’d learnt how to become Zimbabwe in South Africa because there was this constant fascination with Zimbabwe as a crumbling nation. And we became really flattened as a people and I really began to wonder, how did we come to be? Why is Zimbabwe the way it is? And as I read up on the history, I realised I do not know my country’s history, and there’s some pleasure to see yourself, to see your past, to understand yourself.

Now Gukaruhundi became the focal point of the novel. Because when I asked my mother about it, you know I’d ask about the Civil War, and she would speak lightly about it. We don’t really talk about history in Zimbabwe even among families. When I mentioned Gukaruhundi I remember she froze and I thought there’s a wound, there is something there.

And growing up we were never really encouraged or allowed to talk about these massacres that took place in Matebelland and Midlands part of the country right after independence in the mid 1980s. They were state sponsored massacres, state sponsored genocide. But because we don’t really know much about the time, the documents, the government documents about the time are sealed. It has been manipulated or cast as Shona VS Ndebele as an ethnic conflict and that’s been one of the most damaging aspects of it. Growing up I learnt that was what Gukaruhundi was about. Reading the archives and understanding the world of politics, I saw it as Zimbabwe’s first sin.

This was when Mugabe, our ex-president and our oldest president in Africa and world history started persecuting political dissidents, those who have different views, right. The understanding is because Matebeleland and Midlands had not voted for the ruling Zanu PF party in the 1980s elections, they were being punished for that.

The massacres are horrible when you read the transcripts. They speak of torture, starvation, families being forced to kill their family members, bury them, dance on their graves, it’s really atrocious. What’s really horrible is that there’s been no reckoning with that. The victims have gone unacknowledged. They did not receive any help, any social… and I’m thinking of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa as a comparison. So we have a lot of wounds. So that’s really what I wanted to sit with. And make sense of and try and understand.

CLAUDE

Well, it’s interesting that this history was taking place immediately after the late President Mugabe that you just mentioned was being hailed as one of the freedom fighters of Africa. I mean, Bob Marley released that album Zimbabwe that we will remember right as a tribute to that fight that was led by Mugabe and others. And I often think about how so many of us Africans just don’t know very much about our own history, even the recent history, the post-independence history. Why did you decide to focus on that specific history as it pertains to your country?

NOVUYO

I think it has to do with the fact that you felt like something that’s repressed, a wound that repressed and for me that links to all other wounds. For me the tactics that were used in Gukaruhundi, if you read up on it, some of them were used during our war for independence. And some of those tactics were later used in the 2000s when Zanu PF was repressing citizens, Operation Murambatsvina, Operation Clean up the rubbish where opposition party supporters in the 2000s had their homes bulldozed, right. That’s a mechanism that was also used in 1980, so it felt like a central sort of wound for me that could help us understand other wounds. And in Africa, history is not easy to talk about, it’s traumatic. I remember during my writing of House of Stone, I went to therapy, and I took the book for therapy, I needed to also make sense and work through what excavation this issue was doing to me, to my psyche, to my body, my emotions.

I think we also underestimate just how difficult it is to talk about this history and work through it. We need structures, we need state support. It cannot just be people looking through history. We need help as to how to look at that history and how to heal from that history.

CLAUDE:

That’s what I wanted to ask you about. I was going to interrupt you to ask you specifically about history. One thing that I read in The Guardian review, which again was a rave review, was that you went back into the history of your country and taking it all the way back to the arrival of Cecil Rhodes. And then kind of going into the history of the Ndebele Royals and so on. How were you able to do this sort of research when there’s not that much archival material that’s really available in print?

NOVUYO

So this was interesting. This is where is where the South African University of Witwatersrand library and the university of Iowa library. And the US libraries became so invaluable. I can’t tell you how many books I was shocked to delighted to discover in those archives that are not available in Zimbabwe. We have historians like Terence Ranger. We have novels from the period. For Gukaruhundi, there’s a book by Elinor Sisulu which is based on the Catholic Commission reports on the massacres, which happened about a decade after the massacres in the 1980s to find out what happened and speak up for the victims and of course that never happened. So there was that aspect again. There was also talking to family, talking to people. My family was… Oral history was a great depository of knowledge. At one point I wanted to go and see the graves in Balagwe in Zimbabwe. This was during a trip home and I was warned not to go there. So I did not go there.

CLAUDE

Why did people warn you not to go there?

NOVUYO

You know you will disappear. Like you’re causing trouble. You can’t go to the village and start asking these sorts of questions without causing trouble. Many activists in Zimbabwe have, you know, disappeared or paid the price. But for me the structure of House of Stone mirrors exactly what you’re talking about… the difficulty of excavating history.

Zamani, the main character who’s obsessed with history, becomes very sociopathic in his quest for history. You see the difficulty of just finding that history whether from talking to people and trying to get them to relive very painful moments or the archives which really don’t provide much access. This for me is why fiction became a very important way to talk about history, because there’s also the fact of imagination to imagine oneself into various moments as a way to get to a closer sort of human truth. about what that experience was like for the people who lived it.

CLAUDE

I want to maybe segueway a little bit and talk about your other novel, which I haven’t read, which is Digging Stars. And that book is really about the global nature of colonisation. And then kind of looking at, you know, certain histories that that again, you were able to uncover. Can you tell us a little bit about that book?

NOVUYO

Yes. It seems as a running theme in my novels, connections between histories and peoples. Digging Stars started off as an attempt to understand America. But my main character Athandwa was Zimbabwean. And so that became really key to me. So to understand who is speaking, right, who’s this person who’s speaking about America? And at first it was an immigrant novel, right and the immigrant novel is a trope… until I came across this history, about the connections between the North American reservations and our tribal homelands, what we call Amareserva in Zimbabwe. It actually came from a book from Mahmood Mamdani called Neither settler nor native, and he says he was in South Africa, researching apartheid. And he was interested in this connection between the South African Reserve and the North American reservations. Like why are the names similar? When he discovered that in 1910, the apartheid government sent delegates to Canada in the USA to study the North American reservation. They liked what they saw, and they brought back that model to South Africa.

And I said, Wait a minute, growing up you always hear amareserve amaserve in Zimbabwe – How come we have never actually made this connection? Then I went into the archives and you see that the British Parliament, the UK Parliament proceedings round about the 1920s, when they’re talking about Rhodesia, they were speaking about this model in South Africa. Right. That South Africa had bought from the US and they used that to model the native land acts in Zimbabwe and suddenly, that history connected us. And it’s this idea of creating taking a piece of land, usually very non arable and squeezing the indigenous people onto that land. Suddenly for me, American history came alive. And my first question was, how come we do not know this history in Zimbabwe? How come we don’t talk about this connection? We don’t really learn much about Native Americans in Zimbabwe or even as a country or as a people we’re trying to decolonize, we’re trying to reclaim our past, this seems really important. So that became my entry into the novel.

And so the novel became really about colonisation even in the modern sense. You know, the writer Tsitsi Dangaremba visited Emerson College last year. She said something interesting, she said, Britain was an external coloniser, and she has cast Zanu PF as an internal coloniser. This is our ideas of the values and morals that we carry in our society. Structurally, we actually come from the Rhodesian states, if you notice our country structures, including customary law, which is actually not native but was created by the British administration to manage the indigenous population. Little of that has changed in Zimbabwe. And so that for me became that exploration.

And so when Athandwa goes to the US to do something I haven’t seen any other immigrant novel, she interacts with indigenous characters and that’s for me, is the push and pull where these characters are struggling through this history. Struggling to understand one another, alienated from one another.

CLAUDE

When I was reading the New York Times review that came out in September of 2023. The review said that the story opens with Athandwa, who you just mentioned, and her father Frank who are reunited for the first time in New York City, and even though they’re from Zimbabwe, you start with New York City. Why choose New York City of all places as the beginning and the opening of the story? I say that because I live in New York City and I consider myself a Togolese New Yorker!

NOVUYO

That leads into one of the themes of the novel which is astronomy, indigenous science. So indigeneity for me, sciencitific knowledge was as a part of this novel, it’s key to understand the novel.

My characters were grappling and excited with knowledge of the stars, science and what it means to practice it in a contemporary sense. So Frank is in New York, because he is a professor of astronomy, and he becomes Atombe’s link in the field of science and astronomy. And in that first part of the novel, we follow his history and you learn about how he grew up in amareserva, in the rural homelands, watching the stars stargazing before he went to Mission School, and was getting a scholarship to go to the US right? And so for me, this is the nature, just the progression of how indigenous knowledge becomes co-opted into mainstream knowledge, but it’s also just about exchange of knowledge and human cultures. Franks’ experiences change him, and he grappled with what it means to practice science as an indigenous person. He’s also very controversial figure, but you have to read the novel to be able to find that out his lineage.

I’m interested in America as the centre of knowledge, because when we think of space, just say space, space exploration, what comes to mind? It’s America, and from public films and literature to NASA, you know, I follow the NASA Space Station on Instagram, they just always update on what’s going on in the stars and we think of the future we think of America, America also because again, it’s a global space that also imports its technologies, including settler technology, it was important for me that the novel start in the centre right the heart of empire, so that we understand how knowledge gets diffused from Empire, also gets absorbed by Empire.

CLAUDE

Very interesting how you talk about empire in this very new way, right? Because when people think of empire as it relates to Zimbabwe or Africa, you know, they really think of the United Kingdom. But in your case, I want to take it back to Yes, right. So, you know, it’s interesting because I heard you mentioned Tsitsi Dangaremba, who is a very prominent Zimbabwe, born author and you know, there’s no Noviolet Bulawayo, there’s a few of you, rising stars or established stars and on the literary scene who are women from Zimbabwe. Why do you think you and your peers I’ll call it are having so much success at the moment?

NOVUYO

Oh, great question. I mean, this is this is a wonderful landmark moment. The writer Tsitsi Dangarmeba speaks about how her landmark book Nervous Conditions was disparaged ignored in the 80s when she first wrote it, I think it took eight years for her to publish it from the time she wrote it. She really struggled with that book. And I think that was an era where someone was male writers were sort of taking centre stage. So I think it’s really great that right now the women writers join this public moment, also just has to do with the ways in which we are telling the stories that we are telling. There’s a lot of breadth and depth and nuance, I think in sort of the woman’s perspective the female perspective, these female stories that were previously considered unimportant in a male dominated field, right, we’ll talk about the era of Chinua Achebe, and Wole, all these greats, and suddenly the understanding that women can actually bring unforeseen, subtle, a subversive perspective, right, because of their position in society. And you know, and I also don’t want to essentialise women because in House of Stone the character Zamani the main character is a man is actually a young man. He was written by me. But I think it just speaks to the creativity… If you read Noviolet, Bulawayo’s latest book, Glory, it is a romp. It is insane, just the level of craft and creativity, the talking animals. If you read Tsitsi Dangaremba‘s This Mournale Body again, you have this Kafkaesque writing that’s been mined. You have new up and coming brilliant Zim writers, Yvette Lisa Ndlovu, who’s into fantasy and horror. She is working on a fantasy novel on Great Zimbabwe and I look forward to that. women writers we are we are not afraid to experiment to break the mould…

CLAUDE

Yeah, breaking the mould is something that I’m seeing a lot. And I often talk about it with my friend Kudzanai Churai who is going to be at the Venice Biennale of this year as a visual artist. And here in the United States we have people like the Danai Guira. A lot of people don’t know that she’s actually originally from Zimbabwe, even though she was born in Iowa, that we just mentioned right? And she’s the Black Panther and the Black Panther series. So very interesting, this creative scene that not just in literature, but also in other creative spheres. So that’s to me is really fascinating. Do you feel this as well or is it just me and my journalistic eye?

NOVUYO

Oh, definitely, I feel it. I feel it is exciting to see Zimbabwe… I love that you mentioned Danai… Any Zimbabwean who hears that name would recognise a fellow sister. But it’s exciting because we have seen what this diversity has done for you know a country like Nigeria. I think it’s it’s quite remarkable that Zimbabwe with our 16 million citizens we’re really tiny, are able to produce so much art, so much beauty, so much creativity – we’re quite prolific for our size. And so this also feeds into other creatives right? You see what others are doing, you gain ideas, you get to see what’s possible in terms of art and creativity. You know, what’s really hard at the moment and what I wish we could do more is give back.

Zimbabwe as landscape is really tricky right now in terms of the arts and what’s possible. The idea of what can all these creatives do together, what can we do to cultivate the arts at home is something I’m grappling with, right?

CLAUDE

But you have publications. There’s a lot there that is not necessarily exported, but there’s a thriving creative scene in Zimbabwe, right with publications that are you know, maybe not so why didn’t you get it but are still extremely influential.

NOVUYO

When you go to somewhere like Zimbabwe, the creatives there talk about that. This idea of an industry of distribution. I mean, Weavers Press recently shut down that;s one of our great independent presses that has done so much for the creative arts in Zimbabwe, and they simply couldn’t sustain themselves.

CLAUDE

I don’t even know that. That’s so sad.

NOVUYO

I am thinking of Nigeria as a scene where they’ve somehow managed to build a local industry, right you have Masove Books, these independent publishers, they’re all publishing locally. Even books that are published overseas and bringing them – that’s what Weaver Press did. SO in Zimbabwe, I guess my thing is how can we get people to stay rather than leave.

We have the Writers international network of Zimbabwe run by Iven Pretoria which is doing great work right. Now because of all this globally, I think because creaives also see what’s happening in the global north, there’s always a question and a hunger about what can be done in the global south to also build and show up those structures. So that creatives are able in some way or other to sustain themselves. Not even just financial, just in terms of just intellectual or personal, creative satisfaction if that makes sense.

CLAUDE

As somebody who’s been a key player in this field for quite a few years. Now. I want to say that what I’ve learned is the importance of collaboration, cooperation, knowledge transfer, paying it forward between Africans in the diaspora and Africans living on the continent. We mention Nigerians, and they’re very good at that, right. They have these links between Lagos and all kinds of cities in America and also in the UK, which are quite powerful and allow for great expansion of creativity in my field.

So yeah. I wanted to perhaps ask you a little bit about your own path to the US. Danai Guiria, because I mentioned her, her parents, as many African parents came as academics to the US. I think they were settled in Wisconsin before before Iowa. What about you, how would you were able to come to America?

NOVUYO

Oh, so I came in scholarship. So I got into Iowa

CLAUDE

SO that was the first scholarship that you mentioned earlier. That was your first. Yeah, okay. It’s

NOVUYO

So I was studying economics in South Africa.but I wanted to follow writing as a career path, as a vocation. And so I applied and I came here through privileged means, through school through academia, and I stayed, I did my MFA, did my PhD, and was fortunate to get a job as a professor at Emerson College. And so it moved from just coming to school to suddenly you’re building a life here, right? Suddenly you’re building community, it’s been 10 years and you realise that you;re settling here? It can be quite shocking, to realise that.

CLAUDE

Right. I missed that. I thought for some reason that you had had some sort of experience with United States before you came to America to the Iowa Writers Workshop.

NOVUYO

No, my father lived in Rome, Italy, as a lawyer. My mother has always been in Zimbabwe.

CLAUDE

So yeah. So let me ask you about the community that you first kind of encountered when you moved to Iowa was there in the broader United States, any sort of Zimbabwe community that you can lean on? We’re not really even interested in that given the diversity that you saw on campus, as you mentioned earlier?

NOVUYO

There were few Zimabweans in Iowa.

CLAUDE

in Iowa, few black people in Africa. Few black people in Iowa I would even say

NOVUYO

Exactly, I mean, most most Africans anywhere you go here in the US, are mostly from West Africa. So so I’m actually have more I guess, relationships with, like with West African communities, with the Nigerian communities, but I would say, Houston has a thriving Zim community there. That was really wonderful for me. We had celebrations, Independence Day celebrations, regular get togethers in Zim network. And in Boston, I moved to Boston during COVID. So my first time encountering others Zimbabweans was actually at a play, a Miriam Makeba play and it was so wonderful to see many of us there and so that that country bloomed for me from there, but I will be honest, I move I move through eclectic communities here and I think just has to do with my work as a creative. So just a lot of black community black American communities, of colour community communities, and of course, the white communities here, because those are sort of the main writing communities in the US. So I think I dip in and dip out a lot of these. I’m also loner by nature, I just want to say I’m a hermit that child has always seen the book rather than, you know, talking with others. So that’s probably also influenced that.

CLAUDE

I’m interested because I’m one of the things you and I have in common is I also go to Boston quite often because I’ve been teaching at Harvard for the past eight years. I’m actually going there again next week to teach and I’m wondering your experience teaching in Boston at Emerson College. There’s so much diversity in your students. Can they actually relate to your African experience? Is that something that you discuss with them? Or is it just kind of like a clinical kind of teaching style that is not so much dependent on your own Zimbabwe slash African experience?

NOVUYO

That’s a great question. Because we’re talking here creative writing? We’re talking about art, so one brings themselves into the space. I know for some of my students, I’m the first for one, I’m the first black woman professor that… the first black professor, the first black woman professor, the first African that they’re encountering particularly the undergrads. So first day of class I introduced myself and I give my history where I’m from, what I do, and throughout my syllabus, right I make sure I always assigned diverse works, including works from the continent. Because it’s a creative writing class, inevitably, the students bring themselves and we have conversations around differences.

It’s one of the key things happening in academia right now but also in the United States. So for me the classroom is a microcosm of what’s happening in the society. And I think my students, they more or less fare well with it. Perhaps because it’s a controlled and curated space. I won’t say there haven’t been awkward moments, but for me, that’s part of the work of difference. Slip on the tongue. I’ve had an interesting question the other day, one students said to me, this was during break like, oh, English is your second language, right? I just wonder where that question came from. Well, it’s my first language. We were colonised by the British. That was with my own language. And you see this surprise. I think there’s also these projections that me and the students have to work through together throughout the semester in the classroom.

But it’s just part of the work. That’s just part of the work we do as creatives. I’ll say one of the most difficult things for me. I’m also a young professor, I’m 36. It’s also has to do with how to establish authority in the classroom. I guess that’s something again I’m aware of as just a young professor who’s not from this country. One is perhaps questioned more than perhaps say your white male older professor, but it’s good talking to my colleagues, they say they did have some experiences when they were younger. And we have a great community in Emerson faculty, women, a women’s group, women faculty, black faculty, so we meet regularly to talk about the struggles we face in the classroom and have strategies to deal with it. So I really appreciated that sort of support.

CLAUDE

I wanted to ask you, if your students are actually able to locate Zimbabwe on the map or even know where Zimbabwe is. And the reason I ask that is because my first year teaching, I was surprised that most of my American students had no idea where Togo was and I didn’t, you know, judge them as a result of that lack of knowledge, because Togo is a very small country. But Zimbabwe is a country that is mentioned in the news more than Togo say so do you think your students know where Zimbabwe is?

NOVUYO

You will be surprised to know they don’t know. They don’t knowwho Mugabe is. Theyy don’t knwo where Zimbabwe is. It’s not even in their locus. Yes. I wonder if it’s also just a generational thing. I don’t know if you experience that in your classroom. So even the conversations we have around art and creativity … the students have their own language, the Gen Z their own language as to as to arts and creativity. So I do enjoy those moments in the classroom where cultural exchange, well give them a little tidbit about where I’m from, you know, let me know, you know, whatever it is they’re discussing culturally. I don’t hold it against them either. I’m used to it. I mean, also are you French? No ZImbabwe is in Southern Africa. French, I don’t know what that means. Yeah, we’re so used to that. But that’s so cute. Don’t judge me… Togo is like Central Africa. Tell me I’m right. Central frica?

CLAUDE

I always know now I always say Togo in West Africa just so they can know. And then when I want to be more precise to say Togo, next to Ghana in West Africa

NOVUYO

I feel bad because I did not know Togo was next to Ghana at all.

CLAUDE

I’m going to scrap this interview. I’m going to delete everything from this interview. This is really a great way for me to ask you about your current relationship to Zimbabwe. Do you go back? What is your you know, affinity at this moment?

NOVUYO

I went back last year in 2020. I mean, my relationship with Zimbabwe is complicated. And it’s probably going to get more complicated, on a political level. You know, it’s it’s always nice to be home. It’s very emotional, but it’s also frustrating.

We, you know, we have become the quintessential post colonial nation. You know, there’s this trope of a downward spiral, without a visible end. And that can be a bit depressing, but there’s also a sense of life going on. Zimabweans are… people living life, people enjoying life as best they can? So maybe those two dichotomies for me, which is the dream for Zimabwwe, what we’re capable of as a people what we’re losing, but also a sense of just… history. Right? People have dreams, people move and people enjoy their lives.

Because I’m, you know, I am I identify as queer. I went to Zimbabwe with my partner, who’s Jamaican, she’s a Jamaican American writer. My relationship in Zimbabwe has become a bit more complicated. I don’t know if I will go home again anytime soon,

CLAUDE

Because of the homophobia ?

NOVUYO

Becasue of the homophobia. But I will tell you interestingly, a lawyer friend pointed out you know, in Zimbabwe, there’s no actual legal law. Right? There is no legal law against LGBTQI people but there’s social persecution but even then, that she was saying Zimbabwe is so patriarchal that no one ever speaks about queer relationships between women. It’s always the law or the fascination is always around, sort of male to male relationships, which is for me very interesting about how the country conceives of women. Of course, one worries for one’s safety, and also just social stigma. Having lived in the USA for 10 years. I find myself quite intolerant of the social stigma against queerness. And so that’s not for me more than the legal it’s a societal shame that becomes difficult to navigate.

CLAUDE

And I’m wondering, given that you mentioned earlier again, Tsitsi Dangaremba, the acclaimed Zimbabwean novelist and playwright. Can you tell us perhaps about some other African perhaps women, African writers that you admire? That might have influenced you? Beautiful,

NOVUYO

Beautiful, you know, of course there’s NoViolet Bulawayo, brilliant writer, and just doing the work.

CLAUDE

Now, let’s go come out of Zimbabwe a little bit.

NOVUYO

Let’s find a way to you, you mean globally, in

CLAUDE

African globally or in the African diaspora, or, or even on the African continent? Outside of Zimbabwe?

NOVUYO

I guess Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

CLAUDE

How surprising

NOVUYO

I went to a workshop , you know, in 2009, I went to the Purple Hibiscus workshop in 2010. Run by Chimamanda that was my for me my first exposure, I think, to sort of inter inter intercultural exchange in art and that was transformative for me. So she she, you know, she’s really done a lot for for many of us young African writers in terms of those fundamentals. Alexia Arthurs, who’s a Jamaican writer

Audrey Lord who I’m currently actually reading for some nonfiction work Paul Marshall, Toni Morrison. Zukiswa Wanner who’s a South African writer, Pumla Dineo Ggolaa a South African writer. I’m going to go back to Zimbabwe again I mean, her name escapes me. Butterfly burning butterfly. So

CLAUDE

I didn’t read that. If it’s a novel as I said, I wouldn’t have read it.

NOVUYO

Yvonne Vera, one of the iconic writers she was writing in the 80s and 90s. In Zimbabwe, you have to read one, read Butterfly Burning. So it was just some of the women whose shoulders I stand on and continue to rise on.

CLAUDE

Beautiful, beautiful. Well I want to thank you Novuyo Rosa Tshuma for this fantastic interview. We had a lot of fun. I certainly had a lot of fun. I don’t know about you, but it was great to learn about you and your and your creative process and your migration and your dreams and aspirations. This is fantastic. So I look forward to staying in touch.

NOVUYO

It’s been a pleasure Claude. Thank you for having me.

CLAUDE

Thank you.

NOVUYO

Bye

CLAUDE

I hope you enjoyed this episode. It should give you some ideas on what to read next! Remember to leave a review if you are listening on Apple podcasts. If you are listening on Spotify, please subscribe. And if you are listening on any other platform, please share it with your friends.

Listen next

"It wasn't just an overnight thing. Seeds were planted."

With guests: Maya Horgan Famodu

LISTEN NOW 55 min

How did I make my first million?

With guests: Maya Horgan Famodu, Moulaye Taboure, Moutagna Keita

LISTEN NOW 15 min