We are supporting Nigerian-American filmmaker Iquo B. Essien’s campaign to raise $30,000 to convert her family’s historical land in Calabar, Nigeria into a memoir gallery and space for Nigerian cultural preservation—along with a virtual gallery, accessible online, and a residency for African womxn artists.

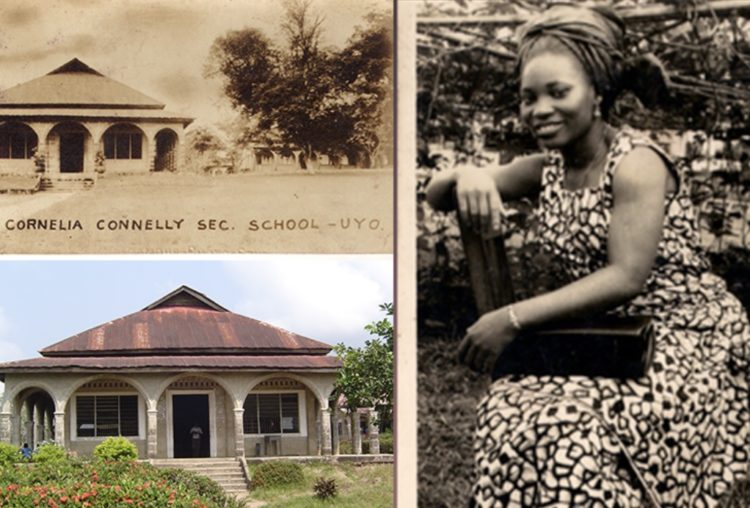

Essien recently learned that the land, purchased by her late grandfather, Chief Paul Bassey Okon, has been put on the market for immediate sale. The goal of the fundraiser is to secure the land and transform the home that stands upon it into the Elizabeth’s Daughter Memoir Gallery and Artist Residency. Prior to its construction, the land will also be the site of Iquo’s debut feature film inspired by her relationship with her grandmother.

We interviewed Iquo about this campaign, which is rooted in a research project she conducted for a memoir of her late mother, Elizabeth Essien, who had died of cancer. Elizabeth had always wanted to write her story, but she’d never gotten the chance—so Iquo took it up for her.

Where did the idea for Elizabeth’s Daughter come from?

I don’t entirely understand the question, but I will attempt to answer! In 2010, I found myself on leave from film school and recently unemployed, when I was invited to participate in the Future Leaders Seminar hosted by the Nigeria Leadership Initiative. It was a three-day summit designed to promote a cadre of leaders to move Nigeria forward through values-based leadership.

I had extended my ticket after the three-day program for several months. After greeting all my family, I needed something to do with my time. So I dusted off an old application I’d made for a travel grant (that I didn’t win) to write a memoir of my mother. I had a list of names of people to interview, sites to visit.

At a time in my life when I felt fairly lost, I found that the research project gave me a new sense of direction. It grew into a memoirette, Elizabeth’s Daughter in Words and Pictures, a series of linked essays and photographs that I self-published in 2013. The book examines my mother’s departure from Nigeria, her life and death, and my eventual return to remember and write about her, exploring issues of religion, politics, language, and identity. It is a story about a grief-stricken daughter turned bona fide writer—chronicling my journey as I uncover my mother’s life as a would-be nun turned wife, while coming-of-age as an artist and young woman.

I’d assumed that if I ever finished a book, there would be so much demand, but that wasn’t the case. Only eight of my closest friends and family bought it, lol! So I had always planned to rewrite the book, take it to a traditional publisher and gain a wider platform. But as the years went on, and I continued working on it, I gradually amassed a content archive of audio recordings, photos, video, archival documents, journals, and writing.

It became increasingly clear that the project was so much more than a book. I knew that my family’s story offered unique insights on the past 100 years of history of Nigerians at home and abroad. And the project made me a keeper of potentially lost history. I felt called to “liberate” the project from book form and bring it to a wider audience, while promoting other artists who do similar work.

That is the genesis of the Elizabeth’s Daughter project in its current form. But if you ask where the idea came from, I would say I felt called to do it. My mother had always wanted to write her memoir before she died, but she didn’t get a chance. So I felt compelled to take it up for her.

How do you think Elizabeth’s Daughter will help to preserve African traditions while looking to the future?

Cultural preservation for its own sake is not a common practice among Nigerians or the Ibibio; our cultural practices are a way of life, not something to be observed and studied. One might even interrogate the Western origins of archiving, exhibition, and preservation. Family picture albums, songs, dances, oral history, home burial sites, documents, and personal artifacts are some of the things that comprise our historical record.

But I have seen firsthand how poorly these elements are generally kept, shared, preserved and documented. And I’ve continued to wonder what becomes of us when our history, stories, traditions, and customs—already reconfigured by slavery, colonization, independence, war, and globalization—are perpetually lost to time.

I believe that preservation work should be prioritized in the Covid era. I’ve been in a race against time to interview elders before they’re gone, to document their stories, photos, video, and traditions, more urgently than ever before. While the live and virtual gallery exhibit aids in preserving my family’s story, offering a unique lens on the broader 100-year history of Nigeria from the early 1900s to the 2000s, the space will foster other artists engaged in similar cultural preservation work.

The explicit purpose of the endeavor is to preserve what we have now, so it can be passed down to future generations through in-person and virtual exhibitions. We need a global movement to promote storytelling, documentation, and cultural preservation. Without it, we’re in danger of losing our languages, cultures, and customs forever. This is the primary concern I think about every day, while wondering if I’ll have enough time to realize this dream.

How American do you feel when you are in Nigeria?

This is an interesting question. In America, I often feel very un-American; and in Nigeria, as my cousin says, I “blend in,” though at times I definitely don’t feel Nigerian enough. That my mother was in danger of being deported while I was in her belly, and my parents raised us steeped in our culture, explains the tenuous relationship I’ve always had with Americanity.

There are many things I never understood growing up because they weren’t in our culture, and even aspects of Black American culture that I had to learn. And though I appreciate the access it affords me, the privilege of two passports, and the marketplace of ideas that informs how I see the world, America can be full of inequity, injustice, and second-class citizenship.

So I don’t generally feel that American anywhere; I exist in two cultures—maybe more, if you count Black American culture—and am always negotiating space and dissembling depending on who I am around. For the sake of categorization, I hyphenate my identity: Nigerian-American. It reflects the reality of my heritage and dual nationality.

For my family, and Nigerians as a whole, the fate of people back home is bound up with that of those who left or were raised abroad. But I don’t see the two as 50-50, it leans more toward the Nigerian side. I am most at home around artists and creatives in Nigeria, existing in another dimension of our own creation, often going against the grain of tradition or society.

To learn more, visit this page. This campaign ends on April 25th, 2021.