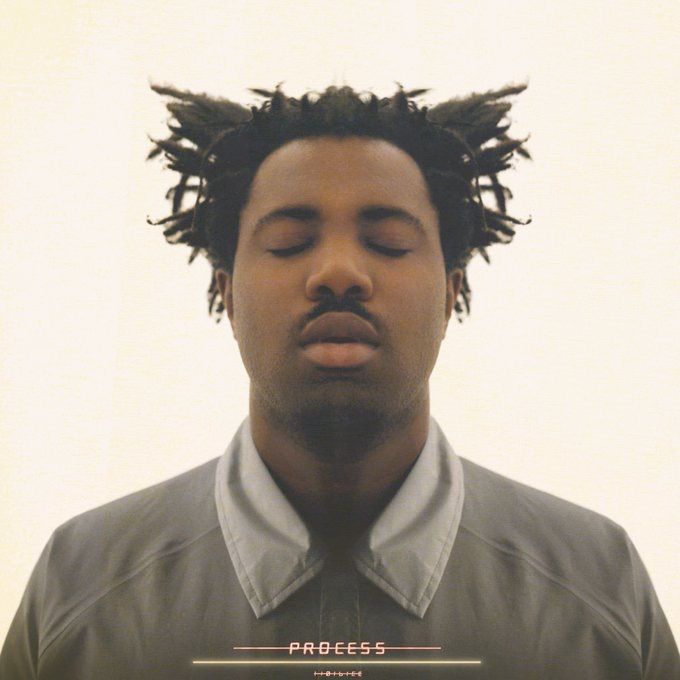

In February, British producer and singer-songwriter Sampha Sisay released his debut album, Process. It was a much-awaited solo release: the 28-year-old had already been singled out by Solange, Kanye West and Beyoncé.

These big-name collaborations started early in his career. Sampha had worked with the British electronic artist SBTRKT in 2010, had flown to Toronto to work with Drake, Ghana with Solange and LA for The Life of Pablo with Kanye.

His vocals reflect the pain and vulnerability behind this story of success.

On Process, his vocals reflect the pain and vulnerability behind this story of success. During these years, his mother had been diagnosed with cancer. After her death in 2015, Sampha left Morden, the area of South London where he grew up, this time to bury her in Sierra Leone.

Sampha released a 37-minute accompanying film, also called Process, a month after the album dropped. Award-winning American director Kahlil Joseph collaborated on the video. Over the past couple of years, Joseph has been the visual storyteller behind some of our favourite and critically acclaimed short films, like m.A.A.d for Kendrick Lamar and Lemonade for Beyoncé.

Process starts in Sierra Leone: an empty pool at Freetown’s national stadium. Also known as Siaka Stevens Stadium, named after the country’s first president, it is a multi-purpose complex that is also the country’s largest venue for live music performances. A troupe of dancers steadily awakens to the sounds of Plastic 100 °C, a single on the album, and traditional Sierra Leonean drumming.

Kahlil Joseph’s images flash between Freetown and Morden, taking us back and forth, tracing Sampha’s own journey from the birthplace of his parents to his own birth, from ancestral narratives spoken by his grandmother, Fudia Sisay, to images of growing up in London.

My film 'Process' with Kahlil Joseph is out now on @AppleMusic! https://t.co/ucFrEYvn1O pic.twitter.com/dUkdQBwNIv

— Sampha (@sampha) March 31, 2017

The film immerses the viewer into the mysteries that constantly surround us, without them unravelling. We travel through the infinite and eternal, and return to the smallness of our being, renewed and invigorated.

The sea symbolises loss and entrapment as Sampha is dragged down into its deep depths.

In one shot, a woman hangs in a spinning cocoon. The poem of British-Somali poet Warsan Shire, ‘Mother is a cocoon’, which accompanied Beyoncé’s underwater pregnancy shoot, surfaces in my mind.

Shots of the ocean recur. The sea symbolises loss and entrapment as Sampha is dragged down into its deep depths. It has the dual ability to free us as well as claim us. It symbolises rebirth, transformation, and release.

The film captures a moment when Sampha performs What Shouldn’t I Be? on his piano in front of the waters of Bureh Beach, one of Sierra Leone’s most popular beaches. With contrasting imagery of his childhood home in Morden, he sings sweet reassuring lyrics: ‘You can always, you can always come home.’

Other artists from the diaspora who have produced albums exploring the return to their Sierra Leonean heritage. The latest LP from New York City-based hip-hop artist Dev Hynes (that’s Blood Orange) was called Freetown Sound in honour of the city of his father’s birth. Irish-Sierra Leonean singer Sally Matu Garnett, who performs under the name Loah, blends jazz, R’n’B, and Krio (a derivative of Creole and the de facto language of Sierra Leone) into her music. Yet, despite these similarities, Sampha retains his own niche, reflective of the personal loss that makes his sound unique.

One song, (No One Knows Me) Like the Piano, opens with a melody Sampha plays on a piano, bought by his father when Sampha was aged three. His father played music from Sierra Leone and Mali in their Morden home. The sounds pop up throughout both album and film. Sampha’s father also died of cancer, a decade before his mother. In a raspy melody Sampha chants: ‘No one knows me like the piano, in my mother’s home.’

Towards the end of the film, along with the dedication to his mother (‘I’m connected with you, no matter where you are’), one of Sampha’s brothers can be heard explaining the significance of his last performance at the Globe Theatre in Freetown to an empty crowd: ‘Piano song, that was played at our mother’s funeral. That’s his last song. That’s the one that really hits home, because that’s the last, that’s the last song he sang for his mother.’

The film, a pairing of the two talents, brings back memories, sketches reflections, whispers names, outlines places, enhances joy and screams pain.

This is part of a guest editorship series by Nadia Sesay. She’s producing a special feature for TRUE Africa on Sierra Leone.