I’m walking across the main street of Tunis with the South African director Sibs Shongwe-La Mer. The 23-year-old has just been awarded a prize for his film Necktie Youth in the debut film category at the Carthage Film Festival. It also won him Best South African Film and Best Director awards at the Durban International Film Festival.

Necktie Youth is a stylish dissection of the dissipation and disaffection ravaging privileged young people in the affluent suburbs of Joburg. It follows two friends Jabz and September (played by Sibs himself) who meander through their social circles in Sandton after a friend’s suicide. She live-streamed her hanging. They hang out, have sex, talk about sex, take drugs, talk about drugs, talk, have sex and then take drugs again. High on prescription medication, they blithely cruise in their parents’ expensive cars, past beggars at traffic lights, gliding through the everyday poverty of Johannesburg.

It feels like a revolutionary film; a political awakening that shows another side of Africa, far from the slums, the child soldiers and acacia trees; an Africa which is tapped into the same social network as the kids in a Larry Clark movie or in a Bret Easton Ellis novel. And so it’s perhaps inevitable that the young director is often asked to act as a spokesman for issues facing young people today. I’m ready to ask him about his politics, his film and his views on the future of a South African youth raised on Justin Bieber and Instagram.

But just as we meet, we’re accosted by a roving film crew who start firing questions at him in French. Although I’ve only just met him, I have to act as a stand-in translator. It’s all very intense. Especially when they thrust the microphone in his face and ask him – via me – ‘What do you think about terrorism?’

It’s only a couple of days after 12 members of the Presidential Guard were murdered by a suicide bomber in one of the main streets of Tunis.

‘I think it’s terrible and people shouldn’t,’ Sibs replies. It’s perhaps the only thing you can say.

So the first question I ask is how he now deals with being treated as an authority on most things.

A lot of people expect me to be a representative and a spokesperson. I get this question quite a lot: ‘Do you think your movie represents the whole of African youth right now?’ No, I don’t.

There are a lot of kids who are OK and have good lives. I can only talk about a certain demographic that I experienced personally and a corner of the world I grew up in. I can speak for about ten people who are all my characters.

Are you trying to say something about the state of South Africa or are you trying to say something about the state of privilege?

It’s not even about South Africa. A lot of African cinema is about an impoverished kid from an Ethiopian ghetto… but just because you’re not from there doesn’t mean you don’t have your own struggle. I wanted to level the playing field by going, yes, these kids are privileged, but they’re over-privileged. It’s not a fight for food or trying to eat every day but it’s an existential conundrum. Which a lot of my friends went through…

Or they are going through?

Well, no not really. I have a different group of friends now.

What?! You’ve got rid of all the druggies?

No, no, not at all. I mean, everyone’s a druggie. Every fan is like, ‘Sibs I love your shit’ and then ‘Do you want to go smoke some weed?’ and I’m like… Jesus. It’s stupid. ‘We want to party with you!’ No! I want to go home to my hotel room and sleep.

I’m trying to make other films and tell other stories but people come out of Necktie Youth and all they want to do is party with you or party with September. I‘m like: No. I’m here doing a job and I’m grateful that you came but after this I want to go and sleep or write my next movie. I have meetings and stuff. I’m not just like ‘Wooo! Rock n roll’ but everyone has that assumption.

It’s funny because when you see that film you don’t get the impression you enjoy drugs. At no point do drugs look fun.

It’s escapism. It’s kids who have nothing else to do with their lives. Jabz and September are not characters that I’m like ‘Oh my God, I wish I was friends with you.’ They’re very self-obsessed. They’re two friends sitting in the same car but September is so obsessed about his own stuff that he’s rambling without realising his best friend is falling apart at the seams. There’s a lot of comment in the film about social media and the ‘I’ generation.

I was wondering why you shot it in black and white. Does is have anything to do with Instagram and creating a barrier between the viewer and reality?

It’s not Instagram but it was a divorce from contemporary cinema in a big way. It’s an homage to the films I grew up with. When you’re in Joburg and you’re watching Breathless and you see Paris for the first time and it’s shot in black and white. There’s this mysticism and hyper romance. So if I’m going to take you to a world you might not have seen, I’m going to take it back to genesis and make it appear like a lost African document.

Our cinema is emerging only slowly over time.

That language of black and white was before Africa had a voice in cinema. It’s almost like I’m showing a new world but in archive of the start of African film. The beginning of a real conversation. I want to divorce it from this idea that I’m shooting a film about ‘youth’ so it has to be pop colours and really HD. No, I want to shoot these kids’ stories almost like an homage to Fellini, but also to Godard and skate board films. I wanted to dance with the film and make it feel fresh. To take on contemporary subject matters but looking like it’s from a different time… Looking like it has maturity but it’s about immature subjects.

Ok jumping around a bit… let’s talk about terrorism, again… No, let’s not… most of the relationships in the film are between black men and white women. Is that what guys from Sandton do?

When you make a South African film, people always like to put the emotional focus on the separation of apartheid and the categories of black and white or gay and straight. But these kids are united in this issue.

There a fascination that’s happening with race… not a separatism.

Because of the internet, they all grew up with MTV and probably watched Little Wayne on TV. That black experience is fascinating to them…

Yes, they say ‘nigga’ the whole time, which is so American…

We didn’t try to not sound South African but I did tell them to sound a little American because there’s an Americanising of young people. But we’re not American. We’re Zulu kids from Sandton. But the internet has brought about a collective identity that’s spreading through pop culture.

And does it work? Do they recognise themselves in it?

Actually that’s the one thing that I think is good about social media and MTV and stuff like that. In Sandton, boys grow up watching Miley Cyrus. There a fascination that’s happening with race… not a separatism. My generation in particular is very interested in each other. These kids grew up in households where their parents didn’t talk to other black people. And the black parents… well, those are my parents. It was shot in my house. My dad was going to act but he’s a terrible actor.

When we made the film, my career as a filmmaker was non-existent so my parents were like, ‘Why are you even making this movie?’

But now you’re a big star are your parents clamouring to be in your film?

My dad now says when I’m at home, ‘You need to just buckle down and really focus right now because you have so much opportunity… why are you sleeping? I thought you came here to write!’

Please tell me your parents have a portrait of Gandhi in their bedroom like in the film…

No, no. That’s my bedroom! Because they wouldn’t let me shoot in their bedroom.

So you have a portrait of Gandhi in your bedroom?!

Yes, yes, I know. That’s also how these families are. They’re trying to be like pseudo-monarchy. You get a bedroom and your parents put the art up. You can’t put a poster up… every room has to pristine. That’s why everything was shot very still when you’re in the house. When the friends talk in the park, it’s roving cameras. It is loose, free and exciting.

Normally, they’re not in charge of their life and that’s what gives them their malaise. What do you long for or how do you progress when you know that you probably don’t have to get a job ever? They don’t develop passions; they become very lost.

What have been the reactions of your friends?

Well, I cast all of my friends in the movie. Jabz is Bonko Cosmo Khoza who’s one of my great friends.

It’s weird because as you’re watching Necktie Youth, you know it’s all going to go wrong though you might hope otherwise. But at one moment, Jabz looks up and you look at his eyes and you’re just like, you’re f*cked, mate.

A lot of the film was based on truth. I told him ‘Dude I want to cast you in my movie’. He’d acted in university and dropped out. We did a short version of the film that was 40 minutes long that we shot on a thousand dollars called Territorial Pissings. It went to the Venice Film Festival and allowed me to make this movie.

I told my producers straight up; he’s going to be Jabz but he got fired like 11 times before we even started rehearsal. He would never show up! Or would come seven hours late.

Was he taking drugs?

Yeah! Or he just disappeared. He dropped off the grid. And my producers said ‘We’d don’t have enough money to carry on shooting if he just disappears for four days. The whole thing is f*cked.’ So we did other castings but it didn’t feel right to me. I wrote that story with him in mind because the whole story is autobiographical. It’s based on the suicide of my girlfriend when I was 14. And it’s pretty much how I thought I would end up. He was the only person who could understand the loss and understand being mixed up.

So then I told the producers I’m not going to make the movie without him. And for the last-chance screen test, he came four hours late. And when he showed up I said I had meetings and he would have to wait. He waited in his car till 8pm that night.

So what changed?

That was the moment. I got out and he was sitting in his car in the northern suburbs of Joburg. So I said let’s take a walk. And he said ‘Dude, if something meaningful doesn’t happen to me soon; I’m f*cked and I’m going to jump off a building’. And so we were talking and smoking like September and Jabz in real life. So I asked him ‘Why can’t we just do this … in front of a camera.’

I told him that he’d have to show up every single morning at 6am when everybody else got there and the producers might let him do a camera test. And so every single day he showed up and waited from the beginning of the day to the end of the day on the couch. Eventually the producer said ‘OK, let’s give him five minutes’. So we acted out in the office the ending scene of the film when we talk about how much we hate Johannesburg and how Johannesburg is trying to kill us. He has such an honesty as a performer and it’s not because he identifies; it’s because he’s an amazing actor. I write roles for him. The producers said – it has to be him.

From then on it was 300 per cent dedication from him. He came to rehearsals and we wouldn’t even read the script we would just talk about the psychology of the characters.

Was there a script? Sometimes feels like there is one but then the characters are in the park, talking about Chat Roulette – is Chat Roulette still a thing? – and it sounds really unscripted.

The guy that plays that role is not an actor. But a lot of the time we would start the scene and I said, ‘As long as you hit this beat, I don’t care how you do it’. In the park scene it’s only the two guys who play the drug dealers who had actual lines. They were the only real actors so they knew where the scene had to go. And I placed them with people they hadn’t even met…

And you knew they were going to say something stupid and high…

Stu is a guitarist for a band called the Stellars that I used to shoot music videos for and we’ve been friends since back in the day. That Chat Roulette is a true story from tour. This guy is watching his girlfriend on camera, so I sit on the bed – as I’m quite interested – but out of frame and then the guy starts masturbating and then all his friends jump out – Euuughh. How traumatic and juvenile is that? We were those kids!

Necktie Youth is a film about how they have nothing to do but get high all the time.

So as soon as he arrived on set, I told him ‘Dude, tell the Chat Roulette story and then we’re going to go back and tie it in to Emily’s live stream.’

You have to direct more than you give instructions. You can’t write every single thing. You have to get in the same space and the same mentality. And then that‘s when Andile says ‘Did she hashtag her death?’

And it has to be like that because the movie is about the fact that nothing happens so I have to give back control to the characters. Necktie Youth is a film about how they have nothing to do but get high all the time.

Matty – the guy in a wedding dress – is a really good friend of mine and when we got on set, there was water in the beer bottles. After we did one take, all the actors came to me and said ‘Dude, listen here. This isn’t working…’ So I sent out for some six packs. My cinematographer and I – whom I’m like best friends with – we were always in control but there were some scenes… Like that party scene when Tanya gets wasted.

Is the place where they have a party a real place?

It’s called the Zebra Inn and it’s like a taxidermy slash brothel slash place where old men have a drink. But I thought I’m not going to be able to put out a casting. I don’t have many friends… I have like four friends… And get people to come to this bizarre weird place if we don’t have a party and pay them. But everyone got annoyed because when they were getting drunk, we had to say ‘Cut music! Everyone quiet! But keep dancing!’ So 200 kids were like ‘Err cool. I’ve got my cash and I’m drunk so I’m leaving.’ And then we did the intimate scenes with Tanya and Kamogelo Moloi after.

Kamogelo Moloi, he’s great.

Well, he was actually going to be Jabz after Jabz got fired like 5,000 times. He’s an incredible performer but particularly as he’s a gay actor playing a heterosexual role. He was first written as being quite smooth talking, you know. But actually he’s a very affectionate human being. I don’t discuss race with their relationship. They’re just two people who love each other. That’s the South Africa I love.

‘Sometimes the kids are f*cked up. There’s just nothing you can do for them.’

He’s certainly not September…

September is two things: he’s obnoxious and he’s comic relief. I wanted to show the balance. There’s a lot of funny things that happen in tough times. September is a joke. The producers told me I had to play him. It’s difficult to act, direct and control everything when you’re shooting so quickly. I couldn’t even review September’s takes. I didn’t even remember all of September’s lines so I thought I’m just going to go off the cuff and if Bonko laughs or my cinematographer laughs then it’s golden.

And September doesn’t change at the end.

No, I didn’t want a resolution. If I knew the answer to why my friends feel like this and why generations in different societies feel like that – from Columbine to wherever – if I knew that, I wouldn’t be making a movie I would be trying to fight it. I don’t have the answer. That’s why I wanted to end it with the line: ‘Sometimes the kids are f*cked up. There’s just nothing you can do for them.’

So that’s why at the end you see the legs, the hall, the parents and the haunting sound of the suburbs.

I just wanted to be like: done. We lost another one.

We have so many preconceptions of the internet f*cking up young people. Is that what happened?

The internet is good for globalising subcultures. You play the film to kids in NY and they walk out saying ‘Yeah, dude, that totally feels like the life I live.’

Americans get het up about cultural appropriation. It’s nice to see another take on it.

Yes, it’s good to see a unified global generation. You can speak to someone in France and make a joke about Justin Bieber. They’ve seen that meme too. But it’s also so separatist. It’s all about putting your best foot forward and saying ‘Follow me, follow me.’ September is the internet: he’s the kid who’s so rap he doesn’t have any substance. It’s probably me in real life. I’m always telling stories… ‘And this one time dude…’

These kids are unable to be human to each other. They all break apart separately in the same space but they’re still trying to get approval. It is a very Instagram and Twitter generation mentality. ‘Oh, I want to be liked’. But no, sometimes when you’re broken you should actually be broken and then you’ll see who are your real friends.

When Fees Must Fall happened did you feel that you should have talked about it in your film?

When it happened a lot of people said ‘Sibs, why have you fallen off the internet? Why are you not commenting? Why are you not talking?’ But I didn’t even finish high school. I didn’t go to film school or anything. I can’t be the spokesman for that.

How come you didn’t go to university?

I dropped out of high school before my last two exams to go work in a production company. And my friends said ‘Dude you are so f*cked. You are the most unemployable human being.’ And I’d just go to production companies asking for an internship and they’d say no because the people who make coffee here have finished film school. So people were not interested in my art or me being part of their structure. So that’s why I had to make art on my own. It was out of necessity. I had to finance my own stuff in the beginning and live in the inner city in a small box and shoot bands and stuff.

So you parents didn’t pay for it?

No. My parents are very much like, if you make a commitment you’ve chosen this way to go with your life and we’ll help you in certain small ways but otherwise you’re never going to learn any drive and know the value of things.

The parents aren’t very present in the film.

I went through what Jabz went through and probably had it worse. My father went to the Berlin premiere and when he walked out of it, he turned to me with a troubled gaze. You could see it really hit home and what he had to go through with me – this lost kid – and he said ‘It’s not nice. I don’t like that feeling but I feel that your film is necessary.’ It was traumatising because I filmed the hanging in my parents’ house because I wanted to tell my story. So he had to see himself watch me…

And presumably they knew your girlfriend.

I had many suicide attempts and was trying to escape and do as many drugs as I could. I was very lost and always in trouble, I was always getting arrested. So my parents really, really struggled. My dad always used to say ‘For all this, for all the stuff I’ve worked hard for I would give anything to just know how to make you right.’ So that’s how the story would have ended.

Being twelve, as a skateboarder kid and watching Larry Clark in my room was like a Molotov cocktail going off.

And it would have happened if I didn’t have my art. My friends ended up killing themselves because they had nothing. But I was always in my bedroom, making art, making music. I had something to drive to. I started the first draft of this film when I was 14, five days after her death. And I’ve been working on this film for the past nine years, right until we shot it.

How do you feel now it’s over?

It’s disorientating. Life does move on but it’s also very hard to be going around constantly talking about something that’s very traumatic. It takes its psychological toll. I get to points when I can’t do press.

And how psychologically traumatic is being constantly compared to Larry Clark?

It gets compared to Kids as a general rule but I like the Larry Clark thing because I loved Kids. It was one of the first films that made me want to be a filmmaker.

Being twelve, thirteen, as a skateboarder kid and watching Larry Clark in my room was like a Molotov cocktail going off.

It was so liberating. It was one of the first times I realised, ‘Hey I want to do this. This is the profession I want to do.’ Especially in South Africa where we don’t have a very big cinema culture so most of the films I saw were like Oceans Eleven. It was the first time I really identified and I felt the strength of cinema hit me against my chest. So why would I shun from comparison if it’s something that has inspired me? How can that not be an honour? Because Kids is the youth culture film. But it’s totally different because it is a different energy; Kids has a decadent passion of youth. This film is very much about a lostness.

It also reminded me of the spirit of film adaptations of Bret Easton Ellis – that void and nihilism.

I am a nihilist so I make nihilistic films in general. I haven’t made one short where someone doesn’t commit suicide yet.

So what’s next? A Disney film?

So this is the funny thing… being in the Hollywood machine. I’m doing this film called the Sound of Animals Fighting which I’m writing now and we’re shooting next year in Sao Paolo, Brazil, and it’s about kids, hedonism, falling in love… and they get involved in the drug trade. Before I came out with a political film called Colours of the Skull that everyone said ‘Woah, Sibs, it’s very dark’.

What… Is it about terrorism?

No! We don’t have much of that in … apart from the terrorism we inflict on ourselves. The film tracks the last days when Mandela was about to die…

There’s so much stuff we don’t talk about which is ruining the spirit of what Nelson Mandela fought for

Is Mandela still relevant?

He is but he’s not. And it saddens me. Because I am a patriot and I think Necktie Youth is a very patriotic film. I have been approached by people who say ‘You have no right to depict your country in such a negative light’. And I say, ‘No, it’s because I care. If I didn’t care I would have been making a rom-com’. We have to talk about it.

African cinema is often praised for telling the ‘African’ side of the story but does that mean you feel pressure to portray the continent in a positive light?

We’re not ready for that. Not in South Africa. We have so much pain and so many issues that we need to confront that or things that are swept under the rug and avoided. Especially in Sandton. Most people experience their kids to be the same but everyone puts on this façade of being wealthy and having children that are alright. But behind that, there’s so much stuff we don’t talk about which is ruining the spirit of what Nelson Mandela fought for. When we were growing up we saw posters of black, white, Asian kids of my generation who were going to be the first free generation and we were going to fix the country. And there was such an energy of unity. But Necktie is post this.

There is all this pressure on the youth to remedy South Africa but I also wanted to show that the kids are like ‘I just want to go to America.’ I hate this place where there’s a general sense of nihilism instead of a fight.

Do you think there’s a political solution?

I think there needs to be an emotional solution before a political one. That’s what Mandela was; he didn’t just fight for the country; he had such a soul to him; he overwhelmed not just South Africa but the world. He wasn’t a president; he was a spiritual figure. Now a politician just wants to be an entertainer; it’s satire. But that’s why the father in the film says that there’s only going to be one Mandela.

If we don’t start concentrating on each other, if we don’t find a way to communicate, if parents can’t speak to their kids, if kids can’t speak as honest human beings about how we feel, and find a sense of humanity and love in the world, we are condemning ourselves to a world that is not good enough.

But the only thing I can do is make movies. I am not going to be Mandela but maybe my friend will pick up a guitar and say something. That’s all we have.

Our hour is over and it feels like we have been talking for ages. We pay the bill, ignore the little girl who’s begging at our table, and walk back towards the five-star hotel we’re both staying at.

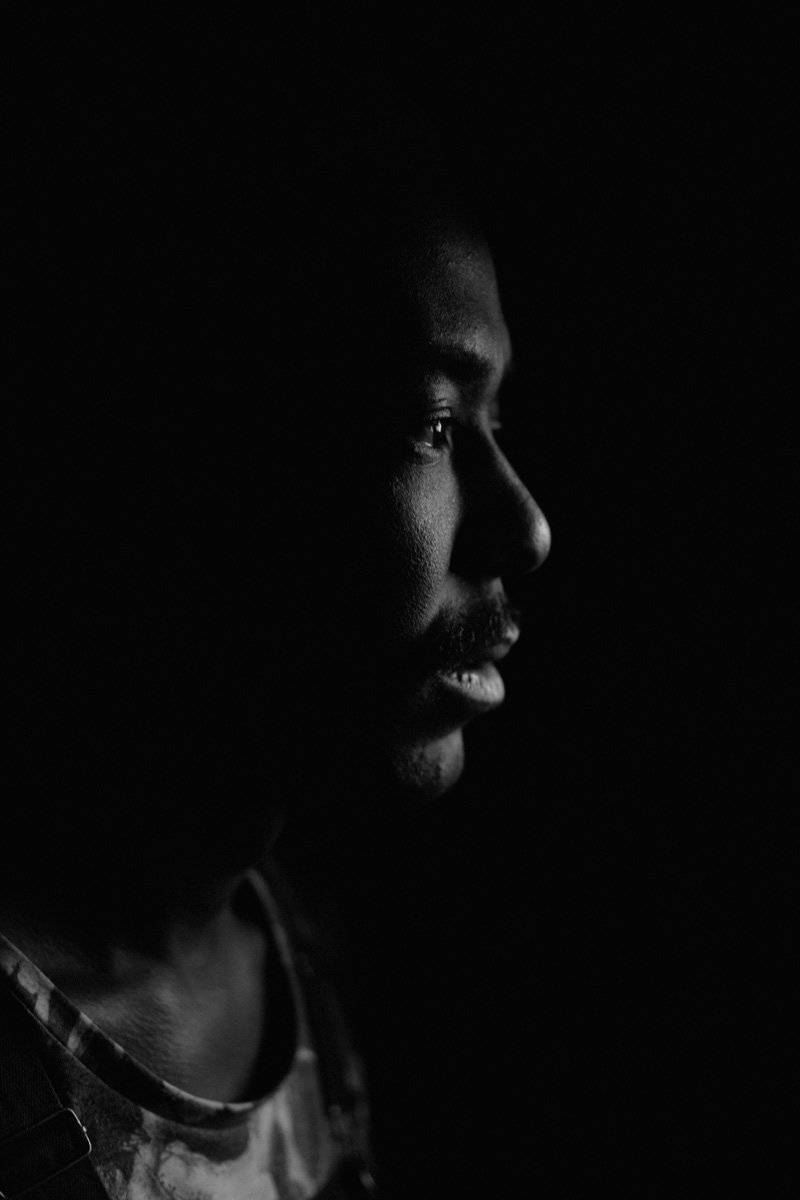

Portraits of Sibs Shongwe-La Mer by Chuanne Blofield.