Touria El Glaoui founded 1-54 in 2013, with the original edition taking place in London. Since then, 1-54 has expanded to New York and Marrakech. Last year’s launch at La Mamounia in Marrakech was the first showing on the African continent, and I was impressed by the diversity (and quality) of artists, galleries and collectors who chose to embark on this particular discovery trip. Many of the people I spoke with last year, including several well-known curators and cultural entrepreneurs, were visiting Morocco for the first time.

This week’s edition (23-24 February) will showcase 65 artists from 18 galleries, including six from Africa. Ahead of each edition of 1:54, I always profile an artist who, in a completely subjective prediction, feels to me like the future talk of the town. This year, the 41-year-old painter Amadou Sanogo is the one I am betting on. Three weeks before the opening of his show at 1-54, I was able to catch Mali’s rising star in Paris, where he was presenting some of his recent work at André Magnin’s brand new Magnin-A gallery in the Oberkampf neighborhood.

Located just a stone’s throw from Bataclan, the concert hall where 90 people were killed (and many others injured) in the November 2015 terrorist attacks, Magnin-A is a multilevel exhibition space that was designed to showcase large works in the most minimalistic contemporary art setting. As he proceeded to show me the space, André Magnin admitted that, while converting the basement floors, the main architectural challenge was figuring out a way to replace the functionality of the corners that had been shaped by the previous tenant, an underperforming real estate agent’s office.

I was able to spend some time with Sanogo’s artworks, on a guided tour with two of Magnin’s longtime team members, Philippe Boutté and Cyrille Martin. As soon as we walked back to the ground floor, the artist walked in. I had heard from my friends in Bamako that he started out, after making some noise as a student at Bamako’s Institut National des Arts, painting on repurposed cloth from local markets. Specifically, he chose the cloth used to make Bogolan, the West African textile some call mudcloth. I was intrigued by the fact that he painted over uneven surfaces, as if his ideal canvas was meant to enhance the irregularities in the texture that come from an artisanal process where the textile is woven on looms in rural settings.

In 2003, Sanogo was noticed for a series of paintings that were inspired by Bambara proverbs. Bambara, with its dual lexical tones, is the lingua franca of Mali. Because Bambara is popular with griots (called Jeliw in Bambara) and all kinds of storytellers in Mali and beyond, the fact that a young visual artist would appropriate those particular tonal phrasings and incorporate them into his work was seen by many as a strong tribute to the glory of the old empire of Mali.

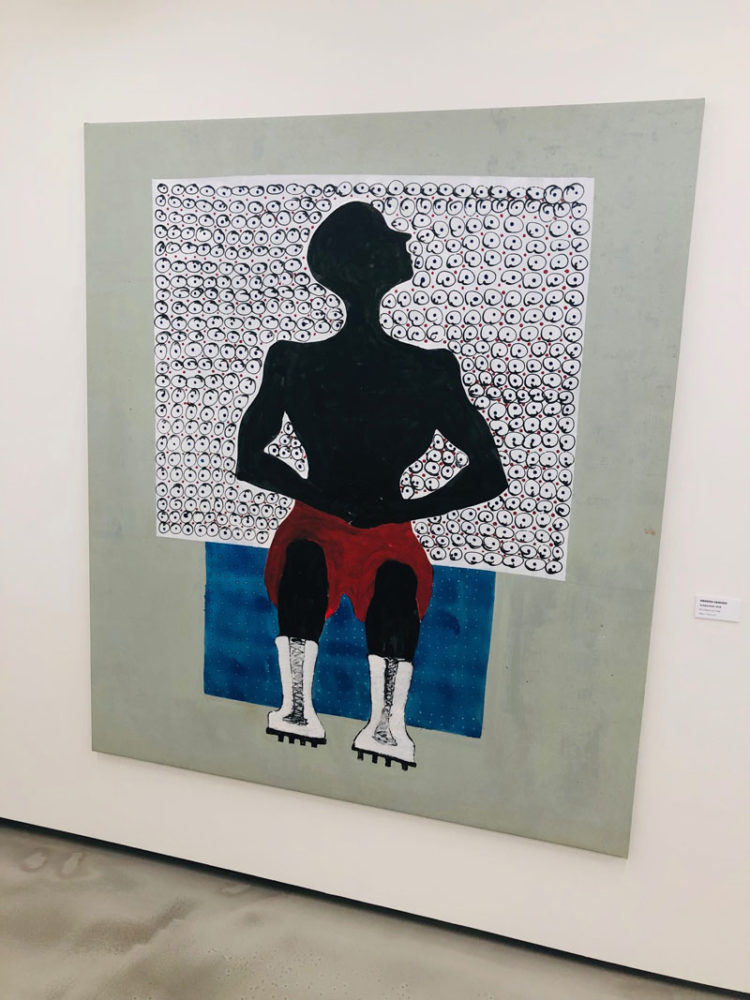

Then, in 2006, Sanogo collaborated with curator Simon Njami and the artist Pascale Marthine Tayou, in a cross-continental exchange that gets noticed by art world insiders. Now, as a new protégé of Magnin—the man known for bringing Seydou Keïta, Malick Sidibé and Bodys Isek Kingelez to wider recognition in the Western world—Sanogo is presenting a figurative style that looks and feels naïve. The contours of the faces and bodies allude to the learning curve of the self-taught, but upon closer inspection it becomes obvious that he benefited from the precision in the academic training that comes with art schooling.

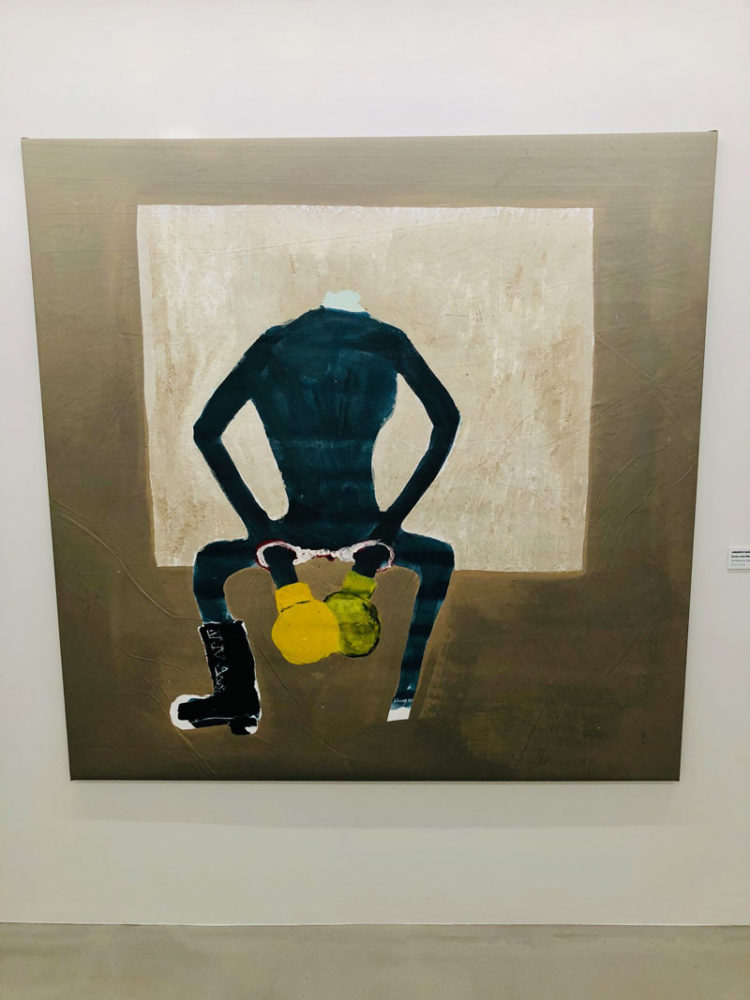

Tracing the evolution of his work over the past decade, one notices that it is becoming increasingly political. The figures in his paintings are not posturing, they are quietly resisting some form of authority. My first question was about what I perceived to be a series of interpretations of what a change force might look like. “It’s very difficult to separate an African’s reality from the reality of African politics,” said Sanogo. “The current severe slump in Africa is a consequence of politicians’ ineffectiveness. African politicians have mastered the art of manipulating the population.”

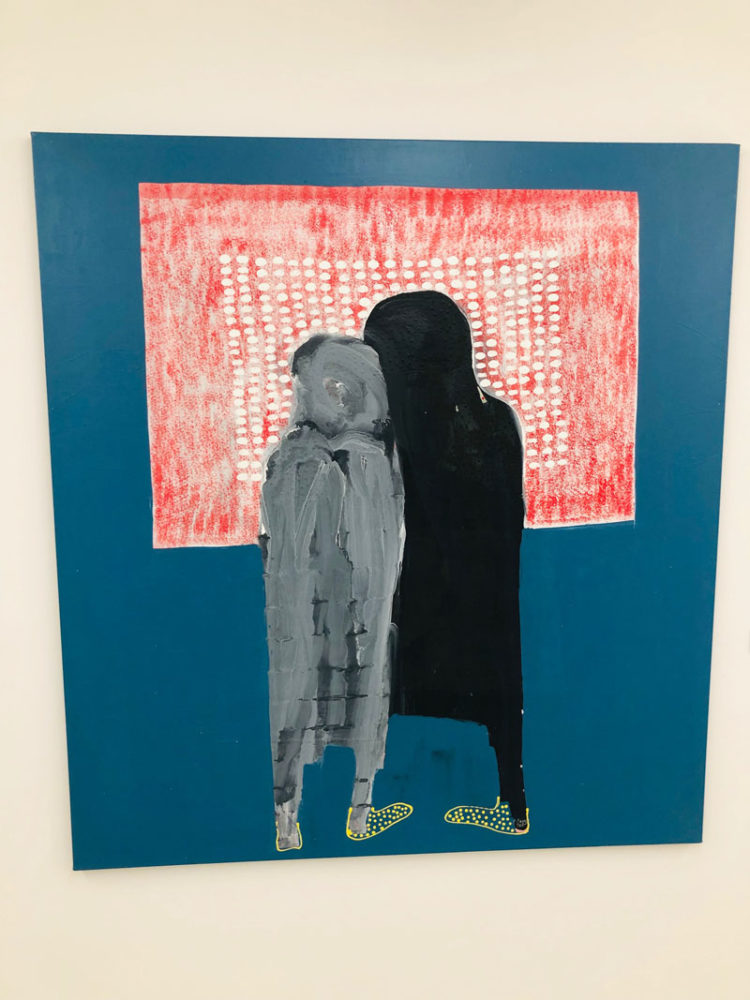

At that point, Magnin felt the need to chime in. “Sanogo is not a big fan of African presidents,” he said. “Look at the way he paints figures wearing spiked shoes.” When I heard that, I started seeing those spiked shoes, visible in works such as Que les bayas parlent, as subtle metaphors meant to tackle those African heads of state who refuse to give up power. Instead, Sanogo told me that those spiked shoes have a different meaning. “I’m inviting Africans into combat, which is nothing more than refusing to give up.”

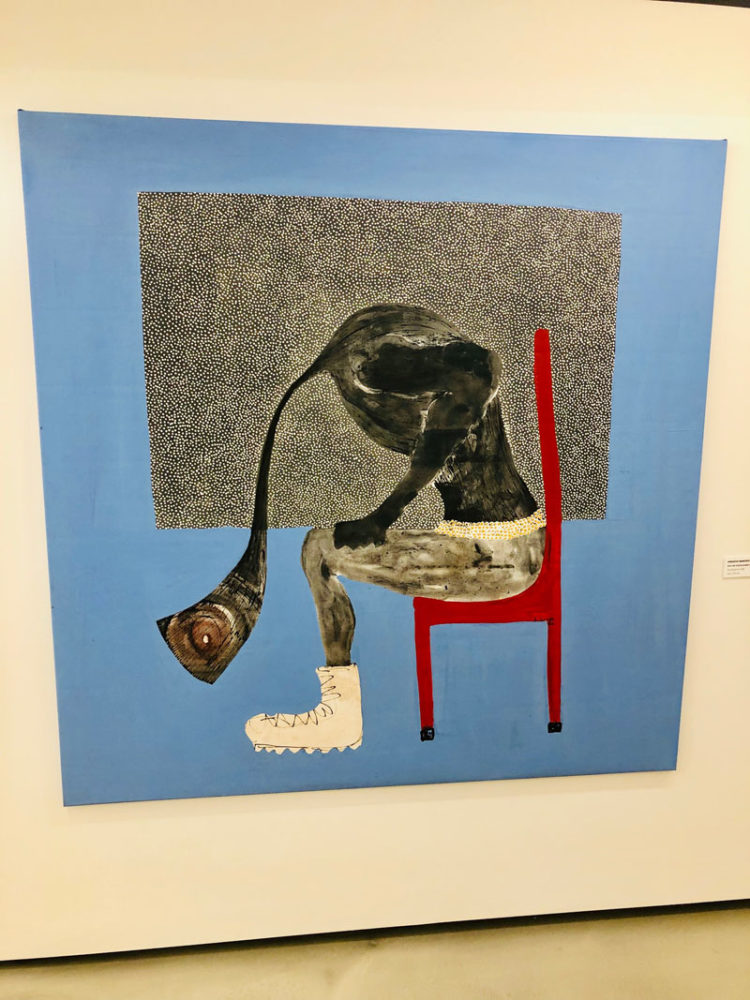

Much of the subtext in Sanogo’s work seems to be a fight for liberation. I was particularly drawn to the headless boxer painted in acrylic in the 2017 painting Boxeur sans tête. “The headless series came out of a visceral reaction I had to some leading figures in Mali. They keep showing us their power and status, but in fact they’re not saying anything or coming up with any new solutions that would benefit the people. Leaders, politicians and intellectuals, they are meant to come up with proposals, but what I keep seeing is politicians who cling on to privilege, and intellectuals who brandish their degrees. If everyone says quiet, nothing will change.”

I wondered whether these characters were real, or purely imaginary. “I just see what is happening in our daily lives,” he revealed. “And I try to imagine environments, in my own way.” As far as imaginations go, Sanogo’s 2015 painting Les Observateurs feels, to me, like his most powerful statement, so far. “The idea of this couple came to me during the private view of an exhibition I created with my Atelier Badialan artists collective in Bamako. The couple just stood in front of one of my paintings, and started cuddling, as if they’d forgotten that they were in a public setting. I tried to capture the rapture of that moment with Les Observateurs.”

Sanogo was born in Ségou, south-central Mali, into a Senoufo family. As an ethnic group, the Senoufos are known for their handicrafts, as well as for their innovations in music, even though most of them work as farmers. Speaking with Sanogo, and hearing his references to Senoufo traditions, one feels a connection to the soil of his ancestors, and to ritual objects. He remains grounded, particularly in the way he describes his apprenticeship, as if it were always meant to lead to simple, homegrown, unpretentious artistry.

Several of Sanogo’s paintings that will be shown at 1-54 feel unfinished, crafted to remain works in progress. “That is intentional,” Sanogo told me. “These works are meant to be that way, because I adhere to the Bambara philosophy that says perfection doesn’t exist. I find it incredible that, as humans, we are always striving for perfection, even though we can never attain that perfection. In order to even begin to understand what perfection means, we must accept who we are, with our flaws.”