The nondescript house on the corner of Rue 652 in Bamako’s N’Tomikorobougou district is the place where Toumani Diabaté, a master of the kora, spends many of his afternoons.

It’s not the house where he lives, but it certainly is a place where he relaxes, and finds inspiration. He lives with his children and first wife in another house, in another neighbourhood, but this house, built around a small courtyard, is the place his second wife calls home.

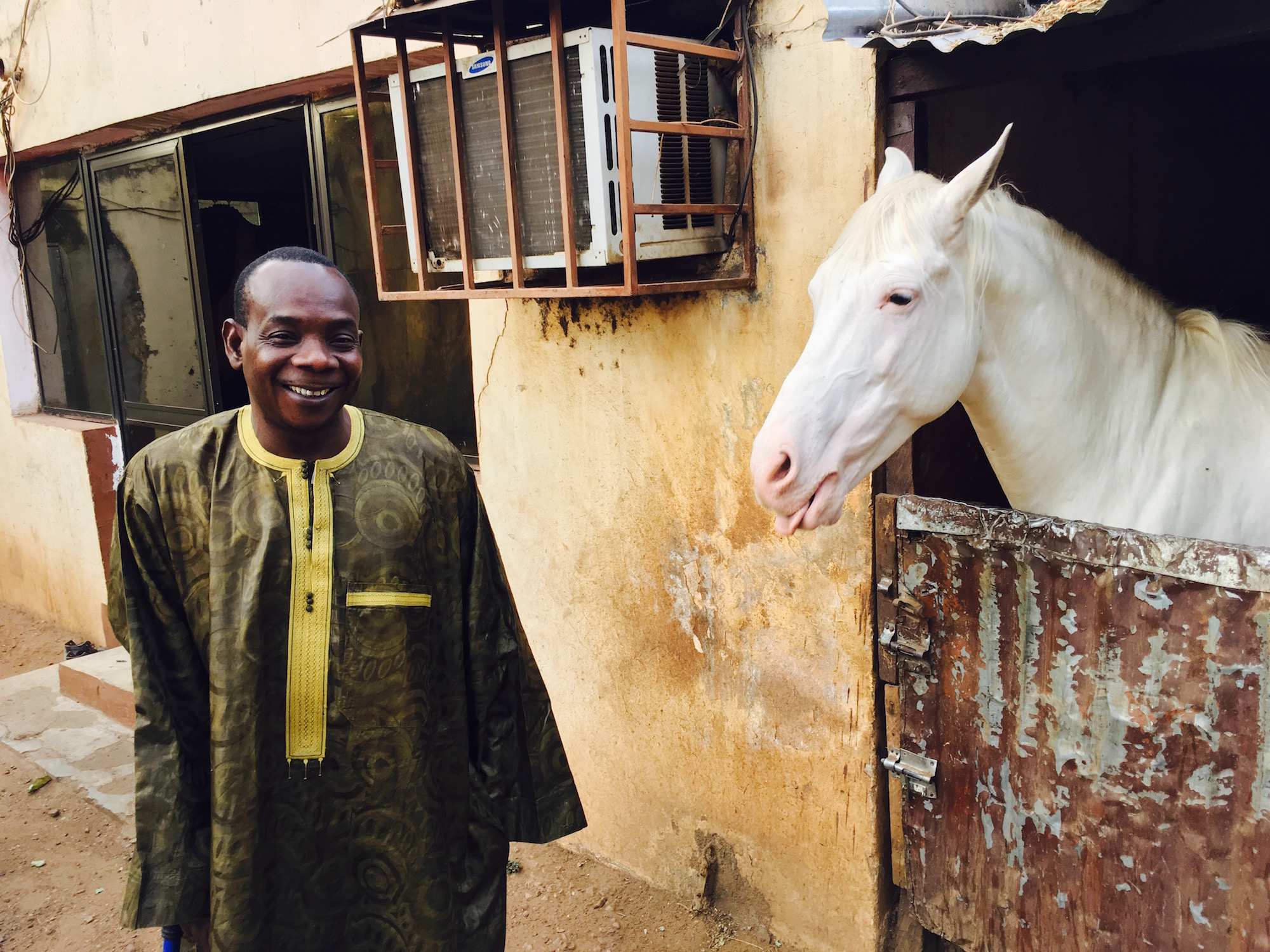

Fily Diabaté, his charmer of a white horse, is very much a part of the family.

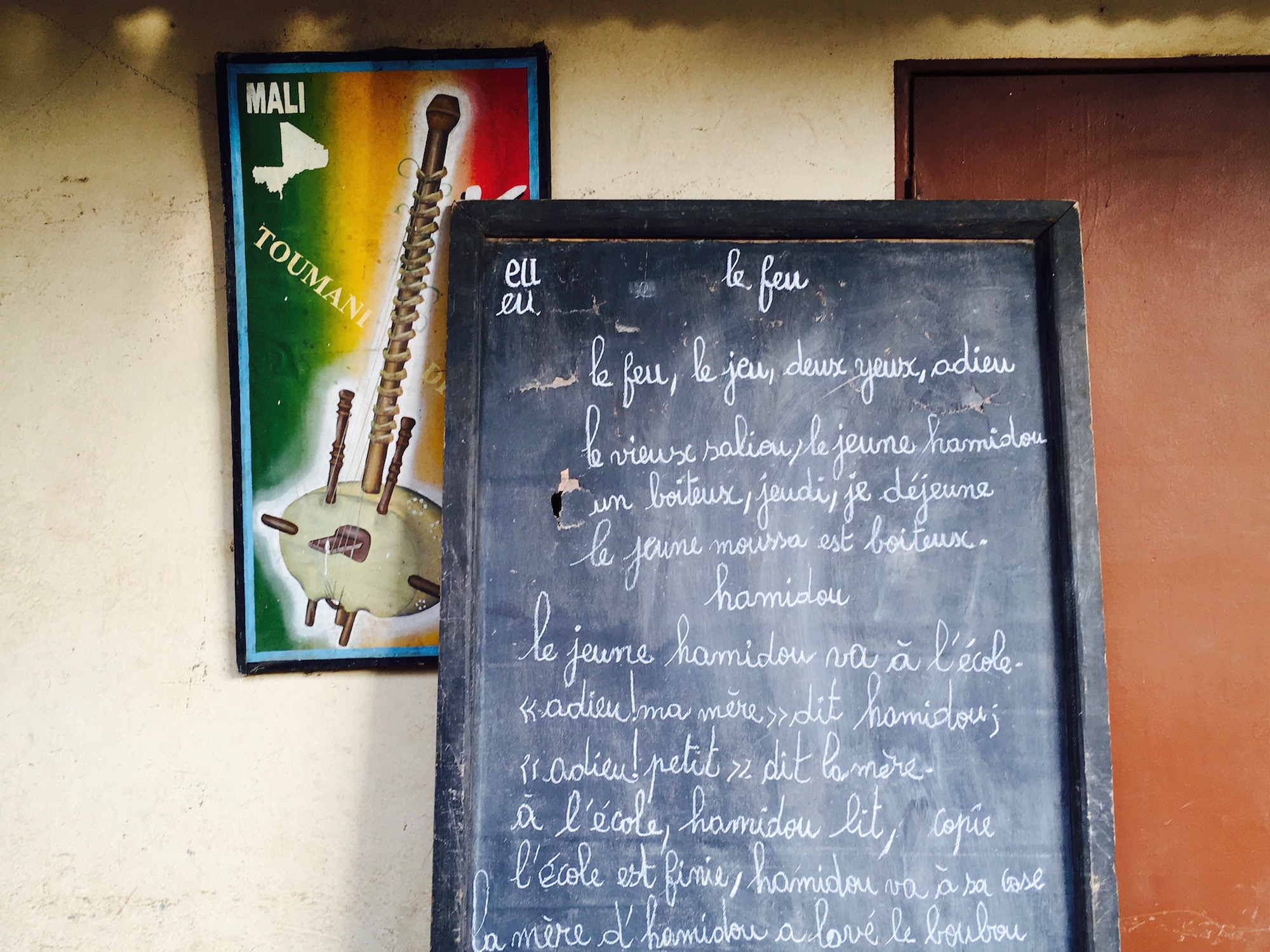

When I visited Diabaté in that house in late February, I noticed that it contains a small artist’s residency, and several classrooms, where the master continues to give kora lessons to students coming from all over the world. Fily Diabaté, his charmer of a white horse, is very much a part of the family, and everyone seems to associate Fily with good luck and longevity.

Many of Diabaté’s stories relate to the kora, to the tradition of the instrument, and to the glory days of the Mandinka Empire, which stretched across ten West African countries some seven centuries ago. Diabaté is probably the best known practitioner of the kora, a 21-string lute-bridge-harp that many people associate with the Mandinka people, and their very spiritual brand of musical entertainment. Kaira, his 1989 debut was the first solo kora album to be released, and he has collaborated with musicians including Tiken Jah Fakoly and Björk.

Even though Diabaté was the first kora player to win a Grammy, he says he is not interested in becoming more famous than he already is.

Toumani Diabaté taught himself to play the kora as a young boy. ‘It’s not as if I ever had more talent that anyone else,’ he told me. ‘In my case, it’s just a story of sharing, and passing on the knowledge, from father to son, from generation to generation. I am the 71st generation kora player in my own family, and my son (Sidiki Diabaté) is the 72nd generation. In fact, we are a dynasty, and this hasn’t stopped for 700 years.’

Even though Diabaté was the first kora player to win a Grammy, he says he is not interested in becoming more famous than he already is. Rather, he wants to reveal some of the mysteries around the kora, and what it means for his people. He invited comparisons to the n’goni, another West African string instrument, which is also made of calabash with dried animal skin. The n’goni looks like a small guitar, and seems more appropriate for faster melodies.

He spoke of similar traditional instruments in the Maghreb and the Middle East, but when describing the leather tuning rings and notched bridge and playing strings in the kora his eyes begin to shine. He says the kora is an instrument that can only be found in the Mandinka Empire, and the way he demonstrates the fingers gripping the two vertical hand posts, you get that all 21 strings are deeply meaningful to him.

Diabaté says that the complexity of his instrument forces a form of humility, because all the nuances speak to the power of God.

’21 equals three time seven,’ he says. ‘Seven for the past, seven for the present, and seven for the future. Why seven? Now, we are getting deeper into the meaning. Seven for the seven days of the week, and also for the seven skies in the Quran. And when we play, we know that the distance between the different skies is the same, we know that the walk from the first sky to the second sky takes 500 years. One needs to walk day and night, non stop, for 500 years, to get from one sky to the next. And the beauty of it all, the power of God is that it doesn’t actually stop at seven. This instrument goes beyond, way beyond, and the same symbolism can be found on earth.’

Diabaté says that the complexity of his instrument forces a form of humility, because all the nuances speak to the power of God. ‘I would love to publish books, and make movies about the kora, because we Africans should be proud of our history, of the symbolism. Damon Albarn, when he came here to perform at the Bamako acoustic music festival earlier this year, he brought a British instrument from the 16th Century, but Africans have a lot to be proud of, as well. I have toured the world so many times, but this kora is something special that we Africans have, that we should be proud to have.’

The Diabaté family has only ever known two things, the kora and the Quran.

Diabaté says that, among his most prized possessions, is an old kora made from thin strips of antelope skin, and one of the pleasures in his life is seeing the artisans at work in that house, when they cover the calabash with the cow skin which is then supported by two handles. ‘The Diabaté family has only ever known two things, the kora and the Quran. I created a chart for the kora. It’s called the Toumani Chart, because it’s in my blood. I am a griot, which means that I was born a griot. One doesn’t and cannot become a griot. You have to be born into the caste.’

Griots are West African storytellers who are the revered custodians of oral traditions, which they apply, often in music and dance, to interpretations of current events and everyday situations. Diabaté, who is 50, says that ‘there are certain things that one cannot understand until one turns 40, and there are other things one cannot understand until one turns 60. We griots are living archives, and memories are what we focus on.

We are the lifeblood of our societies.

‘In our Mandinka language, we are actually called jaly, not griots. That word jaly means blood. So there you have it: we are the lifeblood of our societies.’

What, I asked him, has he learnt from his life as a jaly/griot? The answer came easily.

‘In life, one is always in the middle. There are people who are stronger than you, and there are people who are weaker than you. As a believer, that is very important to me. Some people get stuck where they are, because they think they know everything, and others because they don’t know enough. Africa has always been about culture, which is why we owe it to ourselves, and to future generations, to open up and share our traditions with foreigners. Everyone needs to learn from everyone.’