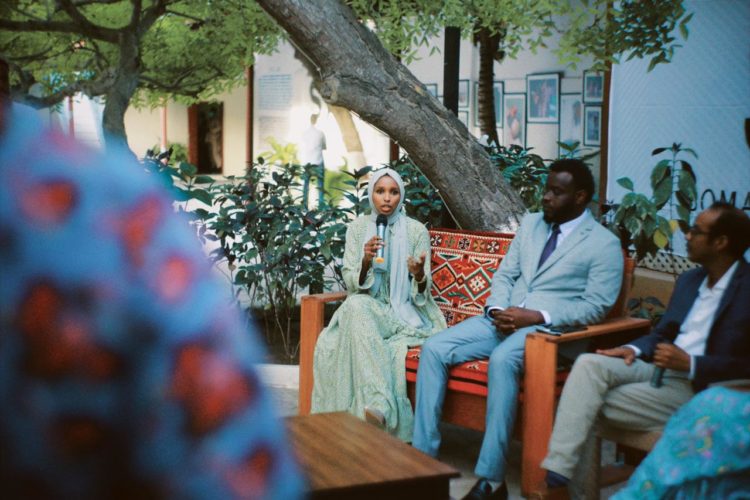

Most people know Somalia for its decades-long civil war. As a result of the conflict and instability, many citizens are living outside of the country. Sagal Ali is part of the two million diaspora. Unlike others who sit back and complain about how things are “back home”, she has chosen to get involved in a different kind of effort to rebuild her home country.

Ali’s weapon is art, and her vehicle is the Somali Arts Foundation (SAF), the first contemporary art institution in Somalia. Based in Mogadishu, SAF aims to increase public enjoyment and understanding of contemporary art. Ali wants to use art to help build a more peaceful, prosperous and harmonious society in a country that is often labelled a failed state.

Ali feels that scars in a country last long after the conflict is over. Civil war is known for disrupting the collective memory of a society and rupturing the idea of community. It exacerbates divisions and feelings of “us against them”. Conflicts, like the one which tore through Somalia, have a tendency to destroy social contracts. Without these, trust inevitably breaks down.

“Art after conflict creates a unique opportunity to express the pain of loss and war, to share the burden, and to potentially begin to heal from it,” she says. “Many forms of art can circumnavigate cultural and language differences. There are many examples around the world where campaigns to reduce violence and support recovery after conflict have used a variety of approaches, including theatre, music, visual art, and poetry. Such efforts can address feelings of fear, mourning and mistrust that people experience.

Art, at its best, can offer spaces to dream

“At the same time, they can also show the need for justice, hope for a shared future, and efforts which seek to break down stereotypes, thereby encouraging empathy in opposing groups, which is essential to building bridges after conflict.”

Ali sees art as a means to allow people to examine their environment, to critically engage with it, to question and challenge it, while carving out spaces to imagine better futures. She insists that art, at its best, can offer spaces to dream, and enact real change in society.

“Contemporary art in particular can be a path to interrogating Somalia’s recent traumatic past,” she adds, “while serving as a channel for enquiries into present day-to-day life.”

Many of the most influential Somalis are now living in the diaspora, mostly in Europe and America. As she looks to shape peace with different kinds of Somalis, Ali is counting on the Somali diaspora to help the country heal through creative expression. The Somali diaspora is known for playing a central role in political and economic affairs, and its socio-cultural impact inside Somalia is undeniable.

“For many Somalis in the diaspora, in particular young Somalis, life can be driven by a translational ethos. It’s that intersection between feelings of belonging to ‘Somalia’ as a ‘homeland’ and practices of citizenship abroad, mostly in Europe and North America. This transnational identity, I believe, allows Somalis in the diaspora to compare contexts and this comparison may lead to contestations about Somalia’s future for the better.”

She mentions that art and culture have been completely absent from the education system in Somalia since the civil war broke out. With the collapse of government, the education system was taken over by private entities and individuals, who sought to profit from it. As such, the creative industries lagged behind, because only sectors considered ‘traditionally employable’, such as medicine, engineering and teaching took precedence.

In making her case for art as a weapon, she points to the fact that arts-based methods have been proven to reduce reliance on verbal communication, which make them particularly useful for exploring sensitive and controversial topics. Those topics can often be difficult to articulate verbally. Because of that, Ali believes that creatives in the Somali diaspora can “leverage the education, training, and resources they were able to acquire elsewhere to support contemporary arts in Somalia”.

If she is able to achieve critical mass in her effort to enlist enough creative thinkers and doers, the Somali Arts Foundation will surely lend legitimacy to the efficacy of art for trauma-healing purposes.

With thanks to Africa No Filter who made the #Limitless series possible.