The TRUE AFRICA 100 is our list of innovators, opinion-formers, game-changers, pioneers, dreamers and mavericks who we feel are shaping the Africa of today.

Osvalde Lewat is a Cameroonian documentary maker and photographer, who began her career as a journalist. She was born in Garoua, Cameroon, but has lived in the DRC, on and off over a period of eight years. Her documentary The Forgotten Man (2004) focuses on a prisoner held captive for over 33 years despite being sentenced to only three. In Black Business (2006), Osvalde delves into the emotional plight of families whose loved ones have disappeared at the hands of the Cameroonian government in the 1990s; it was banned in Cameroon.

Her latest project, Couleur Nuit is a book and exhibition project documenting her journeys into the obscurity of the Congolese night, from Kinshasa to Lubumbashi. None of the pictures are retouched; the focus is on chance encounters with strangers, as well as the light one can find in the middle of the night.

Why this fascination with Kinshasa and the Congo?

The Congolese people are unique, they have so much energy, and a completely original perspective on life. They are so exuberant, as if it were a form of catharsis, because where you see joy you also see tension. I think a lot of that originality can be traced back to their colonial history, which was much tougher than in many other African countries.

In these Kinshasa neighbourhoods I saw a world that was full of life; it was a different kind of beauty and poetry.

I guess my fascination started with what I saw and experienced in la Gombe, the municipality in the Lukunga district of Kinshasa, which is home to businesses as well as expats and more affluent residents of the city. That municipality was originally reserved for white residents, and the métisse had their own quarters as well, separate from black people. Just a few decades ago, one needed a special pass to enter this municipality. That pass was only given to those who had passed a test called ‘évolué’ — meaning evolved, adopting a European lifestyle, eating with forks, and so on.

Having seen the limits of la Gombe, I wanted to discover other aspects of the city. So I asked a friend to take me to ‘the other’ Kinshasa. When I first went into the night in Kinshasa, I started photographing all kinds of people, from residents just hanging out on the street corner to young girls having fun to regular workers on the night shift, and I would stay in touch with them by sending them the photos I had taken.

At one point, I realised that there were hundreds of people I’d photographed and I could see that they appreciated the fact that I kept going back to show them new images of themselves, because often in Africa no one bothers to show people the photos that are taken of them. In these other Kinshasa neighbourhoods I saw a world that was full of life; it was a different kind of beauty and poetry.

I wanted to meet people, simple people, and tell stories about simple people in a simple way.

I kept going back and this Couleur Nuit project took shape quite naturally. Still, there were a lot of photos I would keep to myself, and it was my friend Kiripi Katembo (the late Congolese photographer and filmmaker who died unexpectedly in August at the age of 36) who encouraged me, who insisted that I show the photos as an outdoor exhibition. So I first showed the work in a busy part of the city, known as the Boulevard du 30 juin, which bridges some of the crowded, bustling working class neighborhoods and the administrative center of Kinshasa.

So many people came to see the photos, wanting to be photographed next to the photos. I always say that I show what I feel, and see with my heart. I remember spotting a young Congolese woman who kept looking, in amazement, at this one particular photo of an old man. I asked her why she was so mesmerised. She said, ‘Look at his Burberry shirt!’

That, to me, is Kinshasa.

Why did you go down the career path of becoming a documentary filmmaker and photographer?

As a child, I wanted to be a shrink. Psychotherapy was my thing, but of course my parents said I was crazy and those kinds of careers weren’t meant for Africans. So I ended up studying film in Montreal and Paris, and I also graduated from the Institut d’Études Politiques (Sciences Po) in Paris. The political science studies were interesting, and they helped me to gain a better understanding of the world, but I could also see the limits of those kinds of studies and decided to become a documentary filmmaker.

If I didn’t tell those stories now, then I would be leaving behind a part of the person I am.

I wanted to meet people, simple people, and tell stories about simple people in a simple way. Most of my films have a political angle, and at that time I remember feeling that if I didn’t tell those stories now, then I would be leaving behind a part of the person I am. The photos are an extension of this need for documenting, through images, what I managed to see.

Who’s your African of the year?

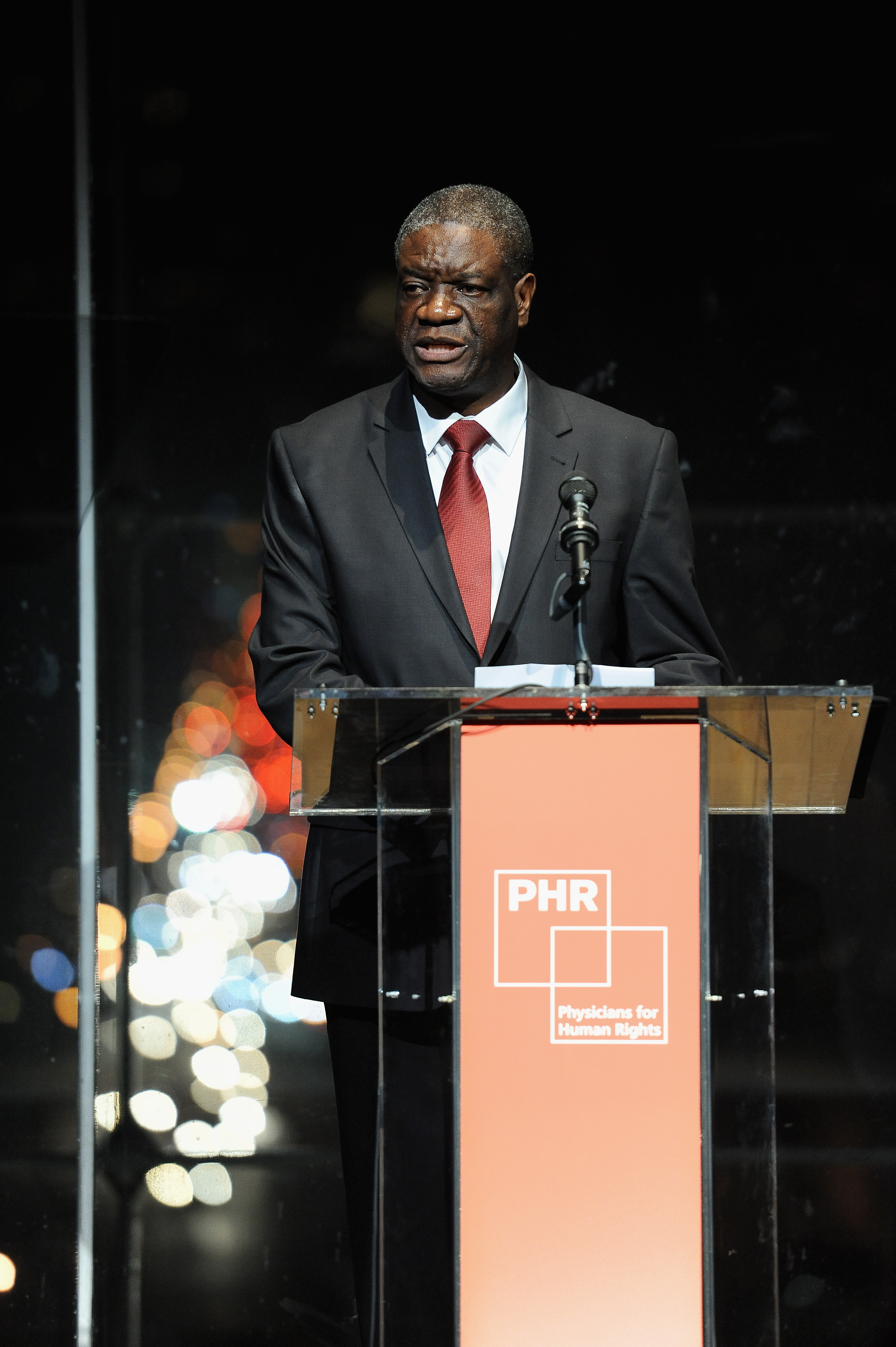

That’s an easy one. I would say Dr. Denis Mukwege, the Congolese gynaecologist who founded the Panzi Hospital in Bukavu. He has treated thousands of women, some who are only 20 or 21 years old, who have been gang raped by rebel forces in the Congo War. He is well known now, but I met him more than a decade ago, when not many people knew who he was. We made a film together, Un Amour Pendant la Guerre, which was filmed in Bukavu in 2003 and released in 2005. The film was about a couple who separated during the Congo War, with the woman moving to the East of Congo (where Dr. Nukwege lives), and the background being the lives of the people in that particular area of the country.

I reconnected with Dr. Mukwege in 2012. By then, he was quite famous. He is an incredible human being, devoting his life to helping these women, but he remains humble and generous at all times. He is courageous. There have been six attempts on his life, and on the last attempt his driver was killed. But he keeps going. He even returned to the Congo after a brief exile in Belgium, his rationale being that he didn’t want to be just another immigrant in Belgium when he could be helping his people. Dr. Mukwege is a very beautiful person.

Congo Couleur Nuit is on show at the Galerie Marie-Laure de l’Ecotais from October 8 to 22.

Follow Osvalde on Twitter @OsvaldeL

Come back tomorrow for the next TRUE Africa 100 and keep up to date using the hashtag #TRUEAfrica