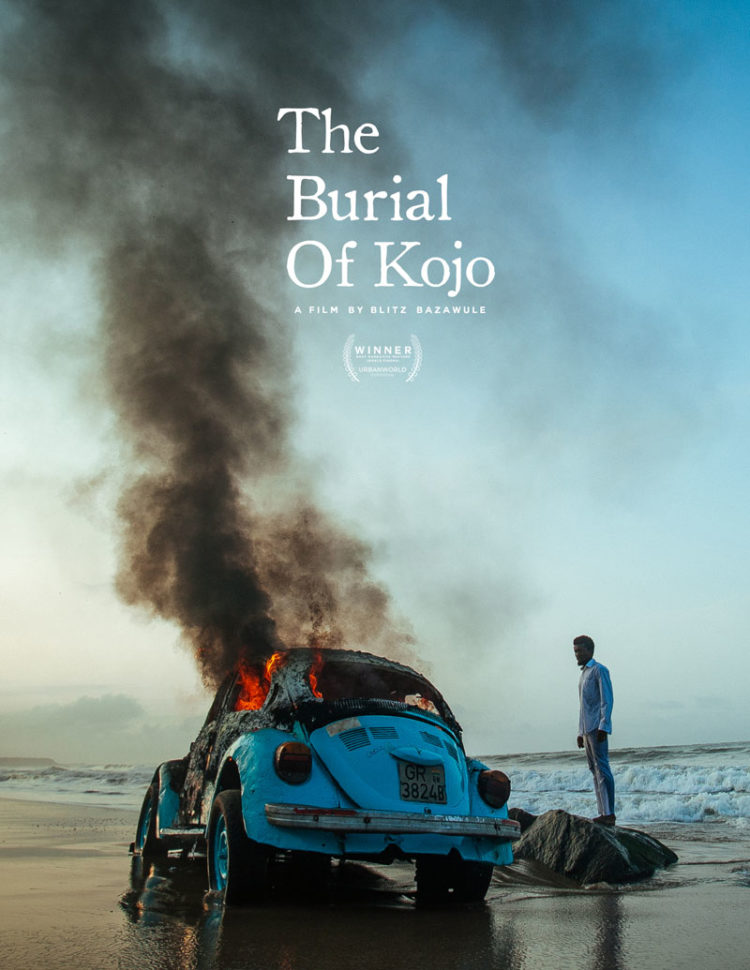

The Burial of Kojo, which was released earlier this month on Netflix, is Blitz Bazawule’s critically acclaimed debut feature. Hailed as a triumph of visual experimentation where fantasy and reality find ways to overlap through Ghanaian rituals, it is the story of a young girl, Kojo’s daughter Esi, who endeavors to understand her father’s tragic past. Also known in the music world as Blitz the Ambassador, the 36-year-old Brooklyn-based Ghanaian musician turned filmmaker was also selected as one of the artists for the 2019 edition of the Whitney Biennial, which opens at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York on May 17th. We sat down for an interview at the TED Conference in Vancouver, which Blitz attended as a TED Fellow.

At TRUE Africa, we’ve been following your Burial of Kojo journey, from the moment you announced the film project, all the way through crowdfunding and other types of creative fundraising, when you were trying to make this film a reality. What was the most difficult part of that journey?

I think it was communication. Anything related to Africa is always a communication issue. Are you communicating the work itself? Are you communicating its profitability? Are you communicating the fact that anybody wants to see it at all? Those were all the early challenges for me. If you’re in the community, you know that the answers to all these questions are yes, but the work itself has to have its own internal communication. So once I realized that nobody was going to give me any money, because there was no amount of communicating that was going to convince anybody, then I started looking inward, and I think that was when the game changed, because I’ve been working for a very long time on communicating Africa. To Africans and to the world.

My ten-year foray into music was all a communication boot camp, right away, in order to understand how one frames Africa, domestically but also internationally, especially when dealing with people who misunderstand Africa. It’s like you have to ignore them, and eventually they come around. That’s where The Burial of Kojo ended up getting to, where the work just had to exist, and we had to have already communicated it. In a way, just by doing that the world was forced to come over.

One of the things that I find particularly challenging with those kinds of projects is, with you coming from a Ghanaian perspective, and also from a Brooklyn perspective, how do you make a film like The Burial of Kojo relevant to an audience that is spread across various communities around the world, whether it’s Brixton, or here in Vancouver, whether it’s in Africa or in the African diaspora?

It starts from specificity. I think we were lied to when we were told that you have to have a universal story. That is false. Actually, the more specific we are, the more universal we’re being, because everybody is derivative of us, globally. Whether we know it or not, our genetic memory remembers. My thing was always, start first internally. My first job was to communicate with Ghanaians in a specific space. Once I was done with that, my next job was to communicate with African diaspora folk, whose genetic memories are a lot closer to ours. And then, naturally, I did that cross-culturally, then racial diversity comes in, background diversity comes in, because you started specific.

That’s the kind of work I did with music, that’s really what the work was. The work was to travel the world, to identify how we all speak to each other, to identify the African-ness that is across the globe, and to find the elements that intersect. Now, not everything intersects with Africans and African Americans. Not everything intersects with Afro-Brazilians and Afro-Latinos. But on the flip side, a lot of things do intersect. Then the question for me was simply finding those intersections, and through those intersections I’ve made music for a decade. So a lot of times I find myself relying on some transferable knowledge, because it’s literally the same thing, communicating to people who have seldom been communicated to.

A lot of my work also required me to move physically to these places. I took the film to Brazil specifically, and in places like that I identified what the African diaspora was, because not every place black people are also has self-determination. If you find black Africans in the UK, there’s a level of self-determination that you can work with. Africans in Brazil are coming into their own. Africans on the continent have always been trying to assert themselves. Africans in America have always done that.

I was trying to pack that together, and I arrived at a kind of fluid language that we all speak, because we all speak strong visuals, we all speak vivid colors, we all speak spontaneity. That’s why jazz is so similar to afrobeats, is so similar to funk. It’s the same language. That’s what I was able to deduce, and once I figured out that that was the highway you build this thing on, it became easy, because once you start cruising that you realize that the world always come where we are. If 20 black people just gather right now, the whole of TED is going to be curious, wondering what’s cooking. Is somebody going to flip this thing? We don’t know what’s going to happen, because it’s magic, because that’s our gift to the world. So that’s how I view the film, and it’s been super successful.

This highway that you’re on, this communication and this community that you’re on, to use some of your own words, is what I call transcultural, because you’re operating across continents. You’re also a global African that is operating in music, in film, and also now in art. How do you view this new type of artistic expression, from your global African perspective?

Well, I think that’s another thing that is quintessentially African. Our art is fluid. Our art has never really been put into specific boxes and specific categories. When an African percussionist is playing, he’s not just making music. It’s performance art. It’s also visual art, depending on the space. I started out as a visual artist. I drew, I painted, I transferred to music, I transferred to cinema. I feel like that fluid stream is also going to be one of our biggest assets. It means that we are fluid in a way that, when we create work, immediately it is proliferating on multiple levels, and it’s communicating on multiple layers.

Making The Burial of Kojo, I was also making a score, which is very significant because folks are listening to the music, which is communicating separately from the visuals, and communicating separately from the visual art elements. We also created some still images, the photography that came out of the film, and that will also be exhibited later. So out of one work come multiple conversations.

The real question is, how many portals can you open into your work? I may be excited about the visuals, you may be excited about the sounds, she may be excited about the other layers that have been put into the work. When we get to communicate on multiple levels, I really encourage my peers to see that as an opportunity and to never look at ourselves from this very myopic Euro-normative lens of creating work that fits into a neat little unit and box. When art is fluid, it’s our one true liberator, which allows us to communicate, first to ourselves and then to the world.