Marwan Zakhem is a Lebanese-born, London-raised, Accra-based civil engineer-turned-entrepreneur who has become a discerning collector of Ghanaian and West African art.

His company, which handles large engineering, procurement and construction contracts in the oil and gas sector, actually developed and built the Kempinski Hotel Gold Coast City, Accra’s most luxurious five-star hotel, which opened in 2015.

When you walk into the lobby from Gamel Abdul Nasser Avenue in the Tony Ridge neighbourhood, everything spells cosmopolitan luxury. The modern African touches are visible in the sculpted geometric lamps standing on the shiny wood coffee tables, and the roof top pool is in the kind of secluded outdoor area where you imagine all the glasses are permanently refilled with exotic sounding cocktails stirred with tiny umbrellas.

The most interesting corner of the hotel is actually a reinvention of the white cube.

Accra can be a very expensive city, and despite the recent slowdown in what was once the world’s fastest growing economy, money continues to flow in an out, with quite a few hundred-million dollar deals negotiated by the Kempinski’s organic food bar. Businessmen are everywhere, but the most interesting corner of the hotel is actually a reinvention of the white cube that seems hidden behind an airy lounge in the left wing.

Gallery 1957 opened in March, but when I visited the space last month ahead of my interview with owner Zakhem and Nana Oforiatta Ayim, the elegant, articulate creative director who pretty much singlehandedly redefines the word ‘Afropolitan’, I was struck by the serenity and cool modernity of the setting.

Everyone pointed him in the direction of Nana.

Marwan, who relocated to Accra from Dakar 12 years ago, met Nana through a mutual friend. When he was setting up Gallery 1957, Marwan kept asking everyone who could be that person to spearhead the artistic vision. Everyone pointed him in the direction of Nana, and the collaboration led to the opening of what was always destined to become an internationally known commercial gallery.

‘I could see that there was a need for such a gallery,’ Marwan said to me when we finally sat down in the lobby that is adjacent to the gallery. ‘And because I am passionate about this kind of art, I felt that we could make it happen, and I could continue to do what I do. It’s about collecting, collaborating, and providing a platform for artists to be able to do what they do.’

He admits that many of the gallery’s visitors are hotel guests, with fewer than ten Ghanaians visiting each day. Nana doesn’t seem concerned with the affluence. ‘Art is a rarefied field,’ she added. ‘And this is true anywhere in the world. You get a full house on opening night, and then not many people after that. I went to the Tacita Dean show in New York (at the Marian Goodman Gallery), and I was the only person there, with my friend. And we were there for, like, two or three hours.’

Still, Nana is deeply committed to expanding the notion of art and reaching out to the wider public. In Gallery 1957 that expresses itself in the creation of public programmes and installations for every show they present at the actual gallery. The idea is to enable more people to see and experience the art.

I think there is a collector base in Ghana, but it’s still very small.

While waiting for the interview, I saw the powerful Serge Attukwei Clottey exhibition My Mother’s Wardrobe in the gallery. The pieces were about to be taken down, and I wondered who the actual buyers were. Marwan says is was split pretty much 50/50, between Ghanaians and international collectors. ‘I think there is a collector base in Ghana, but it’s still very small and needs to be cultivated.’

Nana estimates there are about 20 serious collectors in Ghana, compared to about 70 in Nigeria. She says the focus of Gallery 1957 is primarily Ghanaian artists who are locally rooted. ‘I think going forward it would be interesting to show some of the older generation of Ghanaian artists, the people who’ve been making work for the past 20, 30, 40 years, as well as some of the younger artists following on from those mid-career artists.’

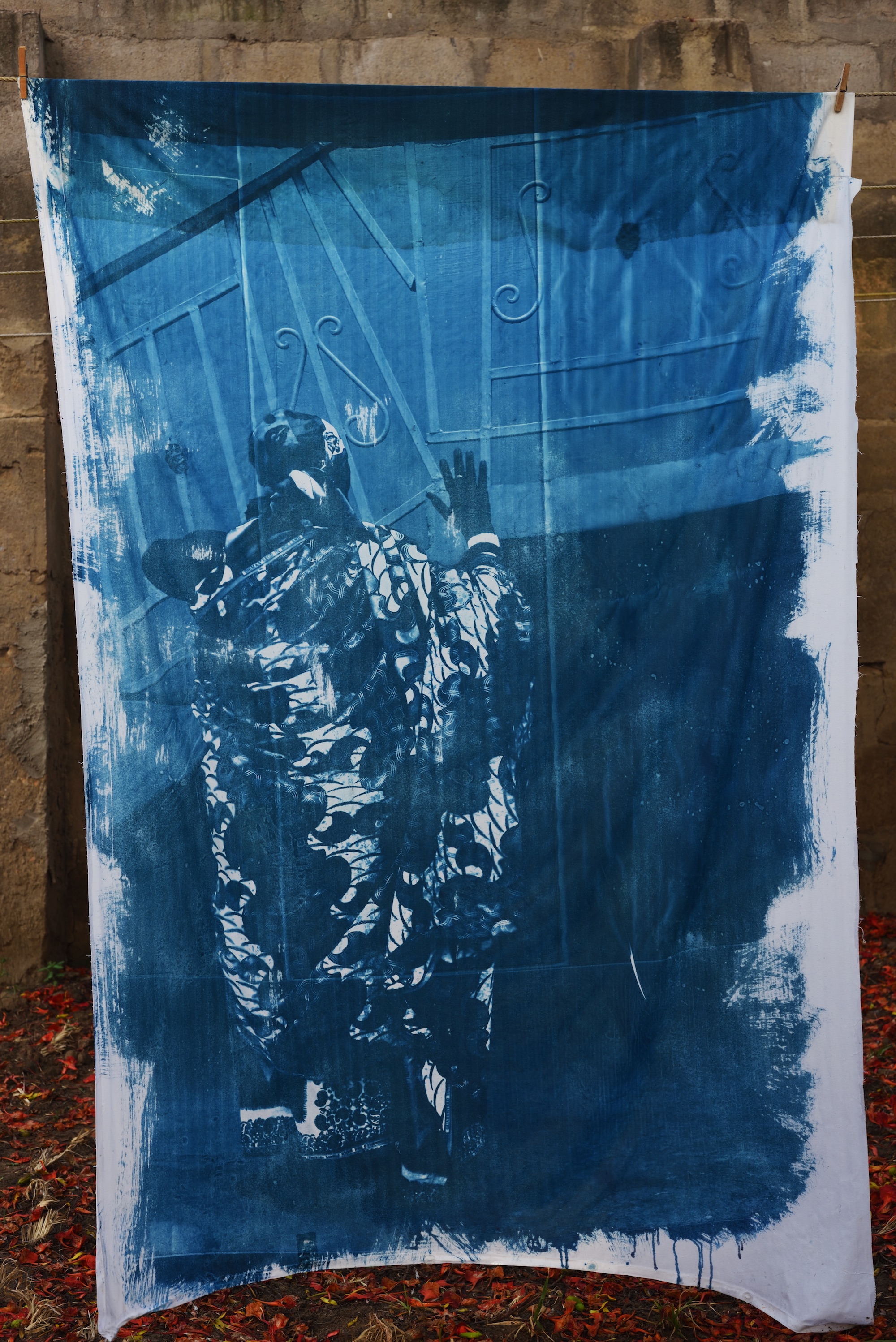

One of the younger — and more versatile — artists both Nana and Marwan seem very excited about is Zohra Opoku, a German-Ghanaian who creates installations and works across photography and video to ‘explore the sophistication of textile cultures in disparate spaces.’ Known for figurative screen-prints, she is currently experimenting with Cyanotype and Van Dyke Brown alternative photo processing.

On the eve of her new show, Sassa, a sun-printed series of Asante Queen Mothers, which opens today at Gallery 1957, we caught up with Zohra in an attempt to find out more about her fascination with what she calls ‘individualistic and societal identities.’

What work are you up to next?

I am sun-printing a series of Asante Queen mothers with Cyanotype and Van Dyke Brown alternative photo processing, which I aim to show at my next solo show in Gallery 1957 in Accra.

When did you start practicing as an artist?

I’ve been practicing my whole life, focusing only on art since the end of 2008.

When did you begin to integrate fabrics into your artwork?

Fabrics always played a main role in my research and installation practices.

Is there a routine in how you decide to compose your photos?

The most important routine is the research of the location which connects the portrait story well to the backdrop.

Was there something that instigated you turning the camera inwards, towards yourself for your self-portrait series?

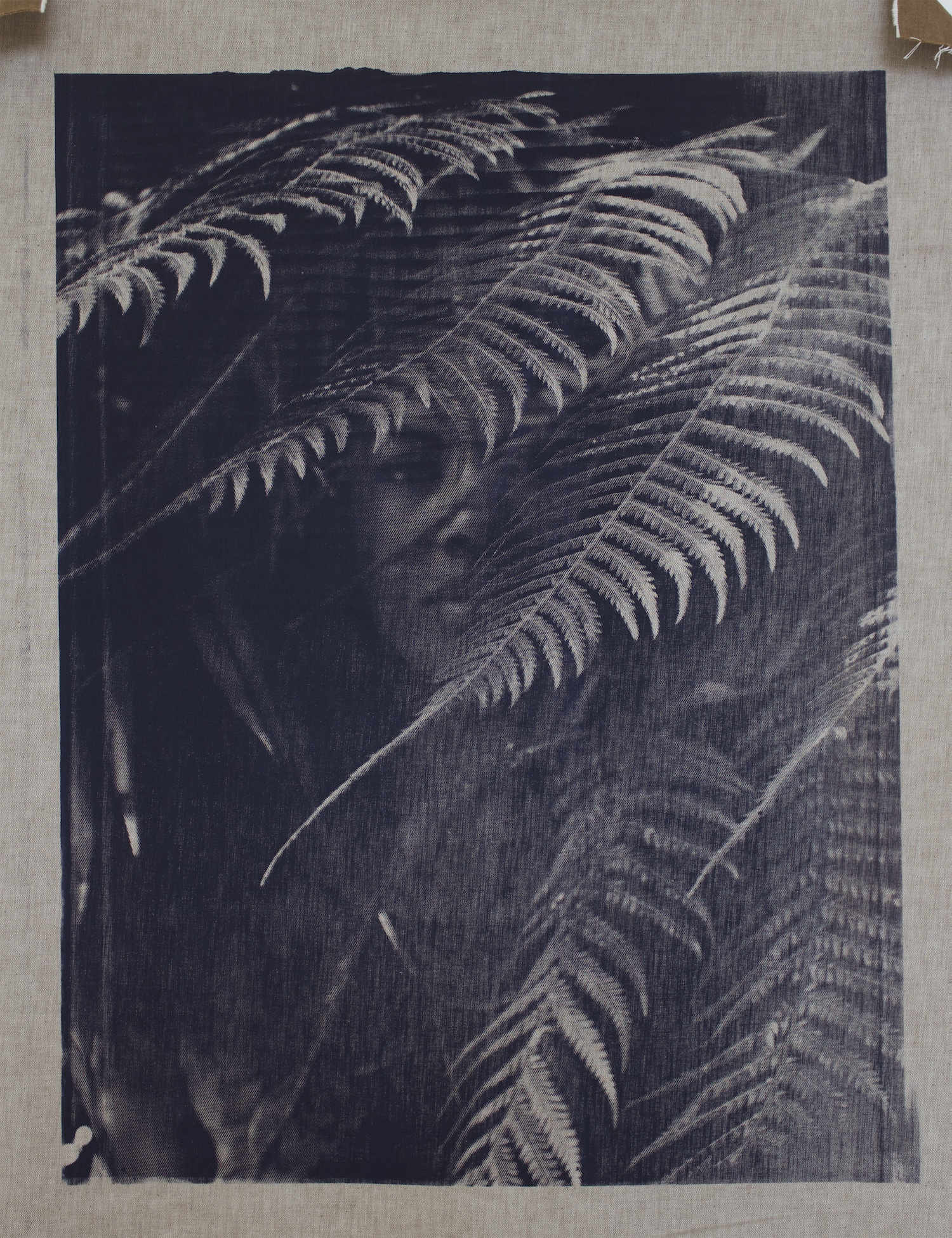

While learning last year about the San Francisco Bay area, my research turned its focus on the diversity of plants. I find it fascinating that there is a huge variety of non-native plants from different climates, brought there and growing in so-called plant communities such as dunes, grasslands and forests. To follow up on my portrait series TEXTURES, I am interested in what is hidden behind an image, disguise and nature are again playing a major role in this work.

Spending a lot of time by myself and contemplating the genre of portraiture, I decided to work in a camouflage self-portrait process. It came to me like a solution at this time; and developed into a therapeutic conversation between the “I” and “me” of which my ego seeks to achieve my self-reflexive identity. Working in this self-portrait process leads me to engage with plants in the bay, which fascinated and inspired me to be like them, making myself a home. By draping myself into them and becoming invisible at the same time allows me into the state of an absolute comfort zone.

Why did you move to Accra?

Moving from Germany to Accra was a long transition through many years going back and forth to Ghana. I moved to Accra because I wanted to discover the other half of me.

Find out more about Gallery 1957 at gallery1957.com