When I was a child growing up in late-seventies Lomé, I would stay up late on those Saturday nights when my parents threw ‘surprise parties’ on the patio.

I can remember everything about the way our Togolese madames in boubous would get down on the dusty dance floor all the way to the tip of the pointy shoes sported by their overstyled Chivas-drinking husbands. Because I’ve always been a bit of a people watcher, I noticed that Independance Cha Cha by Grand Kallé and Miriam Makeba’s Pata Pata were the crowd pleasers that got the party really started.

A young — and curious — observer of adult misbehaviour, I can trace my love of music to those alcohol-fuelled soirées, my earliest childhood memories. A lot of new moves were improvised around the imported Afro-Cuban jazz harmonies, and every so often my father would get drawn into a Johnny Pacheco challenge. When he lost — he was usually outdanced by my hip-shaking uncles — the vinyl could be switched to Rendez-Vous Chez Fatimata, the catchy Cuban-infused tune by the Maravillas de Mali.

Fast forward 35 years to the magnificent exhibition ‘Swinging Bamako’ at Les Rencontres de la Photographie in Arles, a respected photo festival held every summer in the Camargue region of Provence. When I met Richard Minier, the French co-curator of the exhibition, he came off as an encyclopedia of sixties Malian youth culture, commenting on each individual photograph on the walls. It was the Sunday after the private view, and he couldn’t stop talking about why he decided to spend the last 17 years of his life chasing the story behind the Maravillas, a group of young Malians who were sent to Cuba, on a musical learning expedition, by the régime of Modibo Keïta, Mali’s first president.

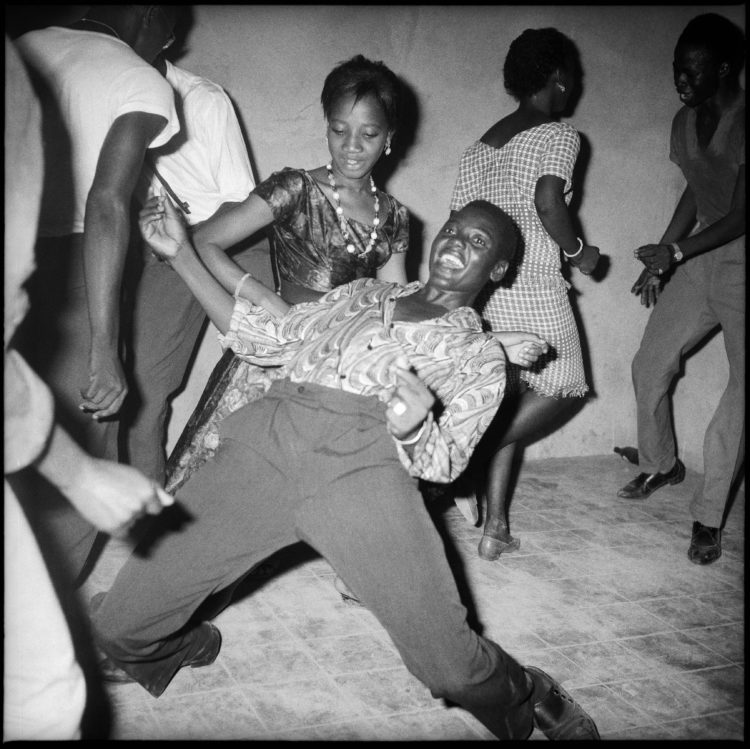

Minier gave me a full tour of the exhibition, which started with some black-and-white party photos from Malick Sidibé’s twist period. None of these now famous portraits (signed by the master, who died in April of this year) were taken in Sidibé’s Bagadadji studio in downtown Bamako. Mostly, they were snapshots of young Bamako denizens listening to music and having fun at weekend surprise parties that were not unlike the ones I snuck into as a child. Just like in Lomé, everyone in Bamako was posing, and photo titles like ‘Regardez Moi’ (Look at Me) from 1962 speak to the new sense of pride that came out of the music that fed the optimism of the early independence years.

‘I was interested in how Malians were so proud of their president Modibo,’ said Minier. ‘When you see some of these photos, you notice that these young Malians felt a need to have Modibo’s face printed on the wax fabric they chose for their matching outfits.’ Modibo was a leader of so-called African Socialism, and he sought to build bridges not only with members of the Non-Aligned Movement, but also with socialist revolutionaries like Fidel Castro and Che Guevara.

One of the highlights of ‘Swinging Bamako’ is the wall that displays rarely seen official photos of Modibo Keïta posing, right when the Cold War was simmering, with prominent Asian Communist leaders like Ho Chi Minh, Kim Il-sung and Mao Zedong. Ultimately, many historians feel that Modibo, a direct descendent of the founders of the Mali Empire, was just a realist who sensed that young Africans could gain knowledge and emancipation by affirming their third-world identity and forging alliances with nations that understood that there could be a new vision for a united Africa.

Richard Minier was reporting for the French daily Libération in Mali when he stumbled upon a story that led him to chase down the last surviving members of the Maravillas. His journey, which took him from Mali, to Niger, to Côte d’Ivoire, all the way to Cuba, started making sense once he met Boncana Maïga, a native of Gao in eastern Mali who ended up becoming the de facto leader of the Maravillas.

A friendship was born, and when I interviewed Maïga and Minier together in Paris a few days after seeing the ‘Swinging Bamako’ exhibition in Arles, I realised that Maïga has shared many of his early adulthood memories with Minier. ‘We were young,’ said Maïga. ‘Initially, there were ten of us who went to Cuba, but some were sent back to Mali because they weren’t good enough, or weren’t working hard enough. At first, I didn’t know the other musicians, because I wasn’t from the same region as them. We had all met for the first time in Bamako before we took off for our trip to Cuba.’

Minier took over the storytelling from there. ‘You have to understand that the state of Mali had organised a nationwide competition, where everyone had to write an application letter. The competition took place in December 1963, and the ten original music students were drawn from six different regions in Mali. When the young men were granted scholarships and sent to Havana in January 1964, the idea was that they would come back to their home country, and teach music to young Malians. Boncana was a bit more famous than the other members, because he’d already started his own band, Negro Band, in 1959 in Gao. Once they got to Havana, they were greeted by a bunch of Cuban apparatchiks and got to spend one month in the Hotel Riviera, then one of Havana’s chic hotels. After that, they were sent to the Alejandro Garcia Caturla Conservatory, a top institution in the Cuban capital.’

The story of the Maravillas, from formation all the way to the recording of Rendez-Vous Chez Fatimata in 1970 that preceded the band’s dissolution (and Maïga’s subsequent successful solo-career as an artist and producer) is being brought to life as a record (to be distributed by Universal Music) and a feature film that some are already calling the next ‘Buena Vista Social Club’. Regardless of how the film comes out, it is sure to capture the energy and melodies of young Bamako in the ‘swinging sixties,’ as influenced by the infectious rhythms of post-revolutionary Havana.

Les Rencontres d’Arles is on until 25 September 2016. Find out more about the Swinging Bamako exhibition here