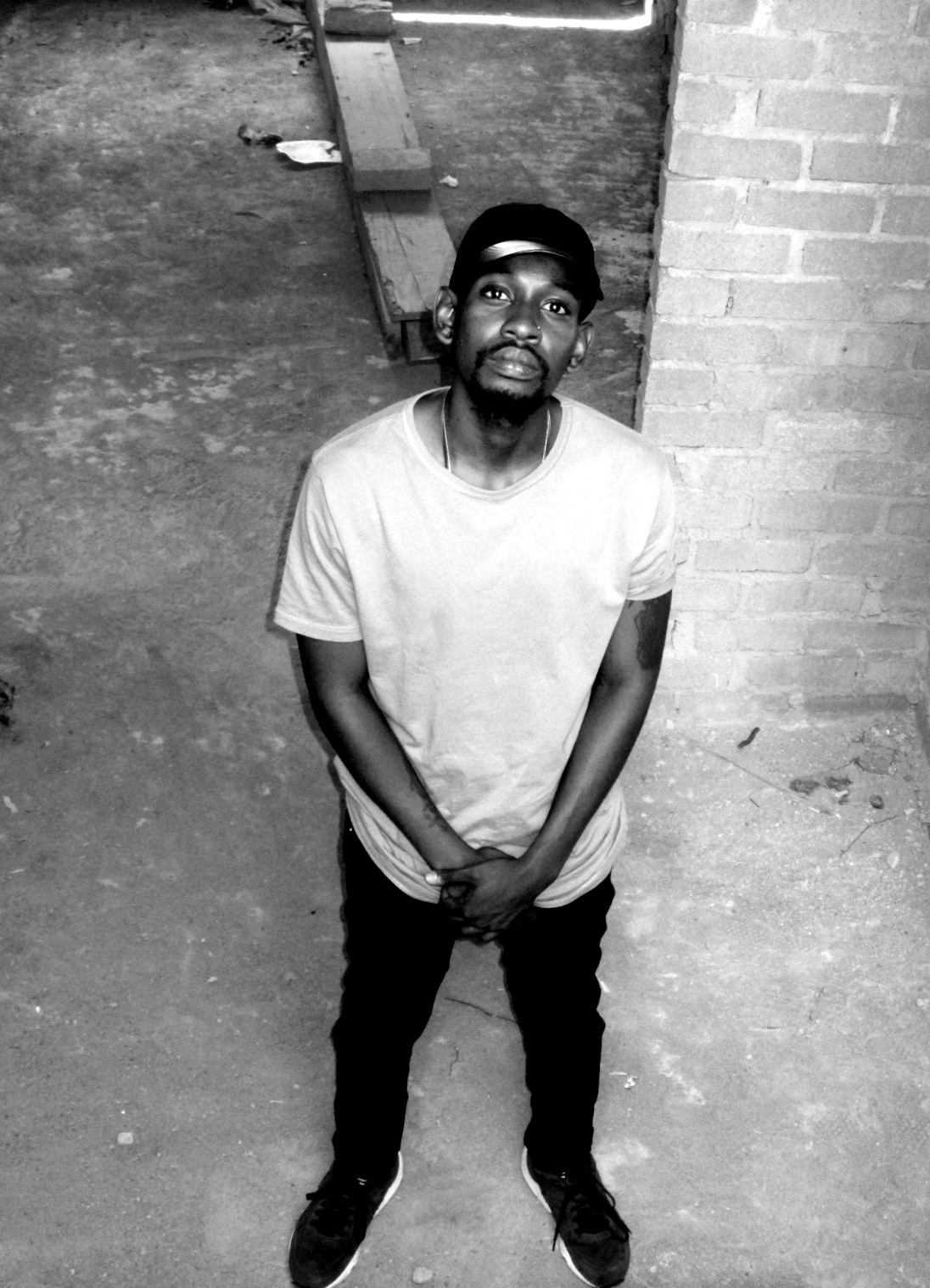

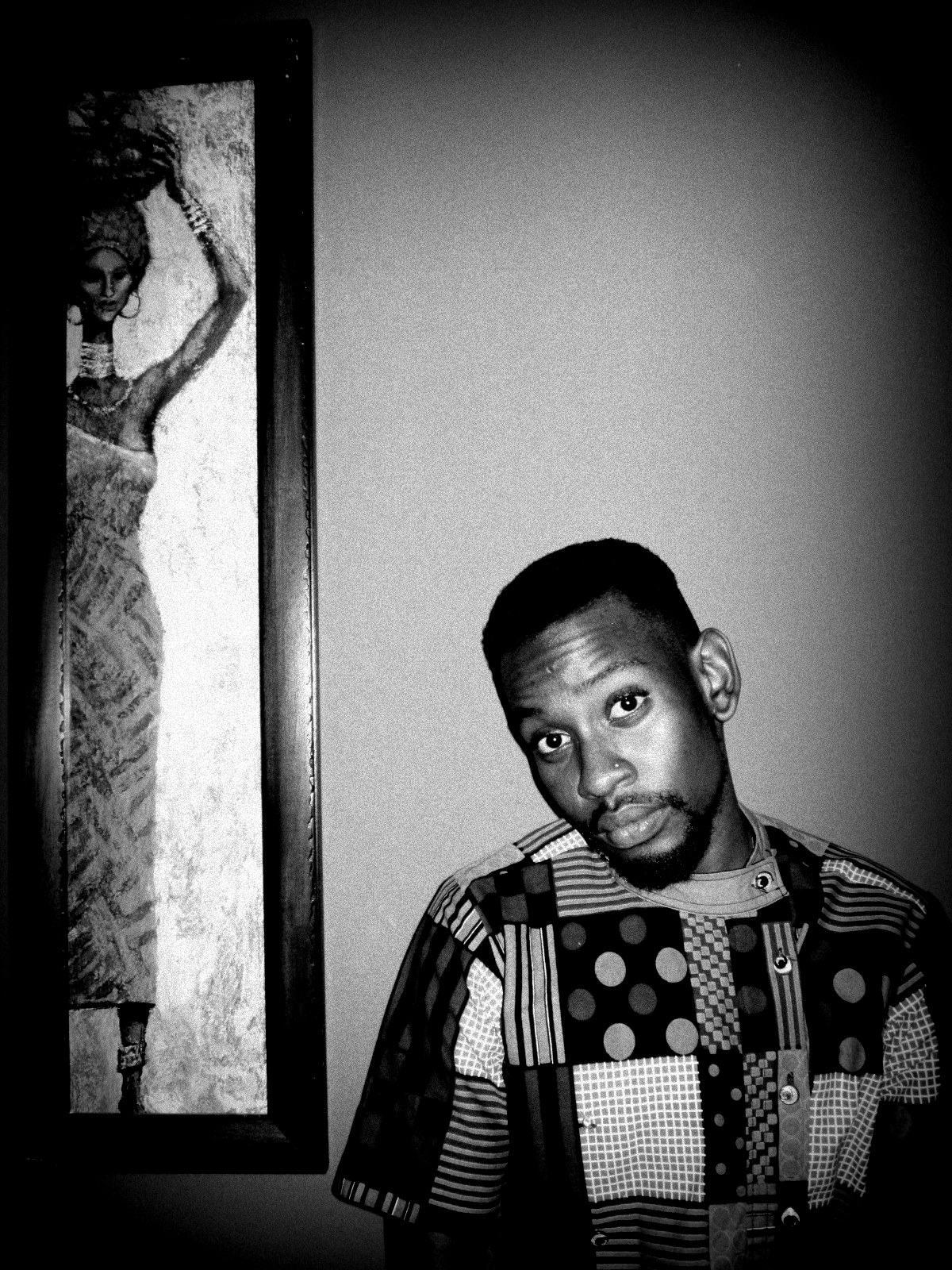

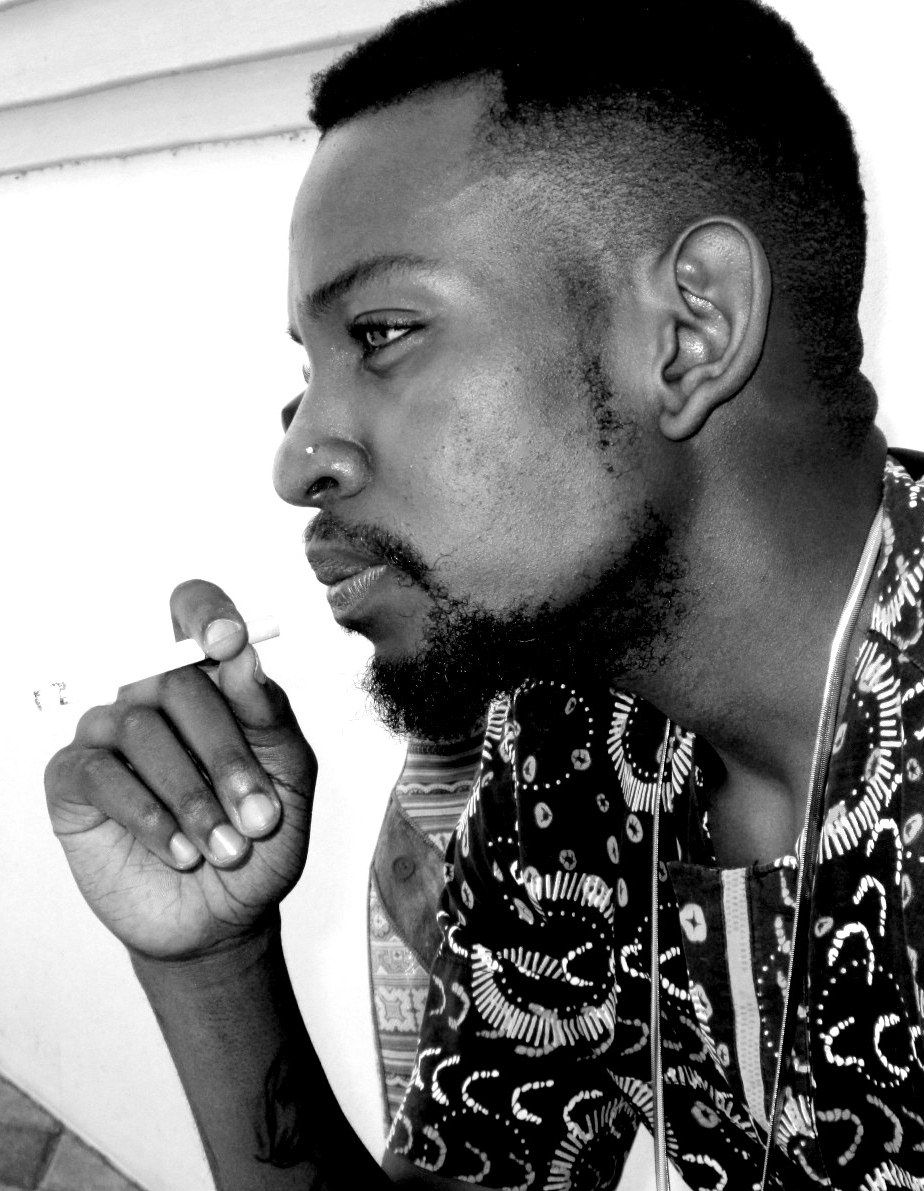

I’m more of a talker than a doer, which is why when I saw one of the most handsome men I’ve ever seen rapping in a two-minute freestyle about a year ago, I decided to try and interview him instead of trying to sleep with him.

Veezo’s a bit of an urban legend in our social circle – the young Tswana rapper who migrated to SA and made everyone who knows him proud by signing to a major label. The fact that this deal didn’t work out doesn’t seem to deter anyone from celebrating it; they’re just happy to know someone who kinda sorta won at life at some point. And the success of his apparel line with long-time friends and collaborators Tshego, Yaw Bannerman and Gordo, VOODOO, only adds to his star quality.

So far I’d never gotten the opportunity to bask in his alleged glory, or be severely underwhelmed by its lack, whichever way things went, but after watching his We Made It freestyle, I knew I’d have to somehow seek him out and put an end to my curiosity once and for all.

After pulling a few strings and managing to finagle my way into his contact list through the help of yet another person who assured me he was ‘a cool guy’, I spoke to him and arranged to meet a man who seemed polite enough (over the phone).

He was on a music video set with Faded Music Group – a bunch of young men who make trap music and scare the parents of teenagers while capturing the hearts of the kids. He appeared and greeted me warmly enough. He was polite and trying to make a good impression and might I add, as gorgeous as ever, and I decided that even if he was boring, his face just might save this interview.

He apologised because he was still shooting and led me out onto the patio while he went back to work promising to be back soon – like I was complaining. I was sitting in one of the grandest houses I’ve ever seen on a music set with beautiful women all around me – he could take as long as he likes, I assured him.

Veezo was born Luvuyo Lejowa some twenty something odd years ago in Johannesburg to his Xhosa mother and Tswana father. His dad, a pilot, wasn’t around much growing up so when his parents decided to split, Luvuyo decided to go with the one parent he felt he knew better and his older sister.

‘The three of us moved into a flat and I watched my mother basically start from scratch. But it was like… We finally felt like a family – just the three of us. It didn’t seem like anything was lacking. She’d go to night school and stuff and I watched her better herself over the years. Now she’s made it and I think I get my desire to make my own life from her.’

‘I actually used to listen to a lot of R’n’B – Donell Jones, Montell Jordan – Those were my people!’

As a child he went to Baobab Primary school in Gaborone and, weirdly enough, listened to a lot of R’n’B.

‘My love for music started at a young age because my sister put me on. I actually used to listen to a lot of R’n’B – Donell Jones, Montell Jordan – Those were my people! I wanted to be like them. I wanted to be an Usher one day or B2K – I even bought a B2K CD.’ And that, ladies and gentlemen, was his first mistake, which inevitably led up to the second – he got cornrows.

‘My mom didn’t try to stop me. She had no say. I saw what I liked and when hip hop was in, when the snapping was in (during the rise of the Crunk genre made famous by Lil Jon and affiliates) I had the huge shirts.’ His love of hip hop only started halfway through primary school when his friend T-Izzy (now a locally famous personality) started rapping. ‘We had a little group called Broadway and I didn’t know I could rhyme or anything but I didn’t want to feel left out… We performed at school shows and stuff but I didn’t think I was that great so I stopped in high school.’

‘My sister went to Gaborone Senior Secondary and she always told me how cocky and shit those kids were and I said yep, that’s the place for me.’

He chose a different high school to his friends: ‘I didn’t want to experience the same old thing so I opted to go to MAP [Maru A Pula]. My sister went to Gaborone Senior Secondary [a government high school close to MAP] and she always told me how cocky and shit those kids were and I said yep, that’s the place for me. I didn’t write any other entrance exam – that school was the only option. So I wrote the entrance exam and got accepted then I went, and that was it.’

It was there that he’d lose, and later regain, the desire to rap.

‘In Form 6 someone approached me and said “Yo, you used to rap and you were pretty good so you should try it out again,” and I was like why not? I’m fucking young, it was fun, I had no worry in the world, I could do that instead of doing my homework. I’d do my work in the morning before I got to school.’

Around that time he did a jingle for radio legend Tumi Ramsden, who was with Yarona FM (the youth’s radio station of choice) at the time, replacing friend and fellow rapper Young Slugz. Award-winning producer Bk Proctor heard the jingle and gave him a beat.

‘We made a pact that we were gonna humble ourselves, move to Joburg the next year, get into school and do music from there.’

The resulting Young and Fresh got a remix with some of Botswana’s most recognised rappers Thato ‘Scar’ Matlhabaphiri and Ralph ‘Stagga’ Williams III and shot to the top of the charts. ‘It felt like that was the shit I’m supposed to do.’

But fate intervened and Luvuyo ended up going to the University of Pretoria to study finance management. He quit pussyfooting with music. ‘My mom wasn’t having it.’ He met Tshego, who had a studio there, and gradually got less interested in school. The World Cup was on too. And he eventually quit finance. ‘We made a pact that we were gonna humble ourselves, move to Joburg the next year, get into school and do music from there cos that was where we needed to be. Joburg is where the music is coming from; it’s where the industry is.’

It happened and Veezo decided to take a gap year to make music before going to AFDA [the South African School of Motion Picture Medium and Live Performance].

‘During the course of my gap year I was making a mixtape called STRES which stood for Success Through Recording Everything Sober and I was sober for a year – no drinking, smoking nothing. It was like fasting. I wasn’t saying I quit, I was taking a break to help me elevate myself. I could come back once I reached it. I recorded that and the last track I recorded on the mixtape was All I do.’

Everyone knew the guy who said ‘I wanna put my dick in Minnie Dlamini’.

All I do, produced by Gordo, would be the single that would propel Veezo just high enough for him to get noticed by listeners and labels alike. Through simple word of mouth and of course, Bluetooth, his throwaway single had gone viral and during his stay in Botswana for the holidays that year, he realised he was kinda sorta becoming a big deal. His friend and then manager Tebogo Morgan gave the track to Metro FM, Y and 5 FM and despite the fact that no one knew exactly who he was or where he was from, everyone knew the guy who said ‘I wanna put my dick in Minnie Dlamini’.

Muthaland reached out and there he’d spend the next two years making his album V.I.S.A (Veezo Is So Ahead). But the album was never to see the light of day and his relationship with the label turned sour. ‘ I wasn’t out there like I should have been. I felt stagnant so I left. I had to take another year to regroup and re-evaluate who I wanted to become. That’s when I made the We Made It freestyle.’

It’s clearly about some shit he’d obviously had on his chest for a while. ‘I felt used and abused,’ he said, ‘I felt like I needed to say watch out. The industry is messed up.’ It was a manifesto, the rising of a phoenix. Every verse since then has served as a fanning of feathers, a slow but steady transition, and reintroduction to a more refined, more mature creature: Veezo the Visionary.

‘Tshego’s actually the one who told me… He said a lot of people wait to be given a lot of shit by labels or whatever, but there’s no reason why you shouldn’t do it yourself. You have to take it!’

Since then, Veezo has only worked with a close-knit group of people. From Botswana’s Ozi F Teddy to South African veteran DJ Ready D, he’s shared bars with the best of them – but none as consistently as with Botswana’s Faded Gang. The group is notorious for their uncompromising nature when it comes to well, pretty much everything. They work alone, party alone, collaborate amongst themselves and give props to only a select few.

‘Those guys are dreamers. And I’m a dreamer too.’

‘They’re my motherfucking niggas,’ He said, making sure to stress every syllable on the last half of his sentence. ‘They make me part of family every time I see them. I believe in them because they believe in themselves. The energy they put out rubs off. You can’t be a failure around them, they exude crazy energy and the music is quality. I like that they take the time to mix songs and make sure it sounds right. Those guys are dreamers. And I’m a dreamer too.’

But despite a now apparently cordial relationship, Muthaland went ahead and released an album of some of Veezo’s old tracks. Despite him apparently signing whatever music he made under them over to them when joining them, he was visibly angered by the fact that no one had even so much as contacted him to let him know it would happen. ‘That wasn’t even my best!’ he said. Whatever shady things happened, he’s mostly angry that they put his name on material that isn’t as good as he knows he is.

So what is Veezo’s best?

V.I.S.A will apparently host ten or thirteen tracks, depending on what time of day you ask Veezo, and as yet does not have a release date. ‘I’m a perfectionist so I want to get everything just right. I think even up til I’m set to release it I’ll still be editing and shit. I want everything to be just right.’

Sure, he’s been working for all these years but putting time into something doesn’t automatically make it good, so I’m still sceptical.

The first song he played me, Down, produced by Faded Gang’s OBVDO, features Veezo at his best, casually talking his shit. He quickly switches to Free At Last, which he tells me he’s considering making the opening interlude, on which he gets very personal and directly addresses his mother in a typical ‘I appreciate you and your sacrifices’ flow that thaws even my cold heart. ‘I sent it to her at three AM when I’d done it. I just couldn’t wait,’ he tells me.

‘Did she cry?’ I asked.

‘She cried.’

Next is Vumani produced by Gobbla. ‘When you go to a sangoma (traditional healer) in my culture, you’ll do what you do or whatever and there’ll come a time when the healer will say “Vumani bo?” And you’re supposed to say “Siya vuma”. It’s basically saying you agreed with and hear your ancestors. I’ve heard my calling and this is me saying I accept it.’

+267 is produced by and featuring Tshego. It’s an homage to Botswana and an invitation to the listener to keep grinding. ‘Botswana supported me before anyone else did. I can’t ever forget that. They love me here’ Veezo said, obviously humbled.

Tshego is also featured on Dlala, a track which samples the legendary Trompies’ Dlala Mapantsula, and VOODOO, a ballad I fell in love with from the opening Anchorman 2 skit, about love making and all things intimate. It’s not yet finished, and there’s no guarantee that it will make the cut, but the promise of what it could do for him, and to the male fans who’ll use it to woo female fans who’ll no doubt picture his face on their suitors, jolts me upright. It’s beautifully raunchy, so raunchy in fact; we never quite manage to play it the whole way through.

‘So what do you think?’ He asks me.

His eyes lit up when he realised he’d gotten something right.

The entire time he played me his music, he sat in the chair next to me, rapping along to every verse of every song, delivering every punch line gleefully and completely absorbed in what he’s created. His brow furrowed at parts he felt could be better; his eyes lit up when he realised he’d gotten something right. It was evident that he is proud of himself, and yet he still wanted to know what I thought.

‘This will make up for everything,’ I tell him. And I believe that too.

V.I.S.A sounds like years of hard work and dedication. It sounds like growth – a process, a story, and the more I think about his lyrics and presentation of the project the more I realise that although we’ll receive it, the project isn’t really about us at all. V.I.S.A is, mainly for two people.

It’s the painting that gets stuck to the fridge, the passport photo in the wallet, the medal handed out at prize giving: a thing others bear witness to and appreciate but which is really a source of pride between a parent and a child.

And it’s no longer about proving to us that he can rap. He’s done that already. It’s about proving it to himself.

Siya vuma.

Listen to Veezo’s latest freestyle:

Check out more here

Follow Veezo on Twitter @VeezoView