I live in Jeppestown, a former industrial area on the eastern edge of Joburg’s CBD that is currently undergoing an ‘urban regeneration’ project aimed at ‘bringing people back to the city’.

The statement assumes that there weren’t people living there before. That the Zulu men, who still travel from their hustles in town, don’t exist and that the businesses which have been operating here before 2010 (when the Maboneng Precinct undertook its gentrification operation) weren’t around.

Part of the problem with gentrification – and there are many – is that it creates an imagined ‘new’ which isn’t rooted in acknowledging and including that which came before. It’s a big-ass erasure project where people are expected to believe that it’s all good, and new, in the hood. But enough of that.

Who's gentrification benefitting? | I took these images this morning in Jeppestown at an eviction pic.twitter.com/oJA1HEGc0h

— Kgomotso Tleane (@Kgomotso_Neto) November 17, 2015

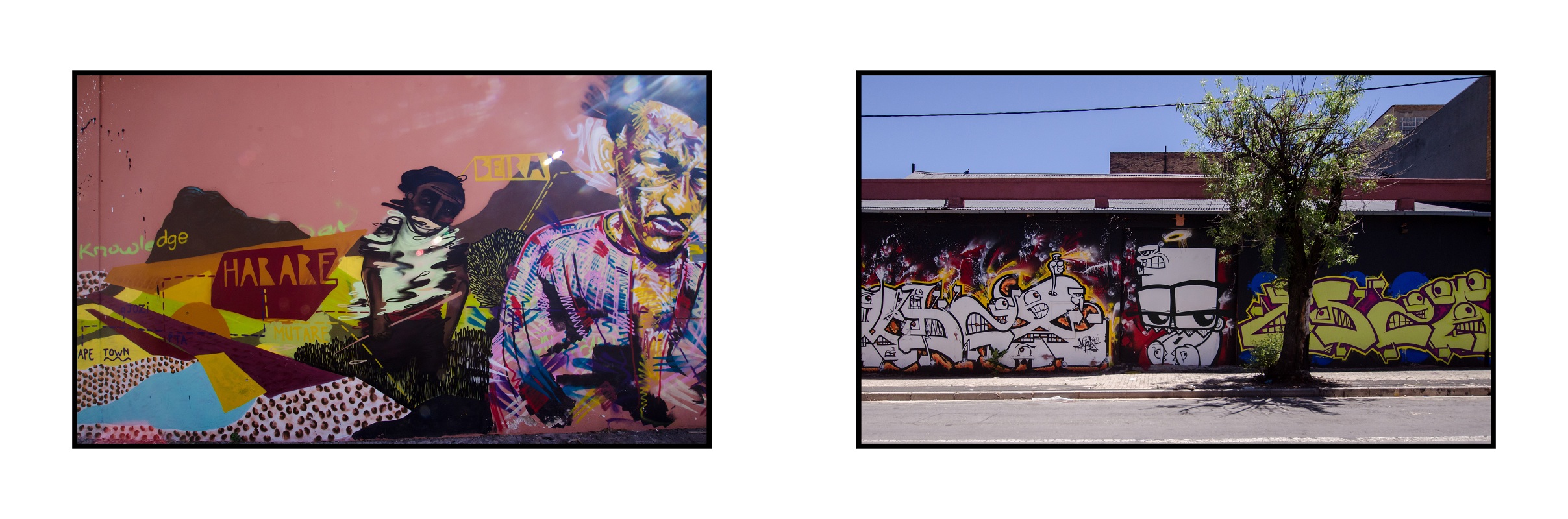

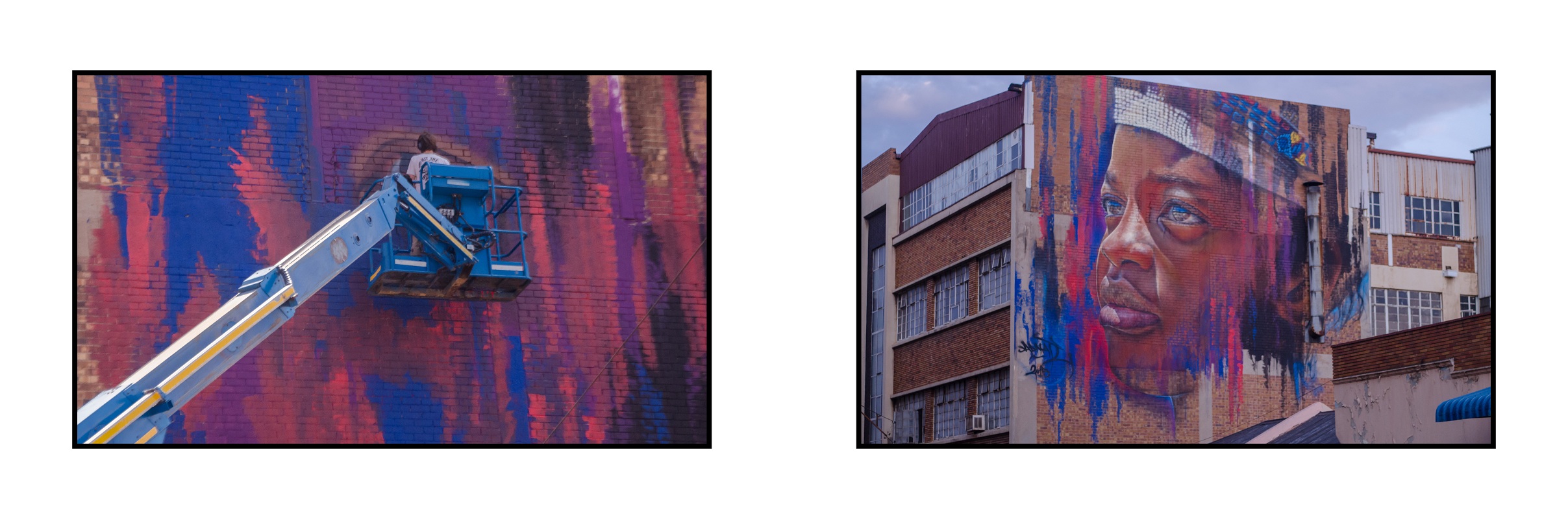

The street art tours undertaken as part of one company’s street walks have, as far as I’m aware, failed in exposing people to the walls beyond Maboneng’s confines. This part of town is generally run down; there are a number of abandoned buildings with great walls laying bare; artists, here and in Troyeville, either stay up by filling vast spots with their tags, or paint murals. The City of Gold festival, an urban street-art event which happens every year, has Jeppestown as one of the areas where artists, both SA-based and from elsewhere around the world, can come and paint their truths over a week-long period.

Today's activity INNERCITY TOUR #discoverjoburg pic.twitter.com/DbbhiSulf1

— Discovering South Africa (@mainstreetwalks) December 29, 2015

I realised that some monumental pieces will continue to come and go without being seen. Besides some old white folk who flock into the city on Saturday mornings with their cameras on ‘guided walks’ to perform their anthropological missions, there isn’t a lot I’m aware of being done to document the new works popping up on the regular. So I decided to do something about it by photographing not only the pieces, but noting the street corners on which they can be found and the names of the artists who put them up. Below is a selection of images, and text giving a bit of background to the scene.

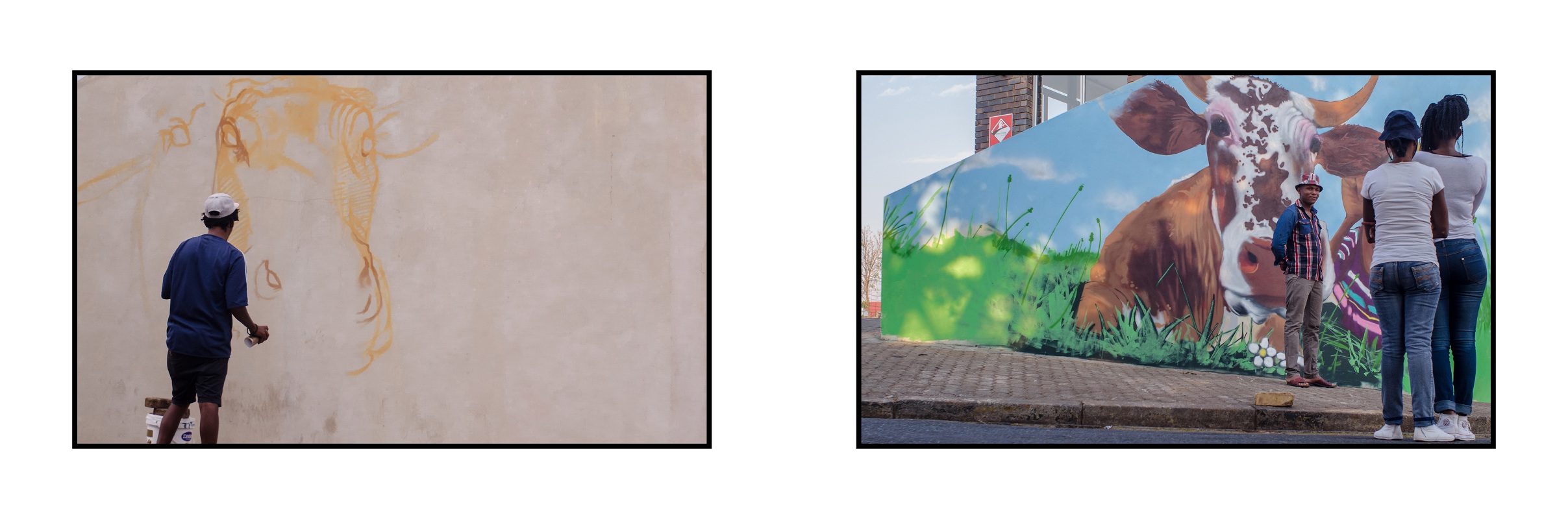

The fascinating part about having these works going up is seeing how people interact with them. While photographing Breeze’s piece, for instance, it was intriguing to witness the deep connection felt by the locals, most of whom are from the rural parts of the KwaZulu Natal province.

They’d take a moment from wherever it is they were going in order to admire it; some even posing for pictures using their mobile phones. As Breeze said while working on it: ‘I adapt my work to the environment that I’m working in.’ People’s reaction is evidence enough that he nailed it.