February 1964. I’m seven years old when my mother wakes me at 2.00 am to watch a boxing match with her on TV. What? Why? Well, it’s taking place in America, in a place called Miami Beach, and one of the fighters is a cocky young kid, really annoying but very clever. Huh?

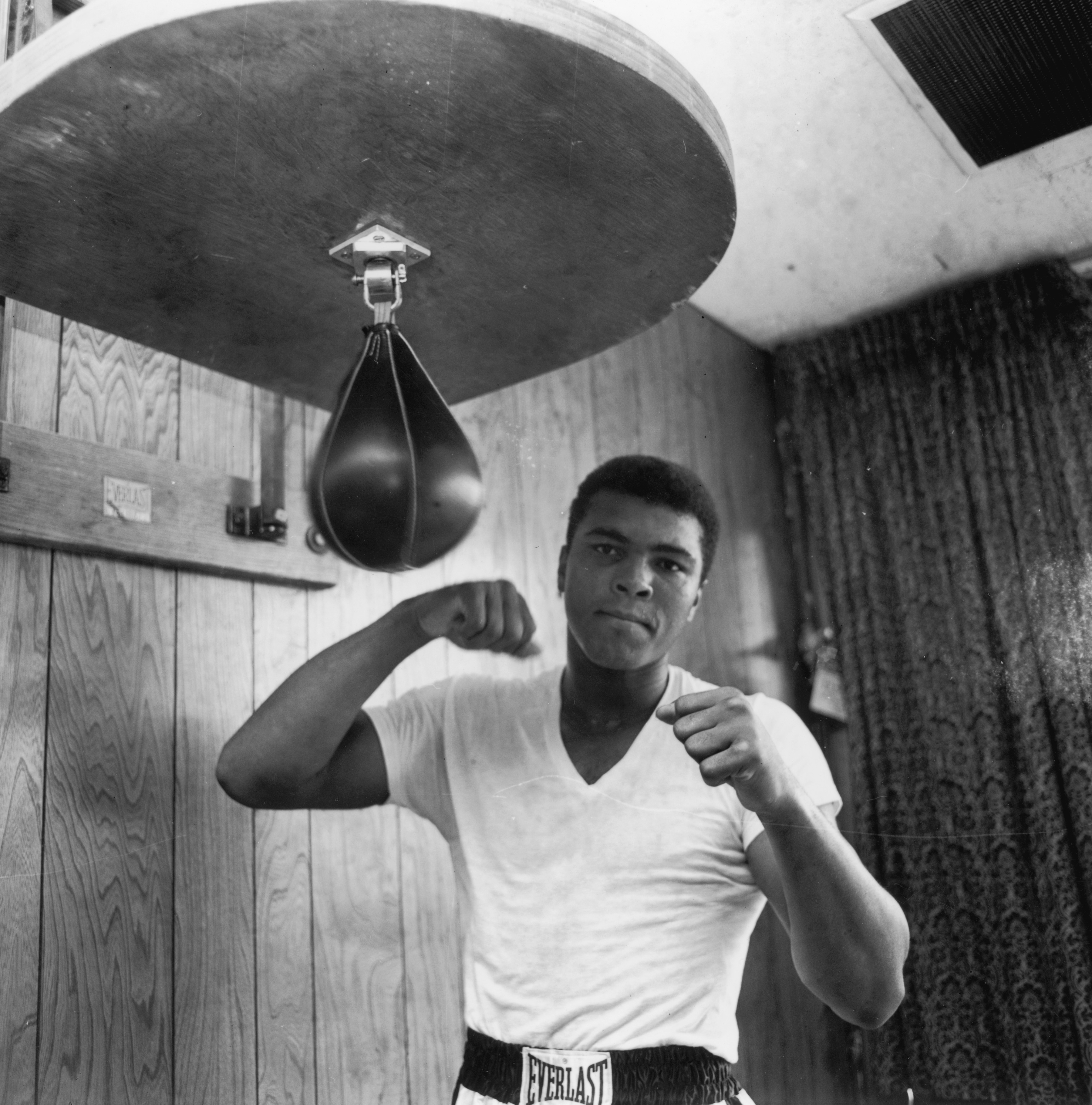

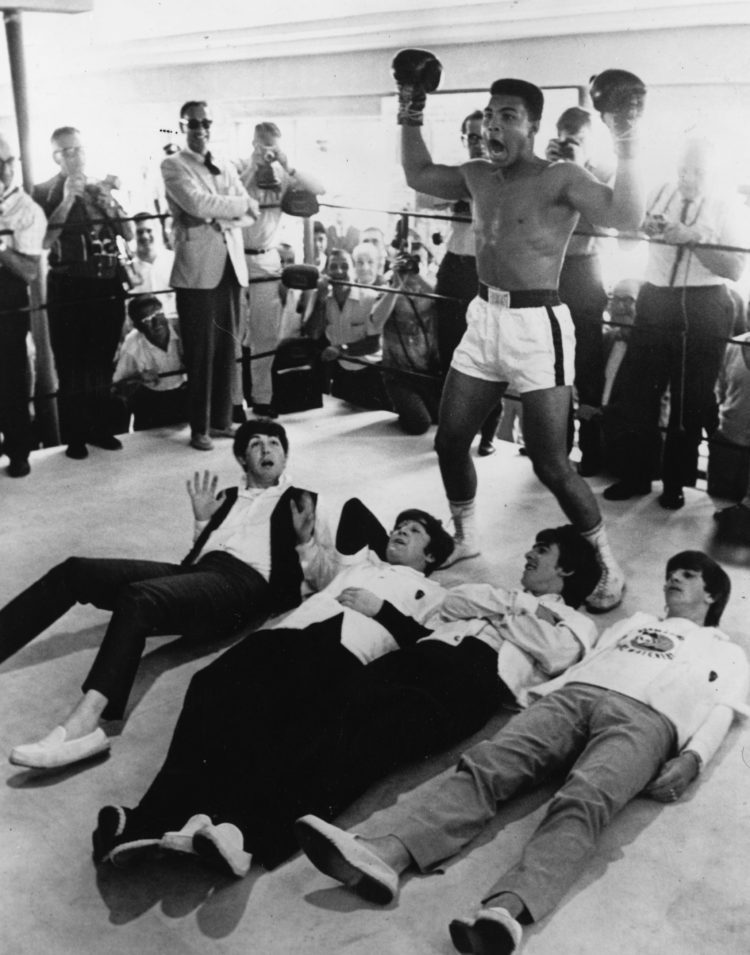

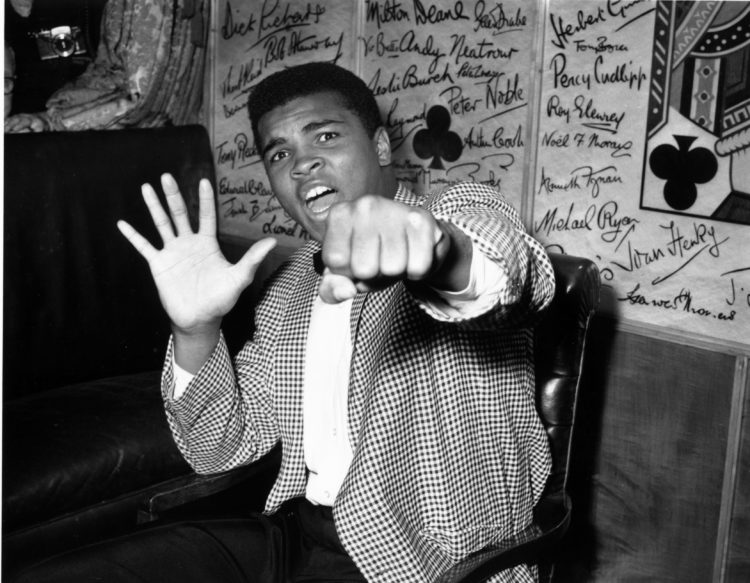

The grainy black and white pictures are miraculous to me: one of the earliest live transatlantic broadcasts. And when the underdog Cassius Clay emerges triumphant, the world suddenly seems smaller yet infinitely more complex. Here is a young black American who isn’t like those polite and deferential fellows on TV shows. Cassius Clay is a manic, wild-eyed, smart-mouthed and absolutely beautiful boxer who has just become heavyweight champion of the world at the age of 22.

He’s very good looking but he’s too cocky by far.

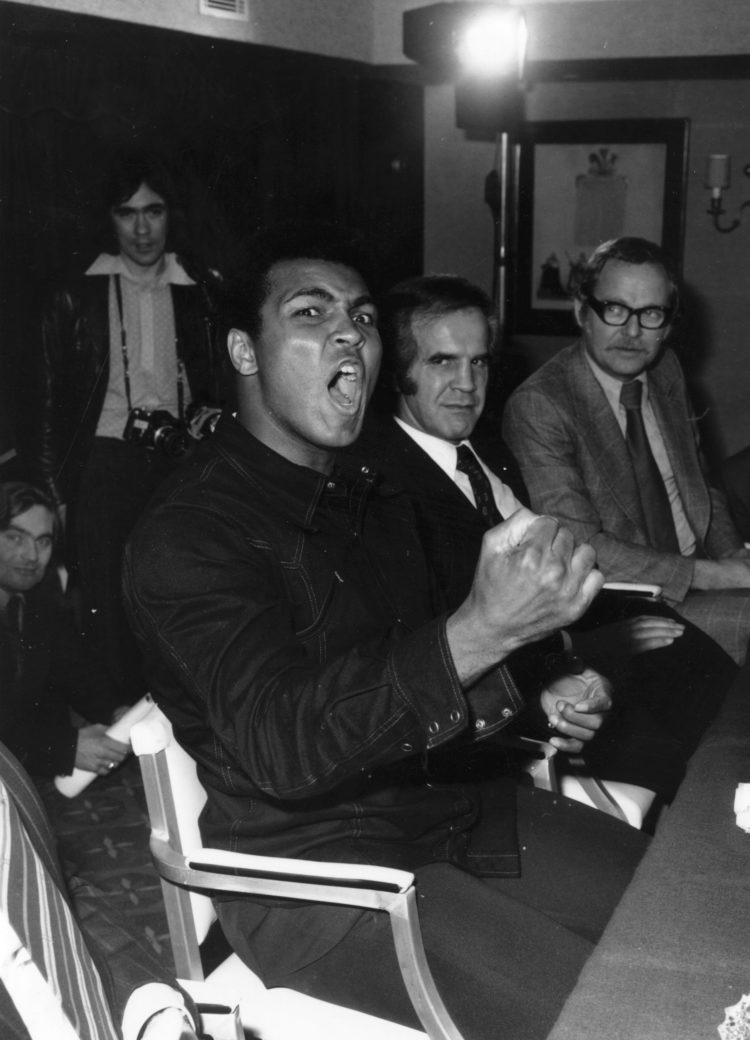

In mid-60s England, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones were already shaking the foundations of a sclerotic post-colonial society, but this is something even more vital and dangerous. ‘I am the greatest,’ Clay shouts directly at us as we sit together, open mouthed, on the sofa. ‘I’m the prettiest thing that ever lived.’ ‘He’s very good looking but he’s too cocky by far,’ says my mother. Even at seven, I can recognize her unspoken arousal. Turning back to the brash, unrepentant young man onscreen, I recognize something else: the knowing, playful glint in Clay’s eye. He’s mocking us! He’s just pretending to be crazy, just to make us laugh aloud, or spit with anger! And he doesn’t care which! I am electrified.

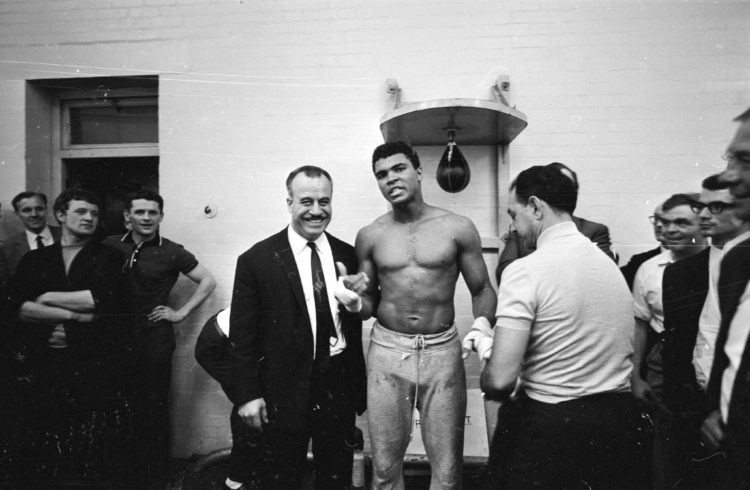

My little friends and I march around the playground chanting ‘Cassius Clay! I am the greatest!’ But we have barely grown tired of this game when Clay changes his name to Muhammad Ali. As I piece together why — with help from my mother, again — I am amazed to realize that such a thing is possible: you can change your name, and thereby change your identity. You can redefine yourself and throw off categorisation. This realization will change my life. Meanwhile, in the ring, Ali continues to beat all comers.

Literally, the world’s best fighter refusing to fight.

1967. At the height of the Vietnam war, Ali refuses to be drafted and fight. Literally, the world’s best fighter refusing to fight. Once again, my mother explains to her 10-year-old son how Ali could have taken the Elvis route, got an easy posting far from combat. Instead, he took a principled stand and was criminalised and stripped of his title. At this point, I start to mentally fold Ali’s name into my own, changing Alexander into Alix.

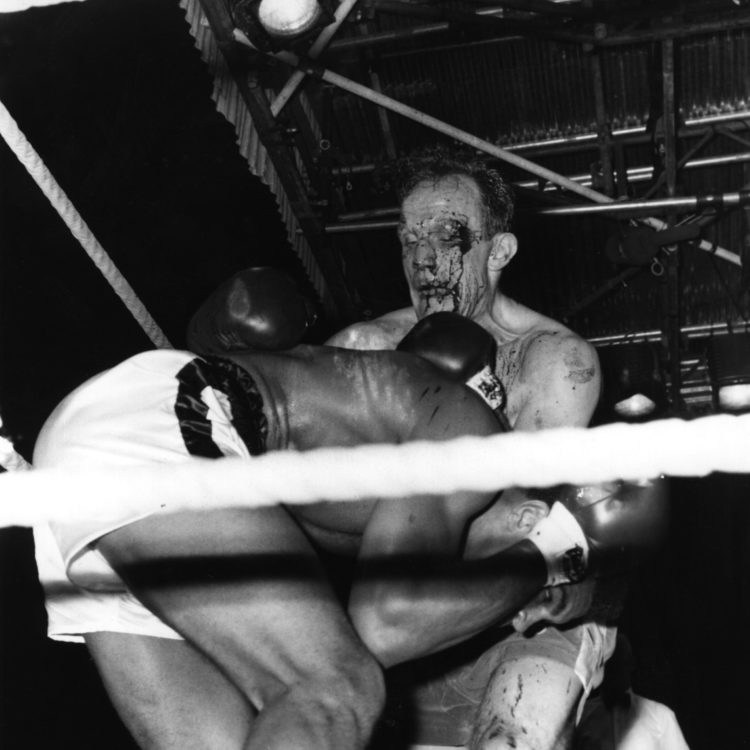

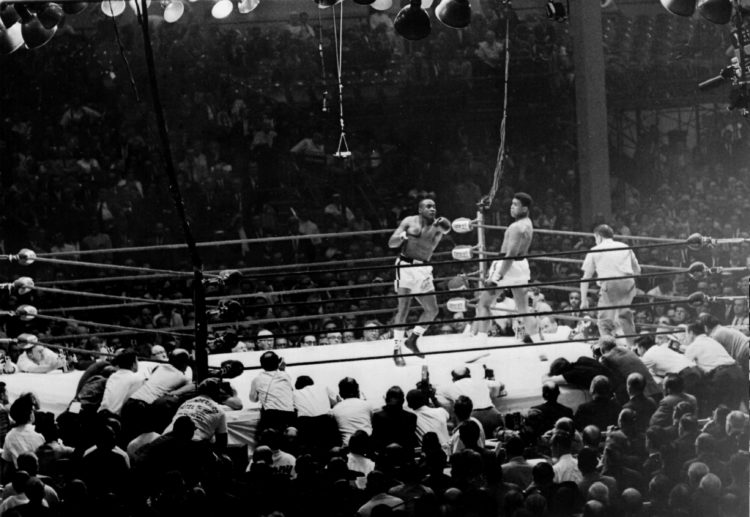

Skip to 1974, and having regained and re-lost his crown, Ali engages in the Rumble in the Jungle, versus George Foreman. Against all odds, Ali turns boxing science on its head with his rope-a-dope strategy, allowing the sport’s hardest puncher to exhaust himself with body blows before stepping into the ring and knocking out Foreman with a devastating combination. The strategy is typical Ali: reckless, fearless, and brilliant. Next year I buy a book entitled Muhammad Ali: The Holy Warrior, by Australian journalist Don Atyeo, who had been part of Ali’s camp, and ringside at the fight. I read and reread it, and then copy the best photographs to present the drawings as part of my art school application portfolio.

In 1977, I’m an art school punk sitting in a London cinema watching a live screening from Madison Square Garden, Ali versus the fearsome Ernie Shavers. Though Ali gets a unanimous decision, to me it looks like a draw at best. I no longer want to see him fight: the lightning speed is fading fast.

In 1980, I finally ‘meet’ Ali. British boxer John Conteh opens JC’s restaurant, where I work as a busboy. Opening night, Ali arrives and everyone swarms him, leaving Billy Idol to pout at empty space. Ali’s burger arrives and 60 people crowd around the table waiting for him to bite into it. He says, ‘Can I get some ketchup?’ There was none on the table! I fly into the kitchen and back, scrambling beneath legs so nobody can take the ketchup from me, surface beside him and hand the ketchup to my hero, who smiles and says, ‘Thank you.’ I’m confused: his hands are trembling and his speech is slightly slurred.

The punches keep getting stronger, but the heads aren’t getting any harder.

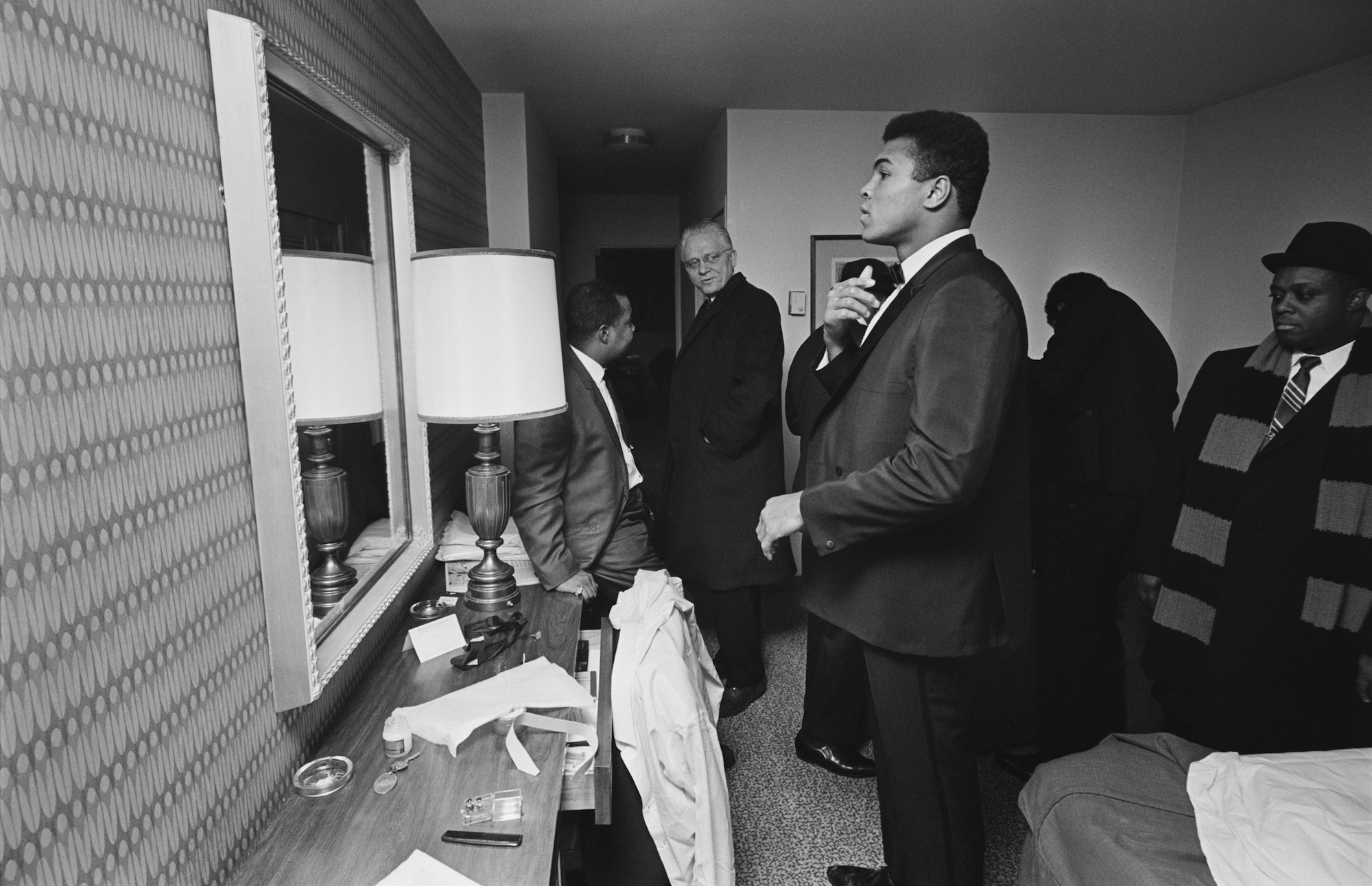

In 1984, I’m working for Time Out in London, under editor Don Atyeo. He tells me how he’d been with Ali in his Kinshasa hotel room following the Foreman fight. How he’d used the toilet after Ali, who was so exhausted he’d forgotten to flush. ‘The toilet bowl was full of blood. Foreman had hit him so hard to the body that his kidneys were still bleeding.’ Don also tells me he could never really enjoy heavyweight boxing after that: ‘The punches keep getting stronger, but the heads aren’t getting any harder.’ Around the same time, Ali retires. Shortly after he’s diagnosed with Parkinson’s, a degenerative brain disease linked to repeated head trauma.

2000: Now living in Paris, I interview William Klein, whose 1964 film Cassius, The Great is a scorching document of Ali’s early days. White southern tobacco barons discuss the young fighter like a piece of livestock, a thoroughbred animal. You can see Ali’s resentment simmering through his cold-eyed objectivity: he had knowingly submitted to this treatment in order to seize his chance.

In 2004, I move to Miami Beach and discover — to my astonishment — that I now live just a few blocks north of the old Fifth Street gym, where Ali had trained for all his early fights. And a few blocks north is the Miami Beach Convention Center, where he’d first won the heavyweight championship, 40 years earlier — while I’d watched alongside my mother, 3,500 miles across the Atlantic ocean. Some kind of circle is complete.

Now he’s gone — the last of my living heroes.

Ali has danced in and out of almost my entire life. And now he’s gone — the last of my living heroes. But as my daughter replied when I said as much: ‘At least you lived in an age of heroes, when people changed things rather than merely accumulating Instagram followers.’

There will be new heroes for future generations, and I’m pretty sure they’ll come from continents other than North America. But in my lifetime, there will never be a greater, more dazzling or noble hero than Muhammad Ali.

RIP.