When Jenny Cathcart travelled to Senegal in 1984 as a member of the BBC TV film crew that produced The Africans, she met with the rising star Youssou N’Dour. It was a fateful meeting which led to her abiding interest in African music and culture. When the term ‘world music’ was coined in London, Jenny was a producer on the pioneering TV series Rhythms of the World.

In 1995, she proposed an African summer season on BBC Two and produced two of the programs: the first ever African Prom and the documentary Africa’s Rock ’n’ Roll Years, a social and musical history of post-independence Africa. Ten years later, in 2005, she was series producer and director of BBC Four’s six-part TV series, The African Rock ’n’ Roll Years. While working at Youssou N’Dour’s head office in Dakar, she managed the artists Cheikh Lô, Orchestra Baobab, and Pape and Cheikh.

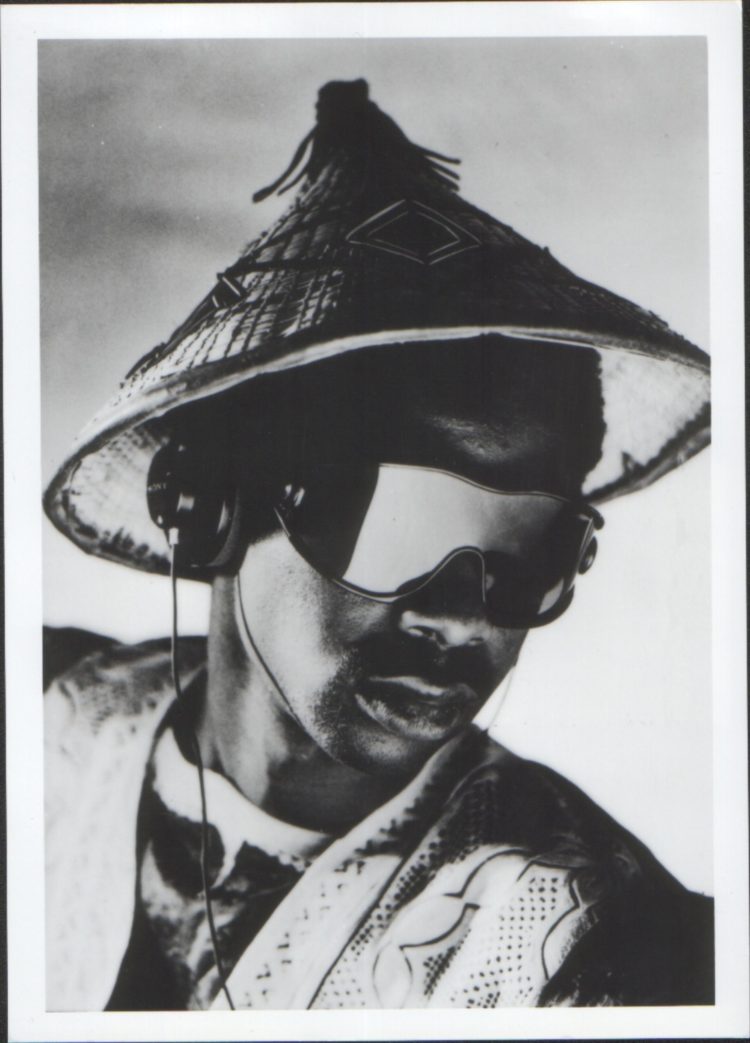

Yesterday, we published an excerpt from her book Notes From Africa: A Musical Journey With Youssou N’Dour. Today, we ask Jenny Cathcart about Youssou, the person who introduced her to African music just as a new musical phenomenon, termed world music, was beginning to emerge. Beyond Youssou, we also wanted to know about a few of those African musicians who embarked on a musical journey that eventually led to world fame.

Can you tell us more about the griot (storyteller) lineage that gave birth to Youssou N’Dour and allowed him to start performing at age 13?

Youssou describes himself as a modern griot acknowledging the natural gifts for singing composition and improvisation that he received from his mother Ndeye Sokhna Mboup and his grandmother Marie Sene. They are the most recent in a long line of hereditary musicians who served as praise singers, entertainers, advisers and keepers of history as far back as the great courts of West Africa and beginning with the Mali Empire founded in the 13th century by Sundiata Keita.

The Senegalese architect Nicholas Cissé defined Youssou’s place in the firmament of griots thus: “Each generation sang and spoke and the words accumulated until the day when a plethora of words fell on one griot who received the ultimate gift and became a megastar called Youssou N’Dour.”

Many people consider Youssou’s 1994 album The Guide to be his masterpiece. Why do you think that album, and the song ‘Seven Seconds’, which he recorded with Neneh Cherry, found an international audience?

One of Youssou’s first supporters in Senegal was the artist Issa Samb who told me, “Youssou is an innovator who has always surprised us. He is capable of working with any musician on the planet.” For Youssou The Guide in question is Cheikh Amadou Bamba, founder of Senegal’s Mouride muslim brotherhood. Dubbed the Ghandi of Senegal, Bamba set an example of peaceful enlightenment.

The international release of the album by Sony Columbia bore out Issa Samb’s observation. It includes ‘Seven Seconds’, Youssou’s duet with Neneh Cherry, a guest appearance by Branford Marsalis on ‘Without a Smile’ and an English/Wolof version of Bob Dylan’s ‘Chimes of Freedom’. London’s Guardian newspaper defined the album as “the finest example yet of the meeting of African and Western music: wholesome, urgent and thoughtful.”

‘Seven Seconds’ was recorded in New York and London and produced by Cameron McVey. It was he who provided the descending opening chords that open out on a beautiful melody. Released as a single ‘Seven Seconds’ topped the charts in several European countries. It notched up more than 2 million sales worldwide, gained seven gold discs and was named European Song of the Year at the 1995 World Music Awards in Monaco. Suddenly the voice of Youssou N’Dour singing in Wolof was heard on radio stations around the world and it raised his international career to a whole new level.

Do you feel that Youssou’s mouvement citoyen, called Fekke Maci Bolle (Since I Am Here I Am Implicated), altered the course of democracy in Senegal?

Since its independence from France in 1960 Senegal has been a fairly open, progressive and peaceful country. Its first President Leopold Sedar Senghor was a poet, a Christian in charge of a largely Muslim country. When Senghor’s successor Abdou Diouf was defeated at the polls by Abdoulaye Wade he retired quietly in France. Wade’s economic policies led to increasing inequality between Senegal’s rich and poor.

A political crisis developed in the run up to the Presidental elections in 2012. The 85-year-old president seemed determined to remain in power for a third term even if it meant changing the constitution. It was then that Youssou formed his political movement in support of democratic elections. When on January 2nd, 2012 Youssou announced his own candidacy for President he said it was his patriotic duty because dictatorships and corrupt leaders bring shame on the image of Africa.

He also believes that no African president should serve more than two terms. In the event his candidature was refused by the Constitutional Council but Youssou continued to support Macky Sall, another candidate who eventually became president and is currently serving a second term.

In early March this year when the PASTEF party leader Ousmane Sonko was arrested it appeared as though Macky Sall’s aim was to eliminate a potentially strong opponent at the 2024 presidential elections. This also implied that he Macky Sall would seek a third term as president. Protestors took to the streets and ten young men were killed. Calm was restored when Sonko was released and the President promised more support for the young and unemployed. The battle for a fair and free society continues in Senegal as elsewhere.

In the book, you describe the musical contributions of Salif Keita, Ali Farka Touré and the late Miriam Makeba. How did those three musicians become so influential (and popular) outside Africa?

Miriam Makeba (1932-2008) became South Africa’s most celebrated female singer following her appearance in the jazz opera ‘King Kong’. In 1959 in London she met Harry Belafonte who became her mentor, collaborator and ‘big brother’ when she moved to the USA. Makeba quickly found herself in exile (an exile which lasted 30 years) for when she tried to return home for her mother’s funeral the South African government annulled her passport.

In 1962 Belafonte and Makeba performed together at President John F Kennedy’s birthday celebration at Madison Square Garden, the same night Marilyn Monroe sang her famous birthday salute to the president. Their anti-apartheid album An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba was released in 1965 and won a Grammy award. In the US Makeba first married fellow South African musician Hugh Masekela and then the activist Stokely Carmichael.

Facing prejudice in her adopted country (her shows were cancelled and record companies reneged on contracts because of her relationship with Carmichael) the couple moved to Conakry in Guinea where President Sekou Touré asked her to represent Guinea at the UN; continuing to oppose apartheid she addressed the UN Assembly on the subject in 1975 and 1976.

Makeba finally returned to South Africa following the release of Nelson Mandela and the end of the apartheid regime. In 1987 she joined Paul Simon on his worldwide Graceland tour. Makeba was among the first African musicians to achieve international acclaim and she has been a role model for other female African singers like Angélique Kidjo.

I recall spending an entire weekend in my London flat listening over and over again to Salif Keita’s mesmerizing voice on the album Mandjou (1984) and I have never tired of hearing it. By then Salif had moved from Mali to Paris where he recorded another stunning album, Soro. Critic Robin Denselow described this remarkable fusion of Western and African traditions as ‘a mix of synthesizers, subtle rhythms, brass and chanting African choruses, all topped up with one of the greatest soul voices to be heard anywhere in the world’.

An albino, Salif Keita hopes for a world of mutual understanding and multiculturalism and to this end he set up the Salif Keita Global Foundation to work for the fair treatment and social integration of people with albinism.

Ali Farka Touré (1939-2006) only left his farm on the banks of the Niger river at Niafunké near Gao in northern Mali to record and tour his music. Indeed he was elected mayor of the town in 2004. I first saw him in concert in London in 1985 and was immediately blown away by his blues guitar and voice and his imposing stage presence.

I came to know him as a gentleman with a huge heart. Among his favorite artists were Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, Otis Redding, Jimmy Cliff and James Brown. When he first heard John Lee and Albert King, Ali swore they must be Malian, so closely did their music relate to his own. His collaboration with the American blues and reggae performer Corey Harris on the album Mississippi to Mali (Rounder Records 2002) further proved his point.

Promoted by the London label World Circuit who released most of his albums, Ali Farka Touré won three Grammy awards, the first in 1995 for Talking Timbuktu, his collaboration with Ry Cooder, the second in 2005 for In the Heart of the Moon, which he recorded with Malian kora player Toumani Diabaté, and posthumously in 2010 for Ali and Toumani.

Your book does a good job of telling the story of the rise of hip-hop in Senegal. What do you see as the future of hip-hop on the African continent?

When I last visited Dakar in February 2020 I was amazed at the energy I observed not only in music but in all areas of artistic endeavor. A whole new generation of bright young people, many of them educated abroad, have returned home to take part in the development of their own country.

I am sure the same is true all over Africa which is developing at a dizzying pace. Six of the world’s ten fastest growing economies are now African. By 2050 around 2.2 billion people could be added to the global population and more than half of that growth will occur in Africa. As elsewhere progress had been held up by the Covid-19 pandemic but Africans are nothing if not resilient.

Senegal’s hip-hop artists both male and female joined forces with Youssou N’Dour to warn of the dangers of the virus in the excellent video ‘Daan Coronavirus’. Burna Boy’s Twice as Tall has just won the Grammy award for Best Global Music Album and Afrobeats are certainly flavor of the moment. Young Africans love to rap and we wait to see who will be the future stars. For the moment I will put my money on Senegal’s Dip Doundou Guiss. Check him out!

You can buy Notes From Africa directly in this link.