I am not really the Isaac-Newton type, or those Indiana-Jones adventurous guys who explore dark caves in search of bones of a civilisation past and call their findings Homo naledi. I’m more programmed for art and leisure.

But I heard about Eugene on the BBC when Mathew Bannister interviewed him on Outlook, one of my favourite radio shows. I am a human story kind of person. I like journalism that gets to the very nature of humanity and for me, Outlook resonates.

Eugene’s story got to me. He builds these incredible rockets in his spare time. So I found him on FB; wrote him a line; and days later he responded. We met over fish and Ugali severally and thereafter it became a painless routine of beer and bar banter about femmes who wear yellow wigs with overdone make up and why Jesus hasn’t come while everybody who’s acting like a yo-yo claim to follow him.

Deep down, the bloke’s a humble nerd.

Compared to me, Eugene is more of the scientific herd. Although you wouldn’t know it. With a mop of dark short hair, strong arms, a gait of a man who’s ill at ease with himself, 27-year-old Eugene Awimbo can easily pass for an average guy. But when you look in his eyes, he can effortlessly squint with the avid concern of a Darwinian devotee and equally come off as a curious Ivy-League aficionado who lulls with big terms like ‘astrophysics’ etc.

Deep down, the bloke’s a humble nerd. Smiles courteously, funny, ambitious, creative and a good father to a two-month son called Arnold.

It was back in 2007, that Eugene got inspired to develop his own rocket after watching a documentary on National Geographic Channel.

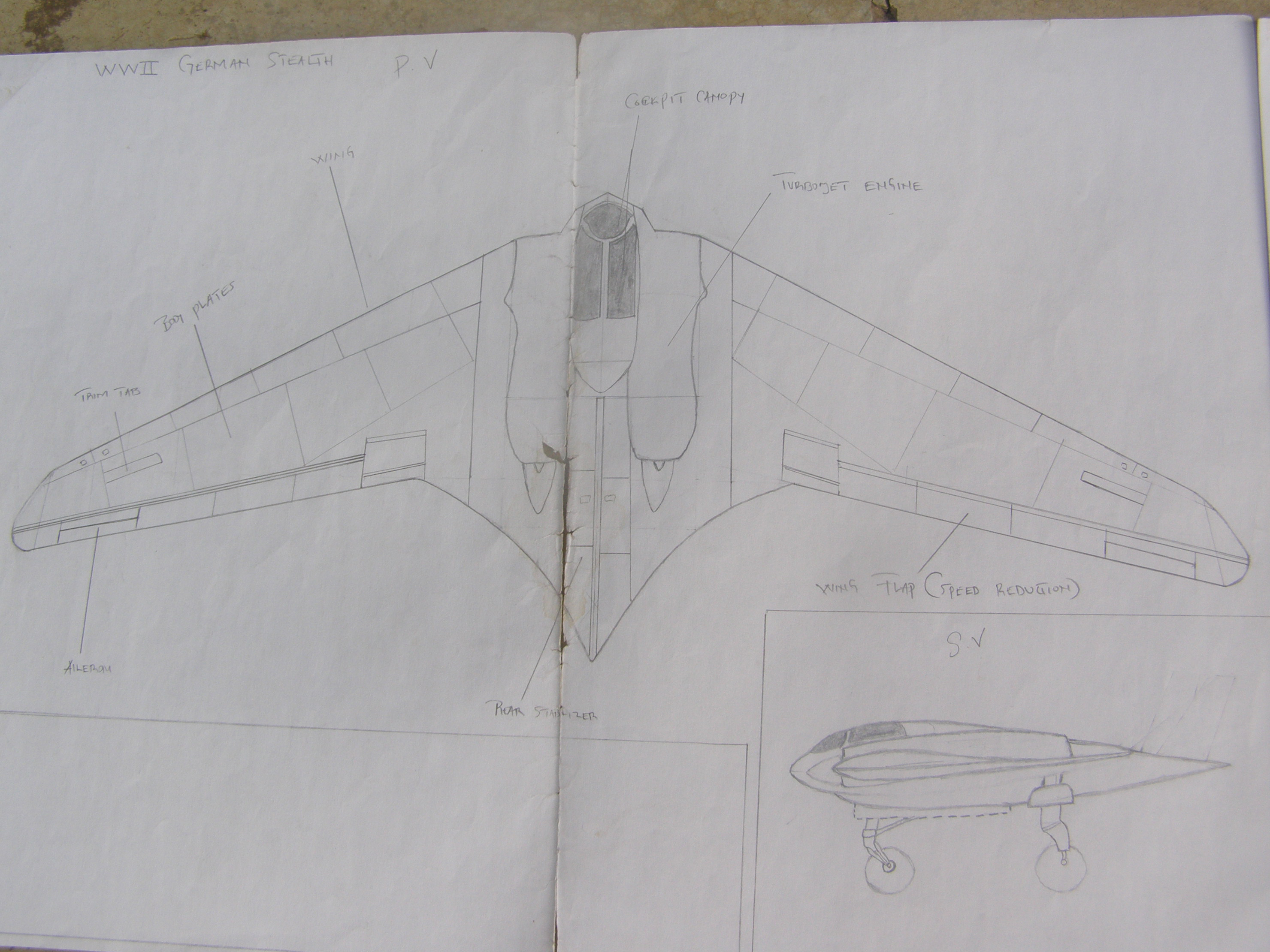

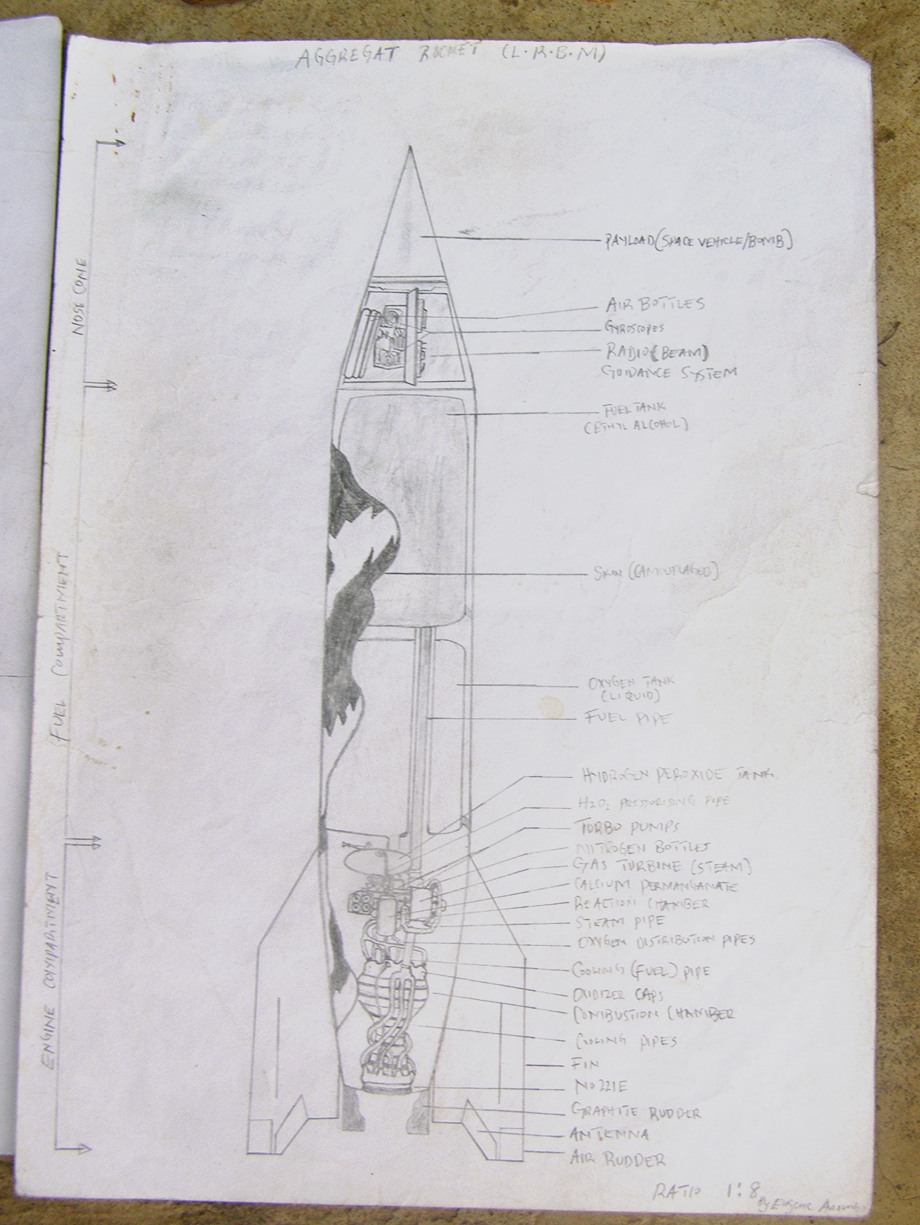

‘I got carried away and more so thrilled by how the German engineers developed some of the best aircrafts of their time,’ Eugene enthuses. ‘These are my reservoirs of inspiration; people like Werner Von Braun are the rocket engineers that motivate me and also engineers like Willy Messerschmitt, Heinkel, Junkers, The Horten Brothers, Fieseler Storch and Eugen Sänger.’

They talk cryptically at measured intervals about dead rocket scientists like Kurt Tank and Arthur Rudolph, men who pioneered the art of rocket science in 19th-century Europe.

One visit I meet Eugene’s wife Judy Apome. She’s this funny, big-hearted woman, who loves her man to boot and knows how to take care of him and Arnold.

When you see them playfully together, teasing each other, you won’t really take long to note there’s something else that binds them together, apart from their love for each other and the baby.

They both have a thing for science; they talk cryptically at measured intervals about dead rocket scientists like Kurt Tank and Arthur Rudolph, men who pioneered the art of rocket science in 19th-century Europe.

Life has not been easy for him. When he was eleven, his parents died. His father, a clergyman was traveling to Nairobi from Kisumu, a city in western Kenya for a meeting with Eugene’s mother when his car veered off the track and plunged into a ditch. He was rushed to the hospital but succumbed to death days later. His mother sustained injuries but was overwhelmed by trauma. Distressed by her husband’s demise, she became ill with ulcers and passed on a month later.

Eugene, a third born in a family of five was left alone. The world around him had instantaneously changed; it became a lonely enclave.

He talked to me about his childhood, which was hard. Typical for any child who’s lost his parents:

‘We had to find a way to provide for ourselves by working at that young age. It was one of the hardest experiences in my life. I don’t like going back to that period because everything in our lives came to a standstill; that’s not really a good thing to go back to’.

He launched his first rocket in 2009; it was able to go 200 metres above the ground.

Eugene and his siblings were taken in by their aunt, and for a while things seem to be normal, but this did not last.

‘She tried her best to provide for us but it did not last because it was overwhelming financially and psychologically on her. We therefore had to fend entirely for ourselves, so during the school holidays we did work and actually use the money to pay for our school fees’.

Eugene sits bossily in his dedicated chair and his wife dutifully serves him their favourite meal of Pilau; a spicy mixture of rice, meat and garlic served with raw sliced pieces of tomatoes and onions.

As we rest after the lunch, he extends me a collection of pictures taken in 2009, when he launched his first rocket that was able to go 200 metres above the ground.

He says, ‘The technical part was eventually a challenge but as time went by it got simpler but it takes a lot of time to craft something that can go up. I have to use some chemical compounds; I have to be knowledgeable of the electrical wiring of the rocket; and also take care of the propulsion system that will make it – in the actual sense – go up’.

A self-taught engineer through YouTube, Wikipedia and Wikihow, he uses carton surfaces to create the outer parts of the rocket after he has carefully designed it on paper and then to harden the outer layer, he sprays it with resin.

In 2014, Eugene was invited by Kuona Trust, a local non-governmental organisation which empowers creative youth in the country by showcasing their talents to donors and funders. In front of thousands of spectators he was able to launch his rocket to the awe and wonder of the curious onlookers.

‘That was overwhelmingly exciting,’ he quips. ‘I was nervous but at the same time eager to stand in front of a lot of people and showcase my talent’.

They are charging him with unlawful intent to launch a rocket without permit and possession of other uncertified chemical material.

We planned at lunch to film his next launch. But on the day that I was to drag my crew to our rendezvous spot, I got a call early morning from Judy telling me that the rocket man had been halted that morning with men bearing arms and in a land cruiser wailing wiu wiu wiu.

His curious adventure to lift off the rocket spooked the Kenyan government and they had him arrested on the day my crew and I had scheduled to launch it. He was charged for wanting to launch a rocket without an aviation permit.

‘They yanked him into the land cruiser and took him to Kibera law courts,’ Judy told me calmly. ‘Today they are charging him with unlawful intent to launch a rocket without permit and possession of other uncertified chemical material.’

Eugene spent a night in jail. We eventually persuaded the police to let him go. He was fined 50,000 Kenyan shillings (about US$500). When he left the hell hole, Eugene was traumatised but equally relieved.

‘Sad, really, that I am getting punished for pursuing my craft and there’s millions of corrupt individuals who walk scot free in our streets’

He tells me, ‘Sam, don’t ever wish to be arrested by the NIS (National Intelligence Service), it’s not even the ordeal of the arrest itself, but the very act of spending a night in jail with every sort of gang banger.

‘It was a nightmare,’ he laments. ‘Sad, really, that I am getting punished for pursuing my craft and there’s millions of corrupt individuals who walk scot free in our streets’.

Eugene is no crook; he works as an aquarium maker and designs ponds to earn a living and it’s through the monies that he gets from these businesses that he finances his passion for making rockets. But not enough to buy permits too.

‘It’s really a challenge because, I have no other source of income apart from these jobs that I do, creating toys for kids, or aircraft models for people who sometimes take ages to pay’.

I saw him again afterwards. We’re still thinking about filming the launch; filming that beautiful man-made miracle as it flies into the sky. It will happen once he can find the money for the aviation permit the authorities so desperately want. He regales me about how he aspires to provide affordable transport for Kenyans in the near future with his advanced-pulley-pedal glider and about his hope to develop an aircraft that uses green energy built with environmentally friendly material.

‘Africa has a great potential. We just need to have vocational training schools that will equip children from the formative ages and allow them to nurture their talents while they are young so that they can fully embrace their passion and creative ability without getting pumped with a lot of knowledge that will not help them in their future’.

As we wind up our interview, he plugs in a Keane CD into the computer and lulls us into Nothing in my Way as it blasts through the zinc walls. I am nostalgically nudged ten years back when attending Rock Nite at Carnivore Club was my weekly religious practice.

He continues, ‘If only we could make things happen for the youth by easing obstacles like … oh one should have fifteen years’ experience; oh one should have a university degree… blah blah’.

He enthuses. ‘These makes it difficult for the talented underprivileged kid who lives in the village and yearns to become something in the society… to dream. It reminds me of that line in Shakespeare’s sonnet where he says, ‘For we which now behold these present days, have eyes to wonder, but lack tongues to praise’. That’s how I feel about leadership in Africa’.

With that, my cameraman and I pack and off we head back to the office, but at the back of my mind, I gather Eugene and I have transacted a relationship that’ll last as long as his ambition to make rockets remains in the nerdy crypts of his strikingly big and ambitious heart. Probably in years to come his journey will be worth telling to my grand children. It’s just a case of him launching that rocket while I’m watching.

We’ll let you know about Eugene’s next steps; so keep an eye out for part two.