Last Saturday night, I was walking home from dinner in New York City’s West Village. I’d just enjoyed a nice Italian home-cooked meal at a friend’s apartment, and on my way to meet my Uber driver a few blocks away I stopped by the entrance of Lenox Health Greenwich Village Hospital.

Every time I walk past that hospital, I remember the old Saint Vincent’s Hospital, which used to stand right across the street from what is now Lenox Health. I’d spent part of the night of 9/11/2001 there. Saint Vincent’s, which used to treat Greenwich Village’s literary and artistic types as well as all kinds of vagabonds, closed in 2010, and was demolished in 2013.

I will never forget the night ahead of 9/11, and the way the doctors and nurses treated us after we waited in line for three hours. I had come in the middle of the night with someone I barely knew, a young man who’d been injured at one of my Trace Magazine parties earlier in the evening.

Hours after we were sent home after he was treated, the terrorist attacks hit the Twin Towers, and the good people of Saint Vincent’s had to welcome so many injured that they also started collecting pictures of the missing, which they displayed outside the hospital in a Wall of Hope and Remembrance, which was maintained for years.

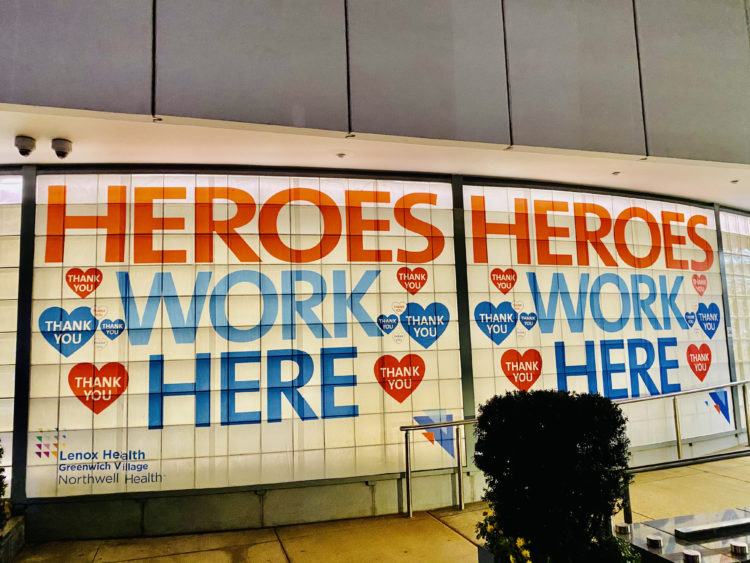

Before I got into my Uber, my fondness for Saint Vincent’s – and the sad memory of 9/11 – led me to take a photo of the wall by the Lenox Health entrance. The big red-white-and-blue letters read “Heroes Work Here. Thank you.” I took that thought with me as I went home and went to sleep.

The next morning, I started feeling chills but thought it was just the fatigue that came with having traveled to and from Costa Rica on a short trip earlier in the week. On Monday morning, I went to work, but for the first time I felt shortness of breath after climbing the five flights of stairs. I’m a runner, so I’m normally never short of breath.

Something was off, so at 6pm on Monday I called a family friend, Dr. Sylvie de Souza ViBi, the Chair of Emergency Medicine at The Brooklyn Hospital Center. I’d been reading and hearing great things about Brooklyn Hospital since the pandemic started, and we published two TRUE Africa stories on the heroic work her team has been doing since the coronavirus rolled into the City’s boroughs in February, like an invisible fog.

She told me to come in straight away. After I filled out the paperwork at the front desk and got a temperature check, 102 was enough for them to keep me in the hospital. After checking my other vitals, the nurse informed me that the pulse oximeter indicated my oxygen level was between 96 and 99%. Below 94% is when they really start to worry, she told me.

In short order, the chest X-rays revealed that I had bacterial pneumonia, which in itself was a pretty strong indication that I had Covid-19. I was sent to a room on the seventh floor of the hospital, and the tests continued. I was not really in respiratory distress, but even before the official Covid PCR results came in, the doctors got proactive and I was given several intravenous drugs, including Remdesivir, the inhibitor that was identified earlier this year as a promising therapeutic candidate for Covid-19.

For the pneumonia itself, I was given Azithromycin, an antibiotic that is widely used to treat chest infections. I went to sleep on Monday night, looking out my window and wondering how I could have ended up in hospital. For the longest time, I remember bragging that I’d never spent a night in hospital, save for my short time as a guest when my wife gave birth to our son Jazz in Lenox Hill Hospital three years ago.

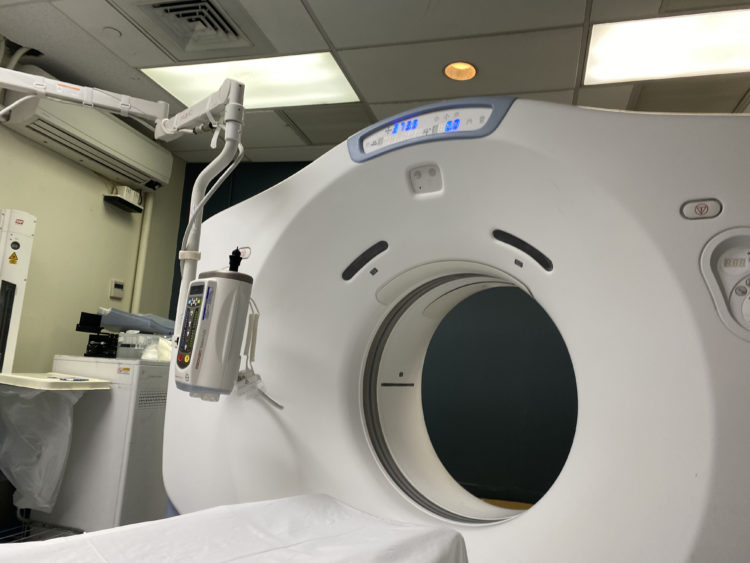

I was woken up by my nurse early on Tuesday morning, for my second set of intravenous injections, and later I was told by one doctor that my official Covid PCR result wouldn’t arrive till afternoon. Still, he said, they were almost certain that I had Covid, and they had made the decision to treat me for it, because my CAT scan had produced 2-dimensional images that all but confirmed that I was in bad shape.

After the doctor left, I looked out the window again, and this time I saw children walking with their parents across Fort Greene Park. The foliage was beautiful, and my room with a view made for delightful fall leaf-peeping. I could sense from their interactions in the park that some parents were nervous, because their kids were out of school, and as parents they had to find ways to keep them occupied after New York’s public school system shut down last week.

Before I knew it, an hour had passed, and it was time for breakfast. Because I’ve always been a bit of a people watcher – I guess that is why I became a journalist all those years ago – I chose to strike conversations with everyone who entered my room. One Caribbean nurse looked at my plastic bracelet, and said “Stop!” Stop what, I asked her. “My son was also born on February 28th,” she told me.

Does he like to read all day the way I do? I told her I was already 100 pages into Barack Obama’s book A Promised Land. My question was facetious. “Oh no, he doesn’t. All he does is play with the computer, and I don’t think he gets paid for it, either.” In listening to those stories, to their anxieties, hopes and frustrations, I got to learn a bit more about the current mindsets of New York City’s essential healthcare workers. Most of the nurses who cared for me are Black.

The night had been strange, because one of my neighbors on the seventh floor chose to keep yelling in the middle of the night. I could sense that, each day as they took care of sick patients like myself, these healthcare workers were finding new ways to juggle the pressures at the hospital with the need to provide for their own families.

My Covid PCR test came in positive, and right after the doctor delivered the news, another nurse came in. I felt concerned that she would be so directly exposed to the virus, to my virus. She would have to worry about endangering her own family. She pulled out the syringe and, with a big smile, looked for one of my thicker veins. I asked her if she lived in a congested neighborhood. “Oooooh yes,” she answered.

I knew that a record number of Americans — 90,000 — are now hospitalized with Covid, and that new cases have been climbing to nearly 200,000 daily. I’d overheard some doctors in the hallway saying this winter would be really terrible, because of all the new Covid patients coming in after Thanksgiving and Christmas, and so I asked my nurse if she was afraid she’d get Covid, and bring it home to her own family.

“Oh, I already got Covid,” she said, without batting an eye, seemingly excited about a particularly promising vein she’d spotted in my right arm. As the pandemic continues to hammer cities, communities and hospitals across the world, not enough attention is paid to the mental well-being of those medical workers who chose such a dangerous line of work.

The New York Times reported earlier this week that “Surveys from around the globe have recorded rising rates of depression, trauma and burnout among a group of professionals already known for high rates of suicide. And while some have sought therapy or medications to cope, others fear that engaging in these support systems could blemish their records and dissuade future employers from hiring them.”

On Thanksgiving morning, three doctors came into my room, and told me that I was going home. They told me that I no longer had any of the Covid symptoms, and that I should just continue the antibiotics and blood thinner treatments at home. Isolation was required until December 4th, and rest is what I needed most, they said.

I looked out my window again, staring at all those small alleys in Fort Greene Park. I know those alleys well, because I used to love jogging there on Sunday mornings back in the day. Despite the warm weather, the park was emptier than on previous mornings. I saw three homeless people, all Black men who seemed to have nowhere to go on the holiday. I said a prayer for them, for Dr. de Souza, and for the wonderful medical personnel at the Brooklyn Hospital Center. They are doing God’s work.