Art museums can be some of the most conservative institutions on earth. Many people find them boring, because they tend to focus on the past, on histories that mean little to young people. In today’s digital age where many of the rules of artistic creation are being rewritten at an accelerated pace, who needs another museum focused on heritage when we should be looking at the future?

These are legitimate questions if you live in big cities in the Western world, where museums can be found in seemingly every neighborhood, but in an African capital like Lomé, the opening of a national art museum is a big deal. The (overused) term “Bilbao effect” feels appropriate because, as with the opening of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in 1997, it points to the cause and effect relationship that can be traced to a single world class project that leads to the revival of a previously underserved metropolitan area.

The hope for many residents of Lomé (which happens to be the city where I was born) is that the state-funded art museum in question, the Palais de Lomé, will help transform their city into a destination for art lovers, and that this should happen through the fostering of a thriving cultural sector. Drawing a parallel with Bilbao might sound contrived to some critics and commentators who look for starchitects and hypermodern display spaces, but this particular architectural iteration—a renovation of a historic building—helps in spotting faulty comparisons.

Togo has a complicated political history, which includes 38 years of military dictatorship, and many of Togo’s more prominent cultural figures were forced into exile in the early 1990s. Some dissidents (or some of their children) became successful in Europe and America, but few returned to live or work in their native country when the country began its march toward democracy.

After a series of political, economic and social crises in the 1990s and 2000s, Togo was shunned and portrayed as a wasteland by Togolese artists and writers who rarely spoke about the possibility of future artistic regeneration in a land they were now at odds with. In that sense, the Palais de Lomé can be seen as a gesture of goodwill offered by the President, Faure Gnassingbé, to those who turned their backs on Togo.

I happen to be one of those diaspora Togolese who have always believed in Togo. In the week before the public opening of the Palais de Lomé on November 26th, 2019, I started hearing from quite a few art world friends who live in various cities around the world. They wanted to tell me that they had already booked their plane tickets, that they had secured hotel reservations, and that they would soon be visiting my hometown. Some would be coming for the very first time.

Alana Hairston, the New York-based director of programming at The Africa Center was curious about the Palais, and she also wanted to know if there were any Togolese people and initiatives that The Africa Center should connect with. Meryanne Loum-Martin, the founder of both AFreeCulture diaspora events and an owner of Jnane Tamsna boutique hotel in Marrakech with her ethnobotanist husband Gary Martin, told me that they were on their way. Adora Mba, the London and Accra-based founder of The Afropolitan Collector once worked with me at TRUE Africa; she informed me that she too was Lomé-bound, and that she would be showing up with her crew.

On my Paris-Lomé Air France flight, I ran into Rodolphe Blavy, a Paris-based IMF economist and author who collects African art in his spare time, and Ijeoma Ndukwe, a London-based journalist who writes for the BBC (and once worked with me at TRACE Magazine in New York City), and also André Magnin, a Paris-based gallerist who is known for having curated most of CAAC, otherwise known as Jean Pigozzi’s Contemporary African Art Collection. And then the Lomé-born, Abuja-based, multimedia artist Modupeola Fadugba wrote to me, apologizing that she was unable to make it to the opening, while mentioning that she was sending her Godmother to go in her stead.

All of those artsy friends wanted a primer on the building itself, but mostly there was some excitement around the fact that a new seafront museum in Lomé was attempting to put Togo on the international art map. As a native son, I’ve spent my life pointing to my birthplace on all kinds of maps of West Africa. Sometimes, I would describe Togo to Americans as that small, Francophone country roughly the size of West Virginia that happened to be stuck between Ghana and Benin. I would always say that Togo is not too far from Nigeria in West Africa, which is not a country.

The Palais de Lomé is a converted palace, which used to house German and then French Governors of Togo. A symbol of colonial rule, which in Togo lasted from 1884 to 1960, when the Togolese Republic was proclaimed, the building, which was initially completed in 1905, is a stark reminder of the times when foreign rulers controlled the destiny of this tiny nation. Eight years ago, Gnassingbé decided to allocate public funds to an ambitious renovation project that would be centered around his vision of turning that dilapidated former colonial building into a venue for Africa’s creative expression.

Sonia Lawson, a Togolese former luxury goods executive who previously worked for large French companies including LVMH and L’Oréal, spearheaded the entire project around an idea that the Palais de Lomé should become a major destination for people who care about art, culture and biodiversity from a broader African perspective. With the help of a trio of architecture firms, Segond-Guyon, Archipat, and Sara Consult, and the landscape designer Frédéric Reynaud, she relied mostly on Togolese companies, engineers, artists and craftsmen in her attempt to “reinvent natural and historical heritage to foster creative talents in Africa.”

With a population of roughly 7.9 million, Togo is a country that was formed over time through waves of migration, with various tribes settling in the land between the 11th and 16th century, before that coastal part of West Africa (the part along the Bight of Benin between the Volta River and the Lagos Lagoon) became known as “The Slave Coast.” “We have drawn from this transcultural past,” Lawson wrote, “to make the Palais de Lomé a place where African cultures are valued in the eyes of the world, as well as a center for African talents. We hope to contribute to Togo’s influence across the globe, while striving for excellence.”

In a fast-growing capital city with few public gardens, the 29-acre botanical park around the Palais is a wonderful achievement of respectful, eco-friendly landscaping in the way it manages to preserve centuries-old tropical trees while allowing medicinal plants to grow in the green spaces as the 40 odd species of birds circle their way around the park. In that spirit of environmental friendliness, the Palais has been protecting its beehive for pedagogical purposes, and visitors will be able to buy honey from the Palais boutique.

After a walk around the baobabs, palm trees, and the green foliage of the fern, the visitor gets to wander in the Sculpture Park, which showcases the work of artists including Amouzou Amouzou-Glikpa, who created a set of monumental bronze figures called Les Togolais (The Togolese) by the seafront entrance, and rising star Sadikou Oukpedjo, who utilized Togolese marble to carve out a series of African faces called Le Conseil des Sages (The Council of Elders).

I had met the 44 year-old, Abidjan-based, Togolese artist Oukpedjo at the Also Known As Africa (AKAA) Art Fair in Paris in November 2018, when Sonia Lawson introduced me to him. I’d been a fan of his work for a few years, having first seen it at the Cécile Fakhoury Gallery in Côte d’Ivoire. When we met again in Lomé at the opening of the Palais, it all started making sense when Oukpedjo told me that he had studied under Paul Ahyi, one of Togo’s best known artists. Ahyi, who designed the Togolese flag and created much of the public art in Togo, died in 2010, but his spirit lives on, and his influence on the new generation of Togolese artists is real.

“At this point of my life, I’m not looking for more galleries,” Oukpedjo told me. “I am already represented by two galleries, which bring me enough money so that I can support myself. What I really need now is for my work to be seen by more people, and by more Togolese people, by more people from my country. Togo is a very small country, that has a lot of energy, and I think people need to see that energy, to be reminded of that energy.” Oukpedjo, who was preparing for a big show in Berlin, seemed really proud to be involved so directly with the Palais. Other Togolese artists I spoke with at the opening were less patriotic, and perhaps more critical of the state intervention, but the pride was undeniable.

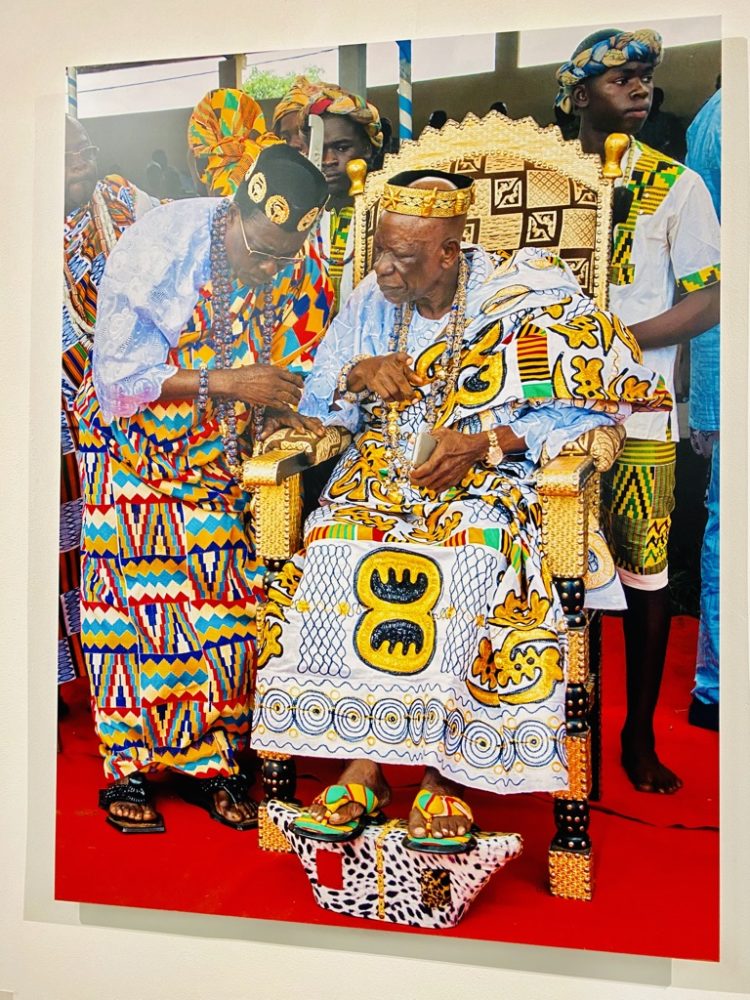

As I walked up the beautifully restored staircase above the entrance of the museum, I ran into the figurative painter Kehinde Wiley, an old friend from New York. Wiley, whom I’d collaborated with on two commercial projects in the past, was wearing a flashy blazer that was cut from the cloth of our traditional African wax print. A flamboyant Nigerian American who is perhaps best known for his portrait of Barack Obama, he told me that he’d arrived in Lomé right that morning, just in time for the opening. (I was told he’d missed his flight the day before.) “I really love it here,” Wiley said. “This is a beautiful country. I had to be here for this.”

The whole scene at the opening became quite social, but in an improvised procession, my Togolese and foreign art world friends and I slowly walked in and out of the galleries in what would be our first visit to the Palais de Lomé. As we admired the grandeur in the undertaking, while paying attention to the details in the fabrication techniques, we witnessed a new sort of programmatic audacity. The heritage behind that curatorial elegance felt very Togolese, very African and also very worldly. The Palais de Lomé is not a perfect museum, but it’s just the kind of museum a city like Lomé needs right now.

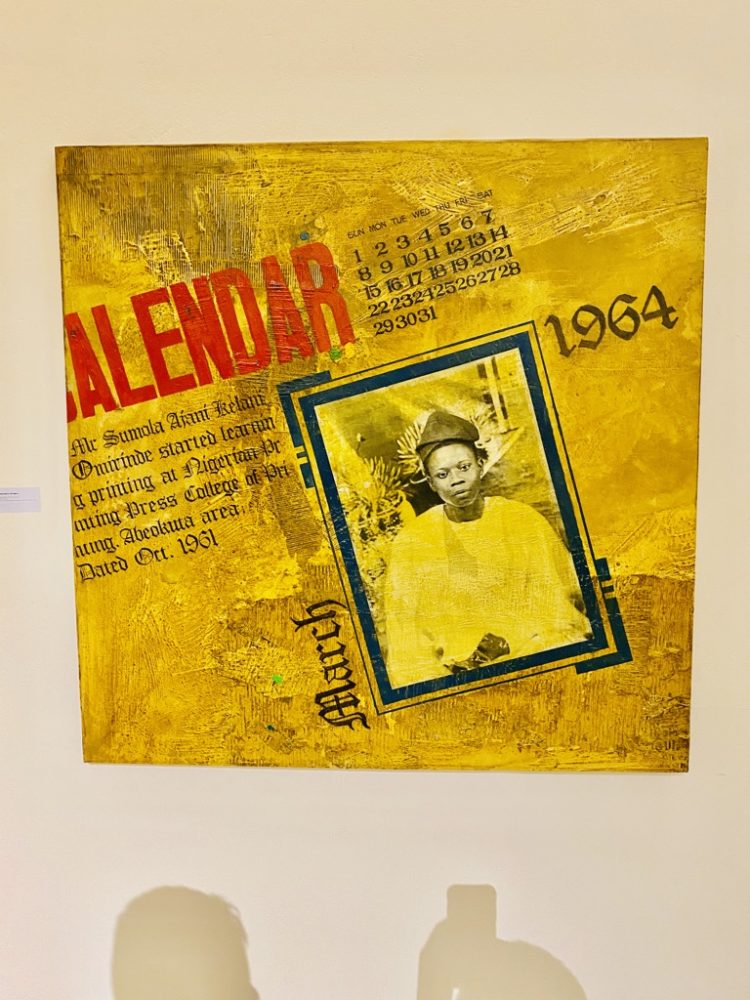

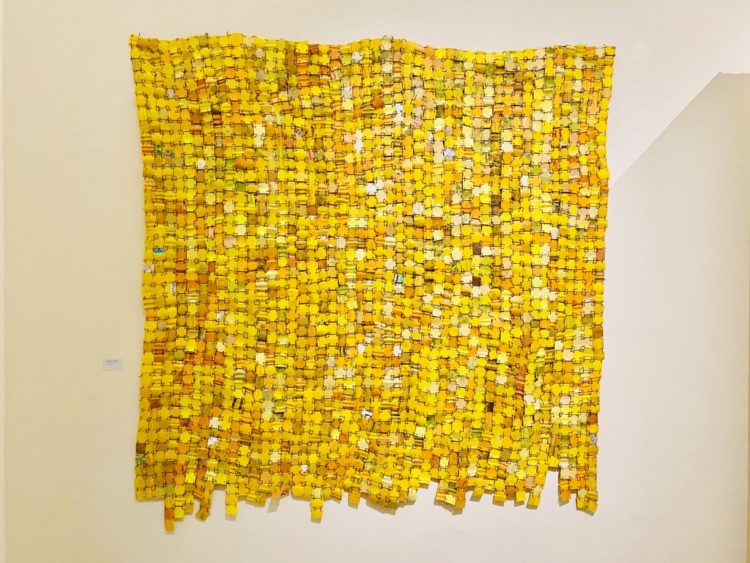

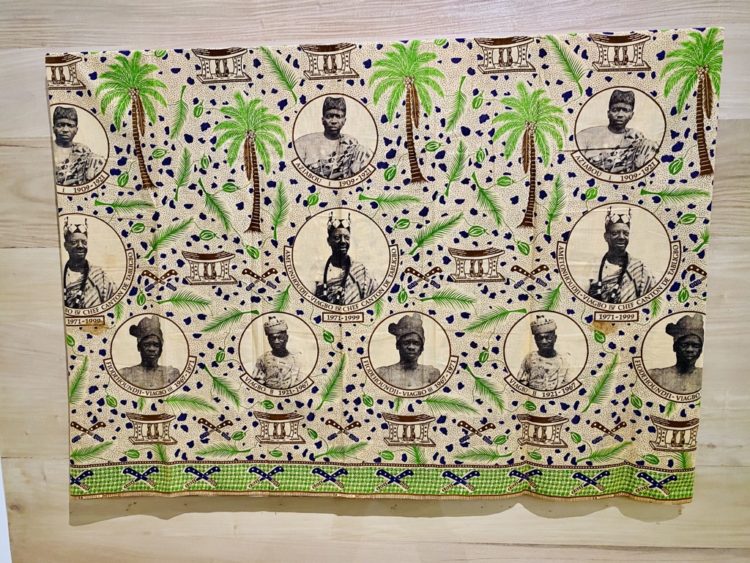

Below, are a few images from the inaugural exhibitions, which are meant to educate several generations of visitors, including the youth audiences Sonia Lawson and her team are targeting through a school visits program. Most notable are Togo of the Kings, which was curated by Kangni Alem; Infinity: Kossi Aguessy (1977-2017), which was curated by Sandra Agbessi and is dedicated to the late Togolese designer; and Lomé +, a Sename Koffi Agbodjinou curated exploration of the Togolese capital as seen through the lens of what a smart city should be; and Three Borders, an Aminat Agoro curated group show around the idea of a borderless Africa.