For those of us who were close to Peter Beard, the 19 days between his disappearance in the afternoon of March 31st and the discovery of his body on April 19th in Camp Hero State Park near his house in Montauk, Long Island, were harrowing. As days passed and police searches proved fruitless, we came to gradually accept that our beloved friend, the larger than life photographer might have made another legendary exit.

In the end, this exit was final, and several of the send-offs published over the last three days led with this beautiful statement that his family shared on social media. “We are all heartbroken by the confirmation of our beloved Peter’s death. We want to express our deep gratitude to the East Hampton police and all who aided them in their search, and also to thank the many friends of Peter and our family who have sent messages of love and support during these dark days.”

I met Peter Beard on a visit to New York’s SoHo neighborhood in January 1998. I came to find out it was a few days before his 60th birthday. It was the coldest winter month, and I remember that he was walking around in sandals when I stopped him and introduced myself. Even though I was then living in London, I had been following his art (and the stories about his hard-partying ways) since I was a teenager growing up in Paris. I had just seen his latest retrospective at the Centre National de la Photographie, in Paris. Our first conversation was about his numerous travels to Africa, his Nairobi “discovery” of the supermodel Iman, whom I’d met and interviewed for the first time two months earlier in London, and the moments of revelry he’d enjoyed in Paris as a younger man.

In those days, I was starting to write more about “transculturalism”—and shared cultural affinities—for my new, London-based monthly magazine, TRACE, and I wanted to understand the thinking and lifestyles of adventure-seekers and fearless creators who found themselves at home anywhere in the world and felt compelled to document their interactions with strangers. Environmental activism was not yet popular, but as a West African from Togo, I was drawn to Peter’s tales about life in the wild, mostly in Eastern Africa, and the damage humans have been doing to animals and their natural habitat.

Four months after our chance encounter on Wooster Street in SoHo, I decided to move from London to New York City with a small team of writers who were down for whatever American dream I’d sold them on. At that time, I was funding the magazine on a shoestring budget, and my team and I were living from hand to mouth. My idea was that TRACE would eventually find a bigger audience in America, given its transcultural approach to reporting about hip hop and youth culture, so we launched a US edition in the spring of 1998.

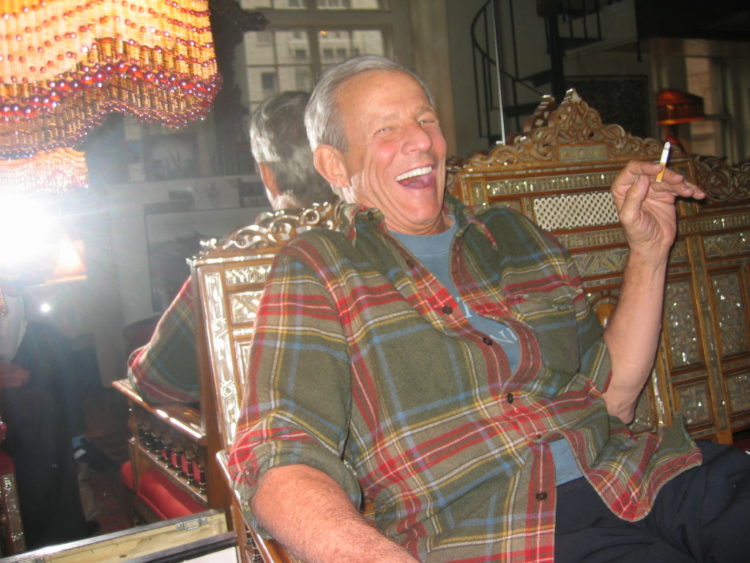

Little did I know that the office space I’d find, through personal connections, would be located at 476 Broome Street, right around the corner from where I’d first met Peter. Actually, our TRACE Magazine office, a small second-floor loft turned editorial war room, ended up being just a floor above the ground floor art gallery where Peter Beard worked and sold most of his artworks. The gallery was called The Time is Always Now, and that name aptly described the fun (and countless late night discussions) so many of us had there, drinking with Peter and the many visitors, associates and collectors who came in from all over the world.

On some lunch breaks, I would race down two flights of stairs to the gallery’s basement, where Peter Beard would be drawing curved lines and seamless, asymmetric patterns on artworks with different kinds of ink, including ink made from his own blood, or from animal blood he’d collected from the butcher’s. Diaries and newspaper clippings would be covered by sepia-toned photographs, found objects and dried insects. I was in my mid-twenties then, and every time I recognized an interesting quote, or a famous face I was intrigued by, or even a particular elephant I found to be particularly majestic, Peter would indulge in reminiscence by telling me how and where he’d met the beast behind the gesture, or the person behind the thought.

Some people just come into your life, and you know from the start that they will play a big role in your awakening. Pretty soon, our friendship evolved to mentorship, and we started working together. Peter told me that as a media entrepreneur I should always value my independence and trust my instincts when meeting new people, and that I should never choose the most obvious image when editing a series of photographs. He knew that we were struggling financially, and despite that he encouraged me to take creative risks.

He felt that we shouldn’t try to dilute the essence of the magazine by making it more commercial, in an attempt to please new readers or advertisers, but that rather, we should endeavor to be even more radical in our assessment of injustice, racism and sexism in America and in other societies. In essence, Peter Beard encouraged me to just be me.

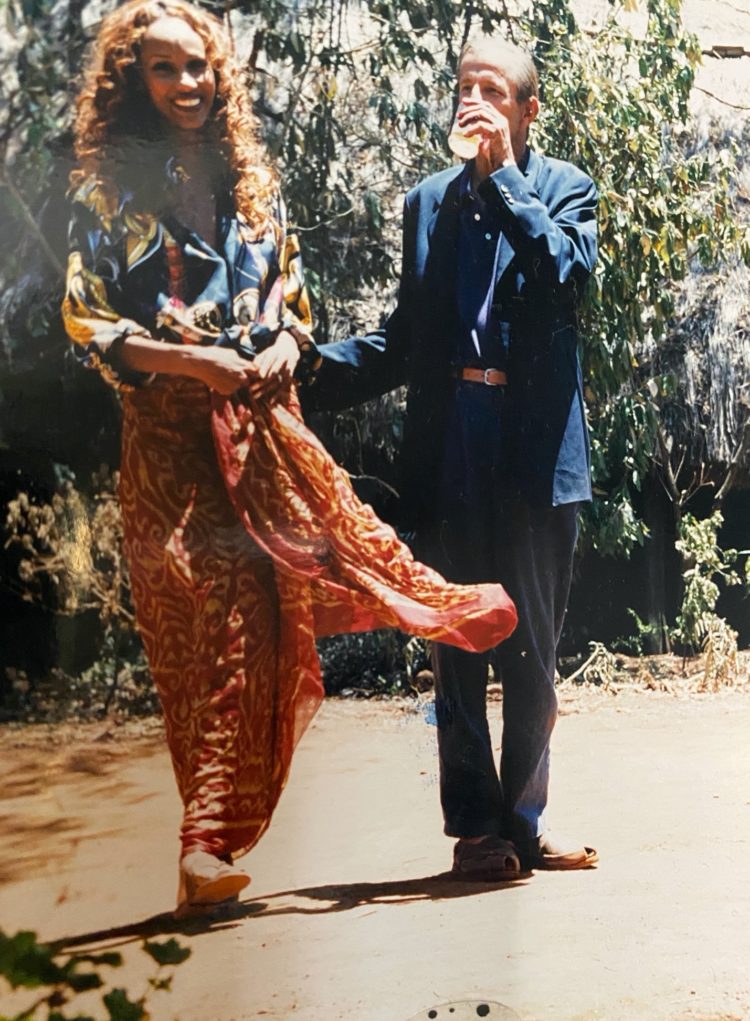

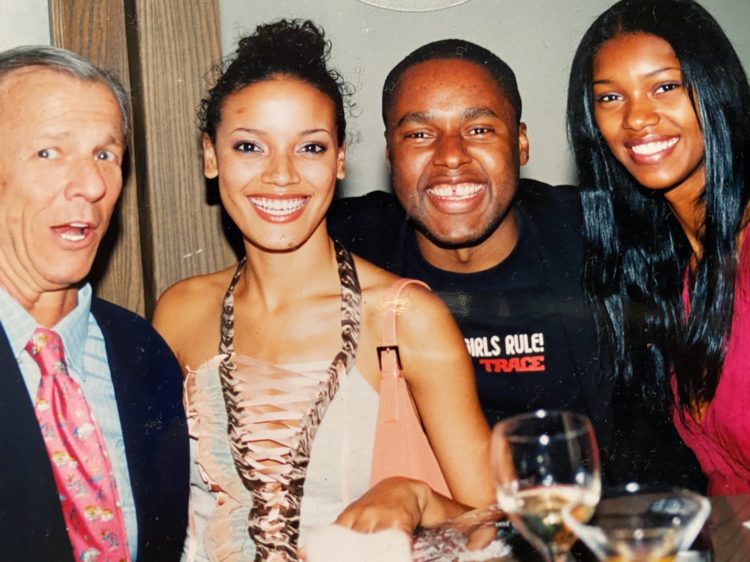

As a native New Yorker, he explained how my African values would trigger my defense mechanisms in New York’s hard-nosed business environment. As a lover of female beauty, he particularly enjoyed our annual “Black Girls Rule!” issue. He photographed fashion spreads (and even a limited-edition oversize poster supplement) for TRACE Magazine.

Together, we hosted several magazine launch parties at The Time is Always Now gallery. The party I will never forget is the one we threw on September 10th, 2001. It was the night before 9/11, and the theme of the function was “transformation.” Late on that night, one of our guests got (slightly) injured, because a speaker fell on his head. (We were not always very careful at the time, especially after we’d had a few drinks.) Peter said I should take the guest to the hospital immediately.

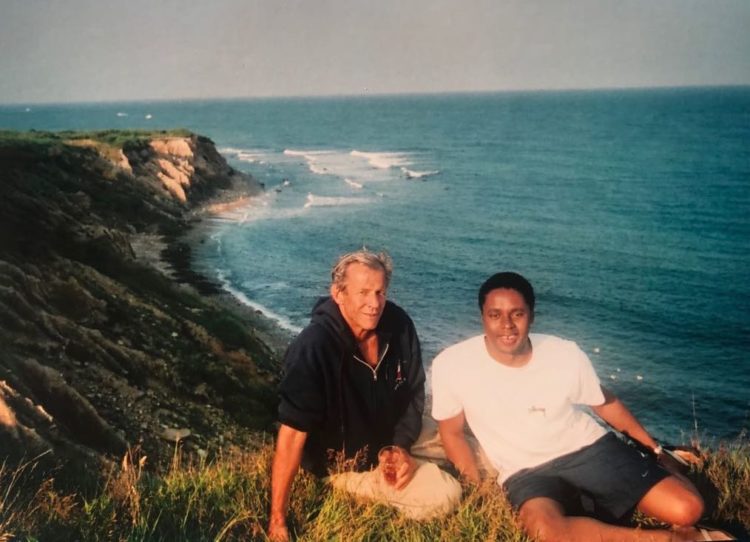

A few hours after leaving Saint Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan’s West Village, we all found ourselves dealing with the aftermath of the four coordinated al-Qaeda terrorist attacks. In the months that followed 9/11, different New Yorkers attempted to overcome their grief in different ways. Because I was (and still am) living near Ground Zero, Peter’s beachfront home in Montauk became a refuge for me. It was a place I would escape to on some weekends, when I got tired of decoding the conspiracy theories that came out of our neighborhood, which was full of anxiety and paranoia.

I remember the writer Don DeLillo calling the September 11th attacks “the defining event of our time” and I find it eerie that I am writing this tribute to Peter during the coronavirus pandemic, just after Peter exited this world at another defining moment in our lives. At Peter’s estate in Montauk, I got to know Peter as a family man, the doting father to his young daughter, Zara, and I was finally able to understand the roots of his gregariousness after I finished the first of many long conversations with his Kenyan Afghani wife, Nejma.

It was difficult to navigate Peter’s idiosyncrasies without having first worked out Nejma’s roadmap to his brain and spirit. Peter was known as the ultimate ladies’ man, but he also enjoyed the company of men who would challenge him, intellectually and emotionally. I took an immediate liking to Nejma, who helped me figure out that Peter’s mental models were all about free association, and that art was therapy for him. Nejma became a mentor of a different sort for me. She was one of the few women who were able to understand Peter’s intuitive leaps without refraining them. Somehow, when he was too far gone, she found a way to bring him back to earth.

In his interpretations and depictions of life in all its forms, the things that Peter cared deeply about—the beauty in nature, people and animals—were manifestations of a thought process where the unconscious always found a way to rearrange the established order. Of course, some people will jump to conclusions and conclude that those disorderly thoughts that could be found everywhere in his art were rather just altered realities that came with a life of drinking and doing drugs.

I remember Iman telling me about a decade ago that, in all the time she’d known Peter, starting in the mid-seventies, he and his friends were always fueled by alcohol and recreational drugs. For my part, I found that Peter loved nothing more than a good, free-flowing conversation, and I came to realize, on his seventieth birthday, which we celebrated with Nejma and a few friends at Le Bristol Hotel in Paris, that Peter had always been the life of every party, and that alcohol and drugs might have been the easiest form of escapism when so much was always expected of him at social gatherings.

On one of my visits to Nejma and Peter Beard’s West 57th Street apartment in Manhattan, in May 2005, I couldn’t take my eyes off a framed black and while photograph of a beautiful young Nejma walking a London street with Francis Bacon, my favorite artist, in what looked like a solemn procession. Over the years, I asked both Peter and Nejma about the circumstances surrounding that extraordinary photograph.

I knew that Peter, Nejma and Francis Bacon were friends right up until Bacon’s death in 1992. I had also read that Bacon had painted Peter several times, but in piecing together both Peter’s and Nejma’s recollections of the context in which that photo was taken, I found my answer in Michel Leiris’ 1987 book on Francis Bacon. In that monograph, the French anthropologist and writer (who was also a close friend of Bacon’s) wrote that Bacon’s “essential aim is not so much to produce a picture that will be an object worth looking at, as to use the canvas as a theatre of operations for the assertion of certain realities.”

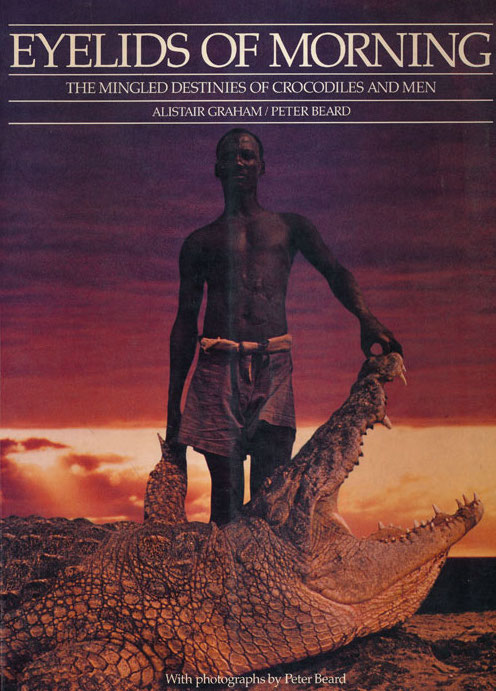

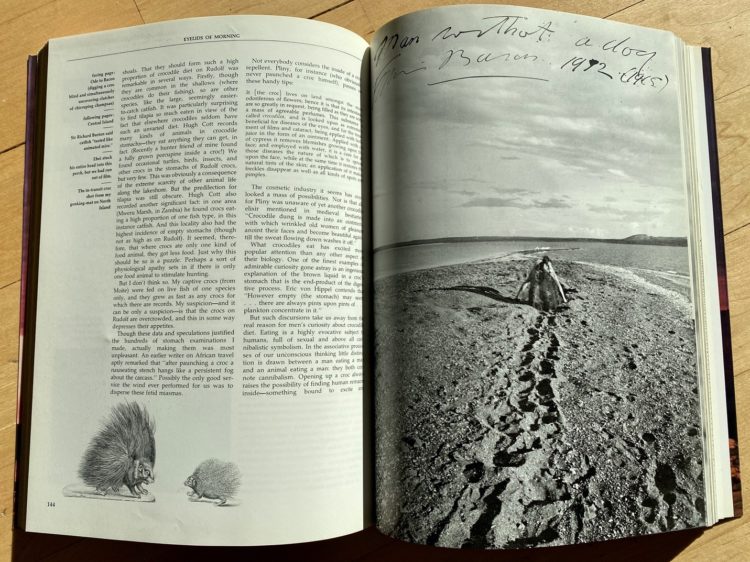

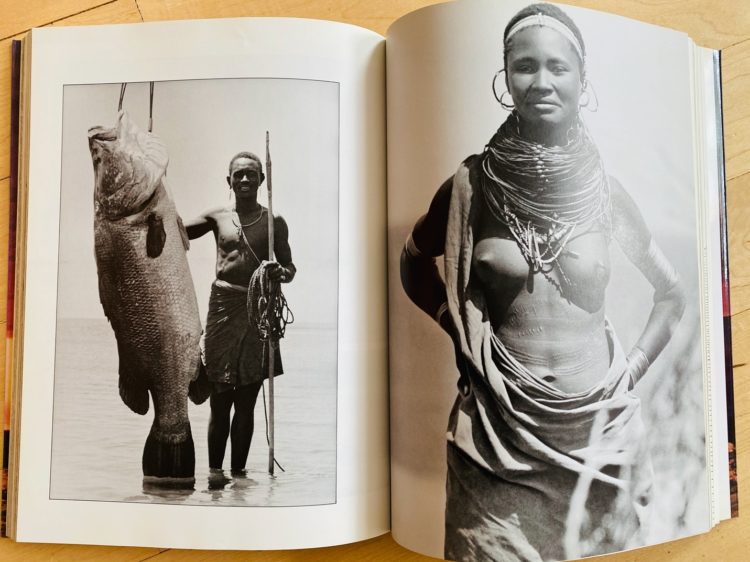

Leiris’s essay helped me understand that what Francis Bacon and Peter Beard had in common, perhaps a clue that explains their kinship, is an ability to spatially and temporally distance themselves from the subjects we see in their artworks. With that new understanding of their creative process, I was able to give a different reading to Eyelids of Morning, the 1974 book that Peter photographed and partly wrote with Alistair Graham, who had spent three years researching Kenya’s Lake Rudolph.

Most critics consider The End of the Game—originally published in 1963, when he was just 25—to be Peter Beard’s masterpiece, but I have a preference for Eyelids of Morning, which is about “the mingled destinies of crocodiles and men.” Eyelids is the kind of natural history reporting you just don’t see anywhere anymore, because that world and that wasteland are long lone. The book is “dedicated to all heroes, missionaries and martyrs, their perils, adventures and achievements.”

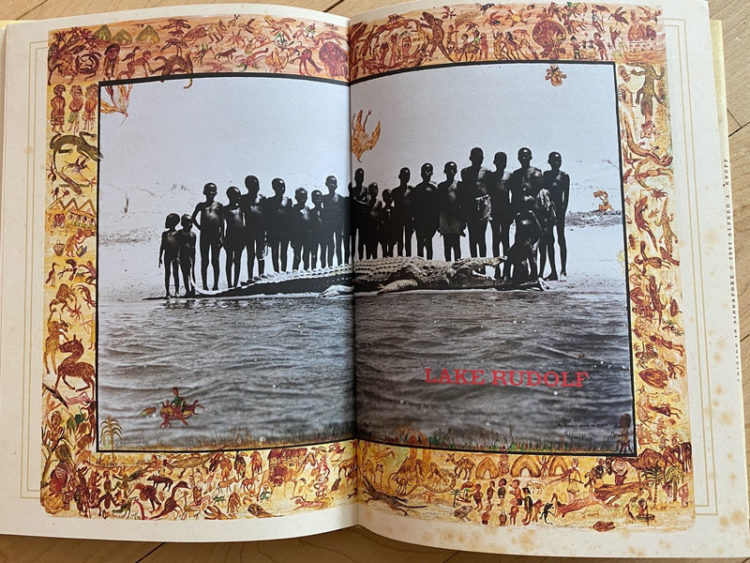

Peter Beard and Alistair Graham get so close to Turkana people in northwestern Kenya that it sometime feels as though the natives apportioned some of their mysticism and mythology to the two white men. Peter shares with readers an Ode to Bacon called “Man Without a Dog” on one of the pages, and even though the entire expedition feels like a moral hazard, I never get tired of the words and duotone photographs showing us how certain fishermen in Africa have engaged in dances of death with crocodiles for centuries. Those crocodiles, which have been ruthlessly hunted over the past 50 years, are not always protected as endangered species.

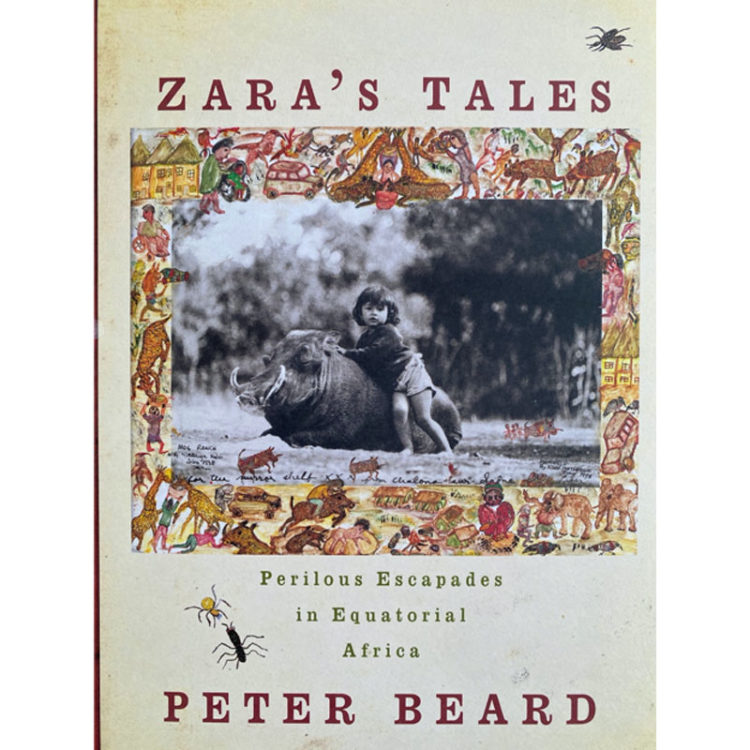

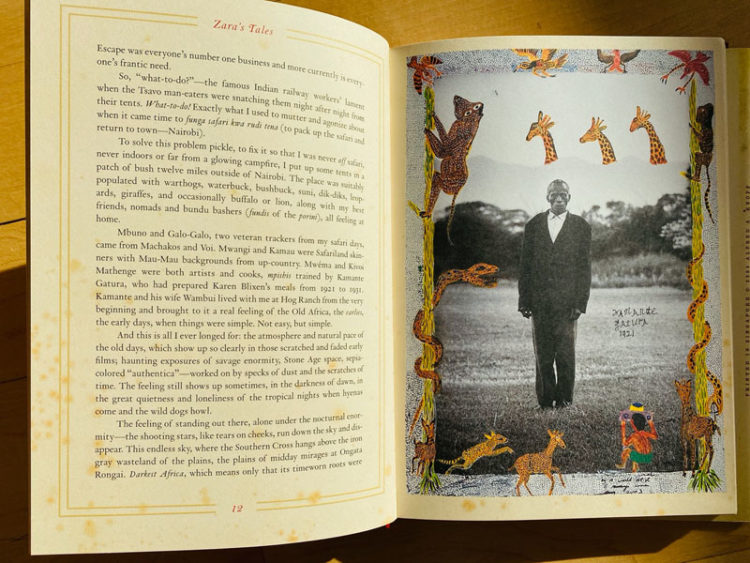

Among Peter’s later works, Zara’s Tales, published in 2004, stands out for its candor. More than a tribute to the people of Kenya, it now reads like a testament to the power of nature to bring harmony to our lives. Over the course of 11 tales, Peter shares with his daughter, now 32, some life lessons gathered from a life of wandering in and out of Hog Ranch, the spread he bought near Isak Dinesen’s former farm in Kenya. Zara’s Tales is full of stories about the endless sky, shooting stars, rough windswept waves, Lake Rudolf (now known as Lake Turkana), and the character of the people Peter chose to associate with in his time there.

One of those people is Kamante Gatura, immortalized in the book—and in other Peter Beard artworks—in a 1921 portrait where he is shown wearing a black suit and a white buttoned-down shirt, looking pensive in the middle of a deserted field. Kamante “had prepared Karen Blixen’s meals from 1921 to 1931,” Peter writes. “Kamante and his wife Wambui lived with me at Hog Ranch from the very beginning and brought to it a real feeling of the Old Africa, the earlies, the early days, when things were simple. Not easy, but simple.”

These last few years, Peter was ailing, having suffered a stroke and showing early signs of dementia. I ran into him and Nejma in August 2017, in Southampton, NY, at the birthday party of a mutual friend. The new moon supermoon had caused the solar eclipse to be visible from parts of North America that day, and Peter and I decided to leave the party guests and venture to the garden where we would see, though our paper glasses, how the sun had been blocked out and drowned the planet in Earth’s shadow.

Peter was in good spirits, and we talked mostly about his life in Montauk. He was no longer the life of the party, but he certainly had the demeanor of the curious adventurer he had always been. He was inquisitive, and he was still funny. He never lost his charm or charisma, but he was diminished. I never made it to his 80th birthday dinner that Nejma and Zara organized in January 2018, because I was out of town that weekend, but I am forever grateful for the blessing that had me cross Peter’s path in SoHo on that winter afternoon. In 2016, the writer Kevin Conley wrote that “Peter Beard might actually be the most interesting man in the world.” I believe there is some truth to that.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B_MNLVBAdcC/