Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) affect over one and a half billion of the world’s poorest people, including more than 800 million children. Many of the more than 170,000 people who die each year from—or whose lives are affected by—NTDs live on the African continent. The good news is that NTDs are treatable and preventable, and the annual cost of treatment is very low. Since 2012, an organization called The END Fund had been raising private capital in order to launch or expand NTD programs all over Africa. Recently named one of TED’s Audacious Projects for 2019, The END Fund helped treat close of 100 million people in 2017 alone.

We interviewed END Fund CEO Ellen Agler just before she was named one of Fortune Magazine’s World’s 50 Greatest Leaders. The occasion was the publication of the book Under the Big Tree, which she penned with writer Mojie Crigler as a series of stories about those struggling with NTDs and the public health professionals who have devoted their lives to helping them.

How are you hoping the African stories told in Under the Big Tree will attract public attention in Western countries for NTDs?

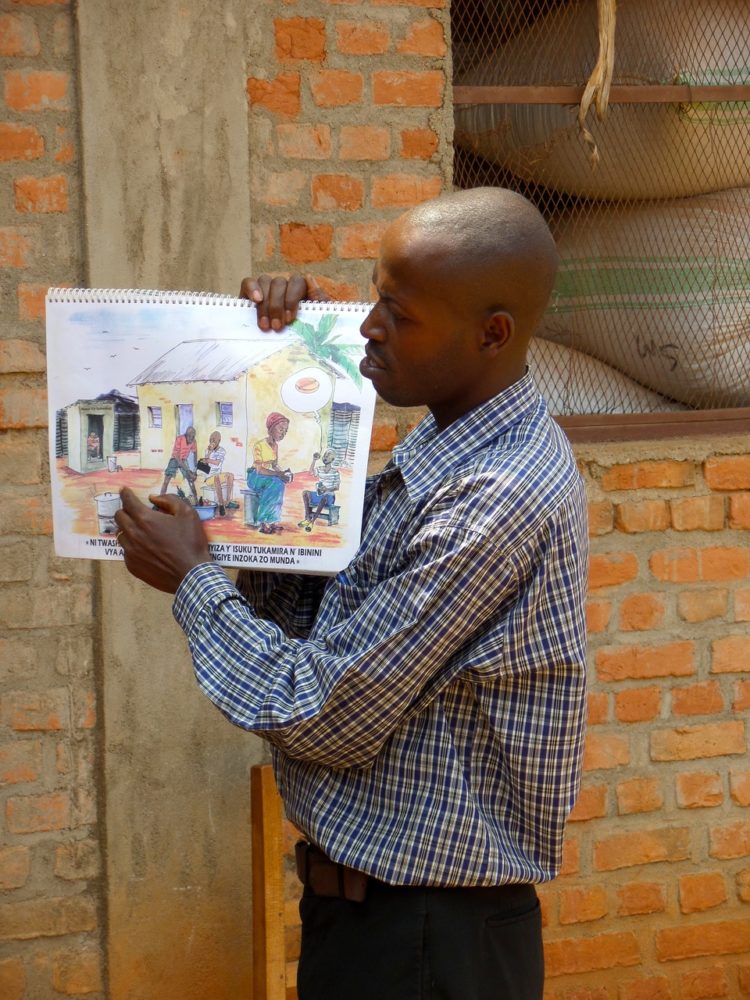

The stories explain NTDs—transmission, impact, and methods of treatment and prevention—but they are also about the amazing, inspiring men and women working to end these diseases. I’m hoping that through these stories, readers will see that lifting the burden of these diseases is not only possible but already starting to happen. And I hope that readers are inspired to get involved.

But these stories are not meant to only attract attention in Western countries, I hope they will inspire young Africans on the continent and those in the diaspora. These diseases are often unknown even within the countries where they are endemic because they often affect the most vulnerable or marginalized. I want these stories to both show Western audiences that they can play a role and show how this generation of Africans is even more crucial to tackling these diseases by engaging in everything from advocacy to programming to policy to end the suffering caused by NTDs.

In the book, you reveal interesting anecdotes around the ability of smartphones to help end NTDs. Please share your favorite smartphone story.

It’s hard to pick just one! There are many inventive ways that smartphones are being used to fight diseases. My current favorite smartphone story is the Global Trachoma Mapping Project (GTMP), which provided the first comprehensive worldwide map of trachoma. GTMP was completed in just over three years, a remarkable feat. The field teams included a grader (who looked at people’s eyes to determine if they had trachoma and, if so, how severe) and a recorder (who used a smartphone to record the location and the trachoma data). Once the smartphone was on a wireless or 3G network, the data went to a secure server and then to a data manager.

The data revealed that there were places previously unknown to be endemic for trachoma, and well as places that did not need treatment. This enabled programs to be streamlined, thus optimizing resources. It was a monumental effort. The teams visited twenty to thirty villages per district and sampled thirty or so households per village, so 2,000 to 4,000 people per district, for a total of 2.6 million people (or 5.2 million eyes!) globally. Without smartphones capturing and helping analyze data, it would have taken years to analyze this data and make it useful to design programs for people who, without treatment, we’re at risk of going blind. It’s phenomenal—this modern device being used against this ancient disease.

The 2012 story around the bedrock of Mali’s success in treating specific diseases was inspiring. What can we learn from the Malians and that particular experience?

Prior to 2012, Mali’s NTD program was one of the first to integrate treatment for several NTDs (intestinal worms, lymphatic filariasis, river blindness, schistosomiasis, and trachoma). This approach had proven very successful: higher coverage, lower costs, lower disease prevalence. So, the first lesson we can learn from the Malians is their willingness to try something new.

The second lesson we learn is from Dr. Massitan Dembélé, who spoke up at the 2012 conference of African NTD program managers. The coup in Mali, which had occurred a few months before the conference, meant that foreign aid, e.g., from the United States, was put in hold. Because Dr. Dembélé alerted the rest of us in the room that Mali’s NTD program was in jeopardy, the global community was able to rally, find funding, and ensure that the program continued, uninterrupted. So that second lesson is to use your voice and be open to totally new and unexpected partners to solve a problem.

Why was the famous Guinea worm program successful in Ghana?

Since the END Fund doesn’t work on Guinea worm, we aren’t best placed to speak to this. However, that story highlights a commonality in other NTDs – through a strong training system and a network of community volunteers, NTDs can be tackled from within the community. The Guinea worm program used a strong network of village volunteers, which the trachoma program was able to leverage. Ophthalmic doctors and nurses were able to train these volunteers to find and treat trachoma cases and have this rollout nationally.

A successful NTD program is owned from within and can lay the groundwork for a better health system for responses to other public health issues as in this example with the Guinea worm program. Also, the massive progressive toward eradication—literally from a time when millions of people per year had this painful, debilitating disease just a few decades ago, to now a few dozen—shows that progress to get to the end is possible, with collaboration, clear goals, persistence, and a willingness to tackle unexpected challenges during the final mile “end game.”