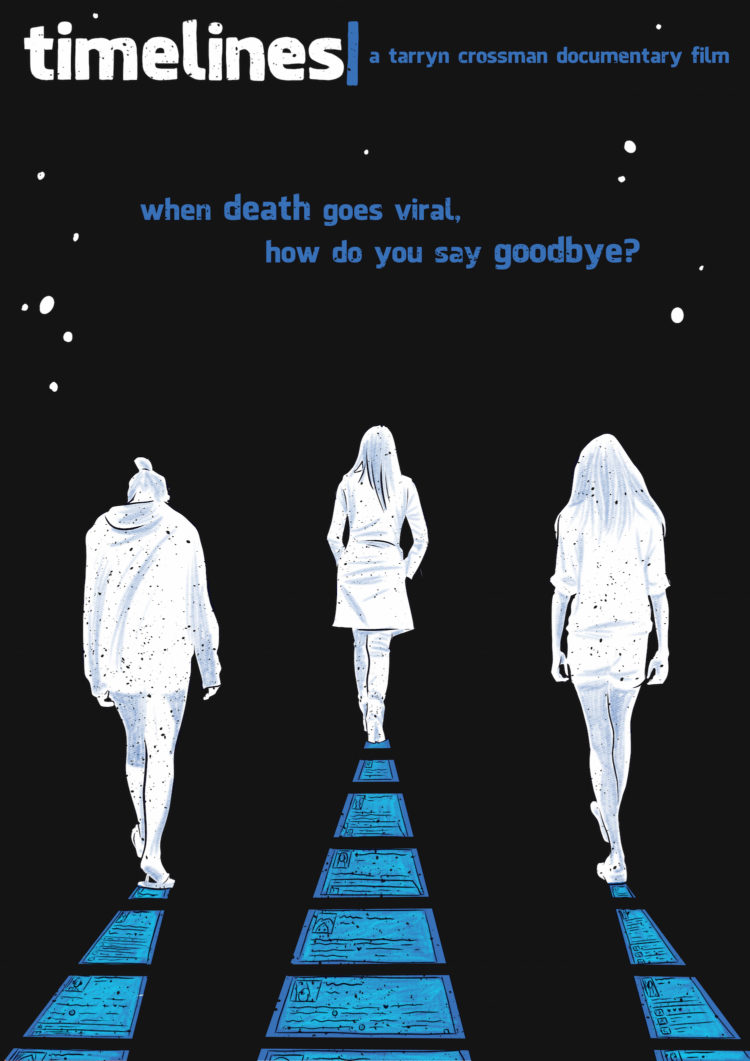

Ahead of the screening of Timelines, her documentary on death and social media, at the Jozi Film Festival, we talked to director Tarryn Crossman about how those left behind deal with the online profiles of their loved ones.

On December 21, 2014, 16-year-old Amber Cornwell from North Carolina in the USA posted ‘If I die tonight, would anyone cry?’ on her Facebook wall. The next morning she was found hanging in her closet. Her parents and friends hold bullies on social media responsible for her death.

South African documentary maker, Tarryn Crossman, never set out to make a film about social media, death and grief; it was initially meant to be uplifting. It’s just before the Durban Film Festival, and I am speaking to her over Skype – suitable given we are talking about online communication.

What happens to your social media presence when you die?

It was Kaileigh Fryer who first sparked her interest. She was a 19-year-old girl from a small town in Australia, who died in a car accident in 2013 and left a bucket list in her journal which was handed out at her funeral. Since then people from across the world accomplished tasks on the list in honour of her memory and posted them on a Facebook wall set up specially. The grief of a small community alchemised into a worldwide phenomenon. This intrigued Crossman enough to go to Australia: ‘Maybe I could make a documentary film about a small-town girl who’s changing the world?’

She flew out with her director of photography. This approach is typical of the filmmaker who has been running her own production company for the last decade and has made films on subjects as varied as the trade in training wild animals in Nigeria and military boot camps for Afrikaaners in South Africa. She initially planned to film a short version of Kaileigh’s story independently and sell a feature off the back of that. But she soon realised that this wouldn’t do the topic justice.

Crossman soon wanted to find out how other families in similar circumstances have been affected. There seemed to be a gulf between the online emotional outpouring and the families’ searing private grief. Her documentary Timelines turned into a sobering look at the effects of a digital footprint on the life and memory of three young women. What happens to your social media presence when you die? The line crackles and fizzes as she collects her thoughts.

‘Those people going to swim with dolphins in the name of Kaileigh; it seems so silly when you see how broken her mother is,’ Crossman says, even though she admits it appears to console some of the family in some way. ‘For her mum, it’s like a life-support system.’

For Crossman, the virtual self may be part of a parallel life but it’s still key to how you are.

While Kaileigh’s mother has embraced her daughter’s online legacy, Amber’s blames her daughter’s virtual life for her death and has shut down her Facebook page. The film is as much about them as it is about their daughters. ‘It was meant to show how the digital era has changed the way we grieve and then the most real story became the grieving stories. Those stories [the mothers’] felt the most genuine.’

Amber’s mother is still angry while her father can barely express his sadness. His sentences tail off as he sits in his makeshift dog grooming parlour in the garage while Amber’s younger sister Breanne helps him silently. She lifts quivering shorn poodles from table to table; nooses, designed to hold their bodies still, hanging empty.

Though absent, the young women still come across powerfully. South African Jenna Lowe is the third to feature in the film. Diagnosed with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension, she launched the #getmeto21 campaign to raise awareness of the need for more organ donors. In the videos she recorded to bear witness to her illness, she comes across as a PR dream – beautiful, articulate, passionate. But Crossman insists that this is how she really was. ‘Jenna was super poised and staged but that’s how she lived her life in real life.’

Some research has suggested that, among teens aged 10 to 14 in South Africa, suicide rates have doubled in the last 15 years.

For Crossman, the virtual self may be part of a parallel life but it’s still key to how you are. ‘So many elements of social media are so superficial, but at the same time they’re not,’ Crossman admits, conceding, ‘They’re so much of who a generation is now. For Amber she was Amber online as much as she was Amber off-line. Those were two realities for her.’

But one reality proved more dangerous than the other. ‘Teenagers always have had angst; they are always depressed, are always trying to prove who has the more emo feelings. It’s now playing out online and that makes it more dangerous. People are more vulnerable to opinions online. If it’s happening offline, it’s your friends; it’s maybe a few strangers at school.’ Studies have indeed shown that those using social media more than two hours a day are more likely to have suicidal thoughts. And it is not first world privilege; some research has suggested that, among teens aged 10 to 14 in South Africa, suicide rates have doubled in the last 15 years.

Amber’s parent have since forbidden Breanne from using social media. But Crossman can’t see how such a blackout is feasible. ‘When we were teenagers we had to figure out who we were – it was a rite of passage – and unfortunately that now means figuring it out on social media. You can’t remove it from their reality. You can only do it by helping them figure out how to do it and not get into shit. How to do it and be as true to themselves as they can. We’re totally at the beginning of it. I don’t really know if I think it’s a terrifying thing or not. People can be so shit and they’re a hundred times worse on social media but it’s going to be part of who we are.’

Everyone owns a piece of you and your memories change, people’s perceptions of you change.

‘We’re still in the beginning stages,’ Crossman reflects, ‘because we still have a generation who think like I do. Amber and her generation don’t think any other way. They don’t have any censorship on what they say or what they put on for the world to say.’

This lack of control persists in death – people morph into someone quite different from who they were. A friend remembers Kaileigh as someone who ‘liked to get pissed and fall over and hurt herself.’ In other words, a real person. Another friend seems almost resentful that Kaileigh’s been reduced to a Facebook page. ‘They’re consuming these girls,’ Crossman seems sympathetic.. ‘Just go skydive if you want to skydive. You don’t need the excuse of a girl’s death.’

‘When all of this is taken out of the personal space, it gets ugly. Everyone owns a piece of you and your memories change, people’s perceptions of you change.’ Hell is other people – and their opinions. But it’s also oddly like nothing has happened; the girls are still there. The messages that Amber’s classmates have left on her Facebook page, banal and trivial, make it seem almost like she hasn’t died: she’s simply moved away or gone on a long voyage.

The documentary – a patchwork of home videos, interviews, fly-on-the-wall shooting and screenshots from social media – is uneasy viewing. Kaileigh’s mother keeps her daughter’s laptop permanently on in the kitchen as if she’s worried that by switching it off she would lose her daughter all over again.

In another scene, she and a friend read out the messages her daughter was sending her on-off boyfriend before she died. In an age where we record all our sentiments, and where digital shrines are built to those who have gone, it seems as if nothing – particularly privacy – is sacred. But in a world where social media has become part of life, it’s not surprising it’s now intricately bound up with death.

Timelines will be showing at the Jozi Film Festival this September (more info here) and at The Bioscope in October.