For someone who does much of her work online, it’s weird that Tabita Rezaire is so worried about the internet. We are speaking over Skype and the voice of the Guyanese and Danish digital artist is muffled.

‘I put a little tape on my speaker and my camera so people can’t spy on me,’ she says in a French accent, still thick. ‘I don’t want to contribute to that system that allows for the exploitation of my words, or my image, or my intimacy.’

I joke that I quite like the idea of a group of 25 or so naked potbellied Russian men glued to the screen watching me watching some rubbish on Netflix (my fantasies are nothing if not vivid). ‘You should mind, because whatever you say is going to be used against you at some point,’ she tells me seriously, then puts on some red lipstick as she looks at the screen. By whom? I ask. ‘The reptilians’.

When you’re disempowered, you’re not confident in yourself and what you want. You can be controlled.

This is a peek into the world of the Johannesburg-based ‘new media artist, intersectional preacher, health practitioner, tech-politics researcher and Kemetic/Kundalini Yoga teacher’ (says her bio) Tabita Rezaire. After attending the opening of her show Exotic Trade at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg, who represent the likes of Yinka Shonibare, The Brother Moves On, William Kentridge, she is in Boston, picking up her Amazon deliveries from her partner’s place, before leaving for New York City. ‘I have performances, meetings, and people to see. My whole internet life is coming to life.’

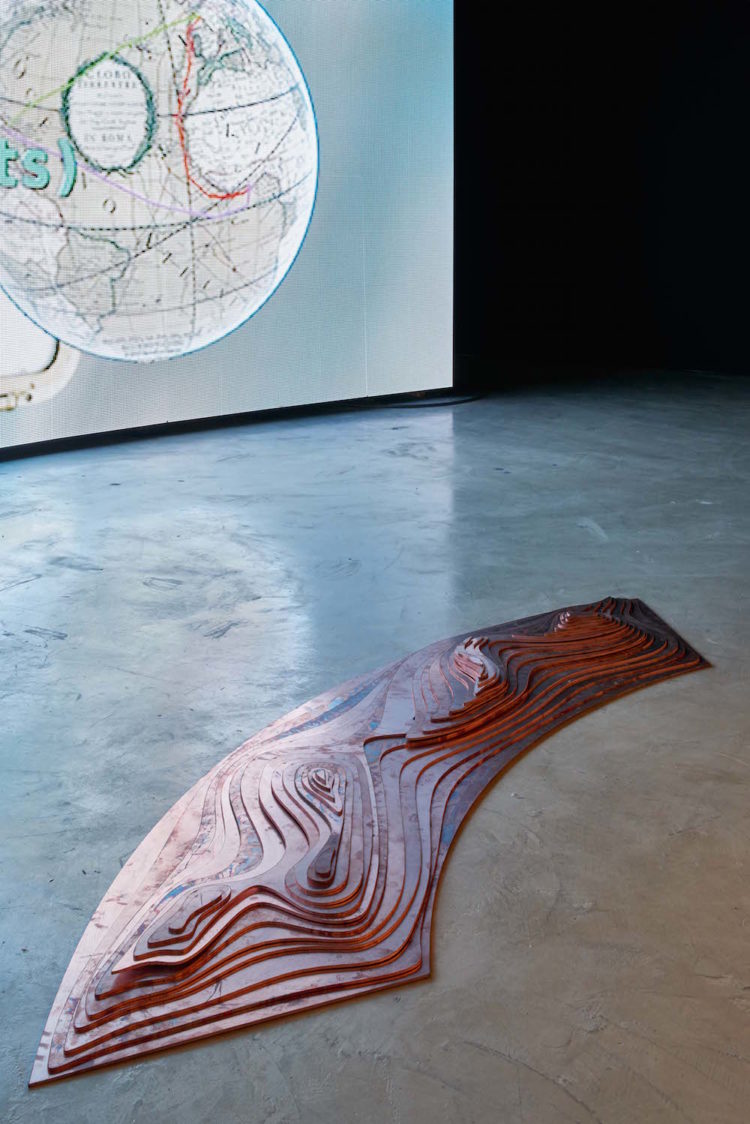

The exhibition has been in the works for over two years. It features six video installations, soundscapes, as well as the self-portraits series Inner Fire. Inspired in part by her MA at Central St Martins in London, she explains that the show is ‘about systems of information and communication. It’s about portals.’

These are what she considers gateways to ecstasy – where ‘the erotic, the politic, the spiritual merge altogether … It’s the merging of all states of being, all planes of being into an acute awareness of your deepest self’.

In another world, she could have gone into banking. She did an economics degree at one of the more elite Paris universities ‘for all the wrong reasons. I got very depressed. Yeah…’

She takes a sip of her rooibos tea. ‘I committed to understanding where my pains came from. When you embark on that journey, you realise that everything around you was designed that way because it benefits the societies we’re in. When you’re disempowered, you’re not confident in yourself and what you want. You can be controlled.’

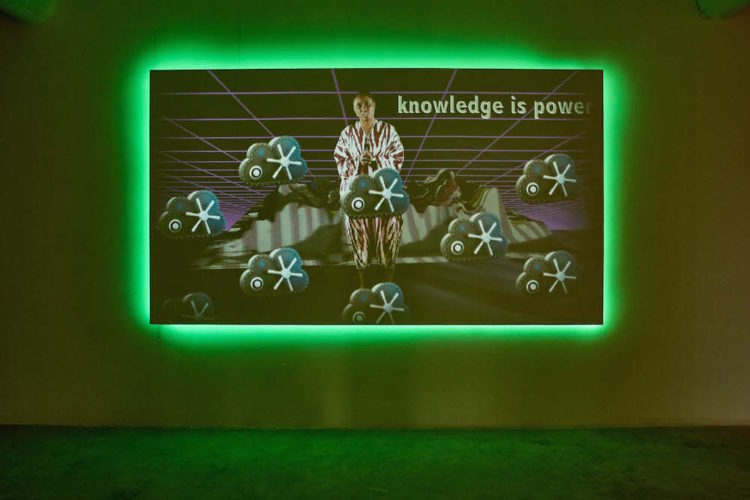

The idea of control is central to Rezaire’s show. In the curatorial description, she is quoted: ‘The Internet is exploitative, exclusionary, classist, patriarchal, racist, homophobic, transphobic, fatphobic, coercive and manipulative.’

Today’s empires are the media giants.

The internet is neither abstract, nor neutral, but ‘very real,’ says Rezaire. ‘It has real ecological, political and spiritual consequences on our beings […] It perpetuates certain histories. Histories of exploitation on the backs of Black and Brown people for the benefit of whiteness and white capital.’

Her video installation Deep Down Tidal plays with the idea that fibre optic cables are laid out under the sea following colonial shipping routes. ‘It’s not surprising,’ she tells me, ‘that the internet hurts so much because its architecture is based on routes of violence.’

The similarities run deeper. Colonisation was sold as a civilising mission ‘but what they did was to inflict genocide on indigenous people, to occupy land and to terrorise for the benefit and the increase of wealth of their own empires.’

Today’s empires are the media giants: Facebook has replaced the East India Company. Marketed as ‘helping people to connect to each other,’ says Rezaire, the internet has become another exercise in ‘exploiting our free labour. They’re stealing our data.’

Connectivity hasn’t even been a by-product: ‘We’re all suffering from disconnection. It’s just ironic that we’re supposed to be in an age of ultra connection. That’s a lie. Because we’re so closed off, to each other, to ourselves, to nature, to the universe, that we have to offshore our potential for communication.’ Her thoughts rush out, then she lapses into silence.

Alongside modern communication, the show explores ancient portals: plants, the womb and water. ‘Those portals have been shut down in most of us. It’s an attempt at opening up those channels, to align us to receive and download information and share this information among us, outside the channels that oppress and subjugate.’

One artwork has her aunt singing to water divinities in Creole. A self-portrait where she swings on a pole, topless, above flames, is part of an exploration into the ‘different archetypes of the black femme body […] They feel crucial in the development of my identity. They are narratives that have been forced on me to embrace or reject. This series is how I position myself within them.’

The sexual is key: ‘The political sphere that we inhabit has denied and continues to deny the value of the erotic, especially for womxn. And even more so for womxn of colour. They are trying to strip us away from our potential of self-realisation, which comes only when you tap into your erotic power. So that’s political.’

They do this ‘by surrounding it with shame, by devaluing and demonising it. Also when you tap into this power, when you respect yourself and your desires, and unlearn what the system has fed you with, then they’re going to punish you and that’s scary. So fear is what comes between us and the best version of ourselves.’

The world out there is racist, homophobic, imperialist and colonial but are you going to stop living?

She asks me to send her the interview before we publish, and I do – even though I know it’s not professional – because I like her. I’m not here to take her down, more to describe a new type of artist taking shape: modern feminist, part crusader, part lifestyle guru – she bottles water deemed sacred from the Nile to give to her friends. She returns the piece to me, edited slightly. She’s changed when she says ‘women’ to ‘womxn’ – an attempt, which has been in vogue for a couple of years, to reclaim the word from the patriarchy. How do you even pronounce that?

When I ask her which women (or should that be womxn?) she admires, she replies by leaving the room to fetch a pile of books. She holds up Sacred Woman by Queen Afua. ‘She’s a womb healer and she helped me overcome my angry vagina.’ How do you know if I have an angry vagina? I ask. ‘You do. We all do.’ She clarifies: ‘Just living your life through patriarchy and racist misogyny, that affects your womb and just shuts it down.’

Why not stop using the internet? I ask her, if it causes so much angst. Her answer is realistic: ‘Of course, I use it because the life I have demands that I use it […] But then I am trying to do this responsibly, but maybe that’s not the word because I am complicit. But I am just trying to be critical of the space that I inhabit.

‘The world out there is racist, homophobic, imperialist and colonial but are you going to stop living? It’s the space I’m in and a space that is fucked up. But I benefit from it.’

I ask her what would have happened if she had not started thinking about all of these things so deeply. The woman in her late twenties replies: ‘I’d just be sad. I mean I’m still sad, but I’m sad and powerful.’