As dozens of U.S. cities—and neighborhoods like mine in Lower Manhattan—brace for another night of protests over the death of George Floyd, I cannot stop thinking about Aleshea Harris’ play What To Send Up When It Goes Down, which I saw with a (white) friend back in January at New York’s Public Theater.

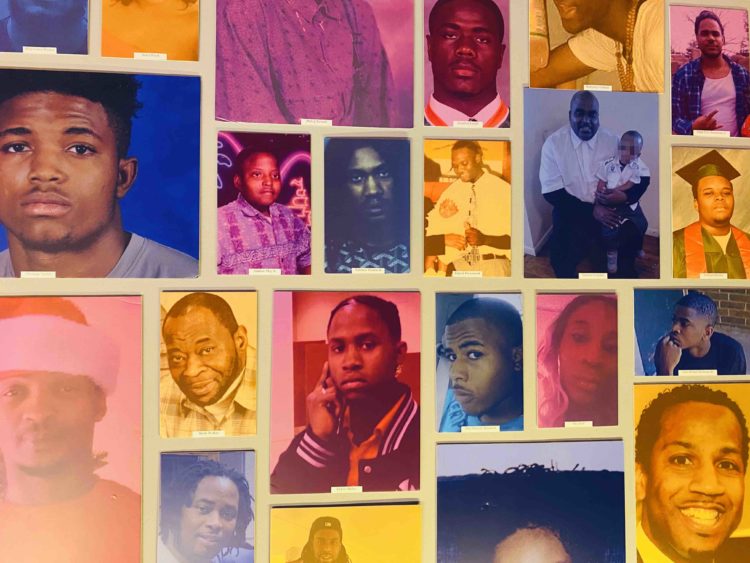

The hallway leading to the actual theater was decorated with more than 200 portraits of African Americans who had been killed as a result of police violence. The play, which is preceded by a warning from a greeter that the themes explored are meant primarily for black people, bills itself as a response to the “physical and spiritual deaths of black people as a result of racialized violence.”

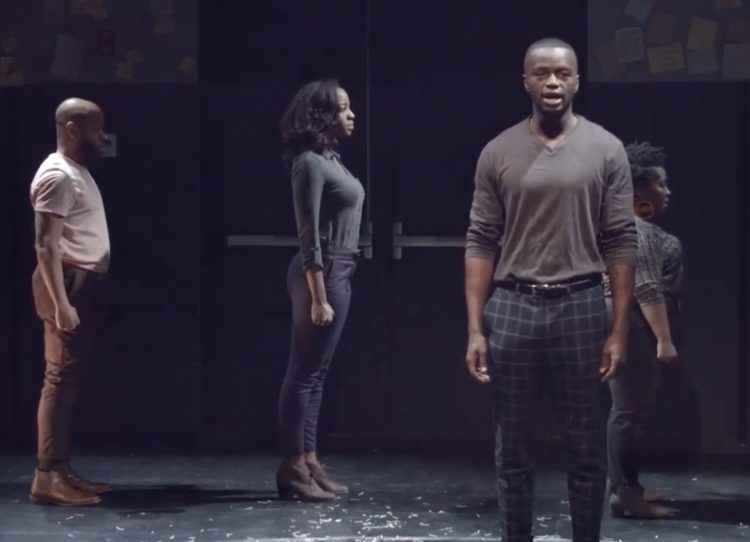

Once inside the theater, a master of ceremonies asked us to form circles, and to repeat the name of a young black man who had been killed in yet another example of police brutality. By now, some of the names are sadly well known. Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin and so many others. I cannot remember that particular man’s name, but there was something powerful about the entire audience repeating that one victim’s name one time for each of the years he was alive.

After that initial call and response, we the audience were asked to participate in a series of vignettes relating to black life in America, and the exercise turned into a ritual that led to a better understanding of the systemic racism that has long defined America as a country. We were asked to yell and scream, and it felt cathartic. It actually felt good every time we expressed those feelings of anger. Right when the play was coming to an end, the master of ceremonies politely asked non-black audience members to make their way out of the theater.

Those of us who were allowed to stay—black people of different complexions and nationalities—were asked to reflect on the state of our community and enjoy a moment of kinship. It was an honest (and unforgettable) moment of solidarity, and some of us shared our personal feelings about black rage, feelings we could never share with people who aren’t black, with people who could never know what it feels like to live in black skin in a country that was built on inequality and white supremacy.

When we left the theater, I asked my friend—her name is Courtney—if she felt that the master of ceremonies had acted in a racist or insensitive manner in not allowing non-black people to experience the play’s final act. She told me that she was not offended, not at all, and that on the contrary she “got” what the play was about. She said she understood why that decision was made.

I was surprised at her reaction, because I could tell that it wasn’t a politically correct answer. Nor was it a knee-jerk white guilt reaction. Mostly, I was relieved, because, over the years, I’ve found myself in countless situations where I just gave up on trying to explain to my white friends what actual (and not perceived) racism really feels like.

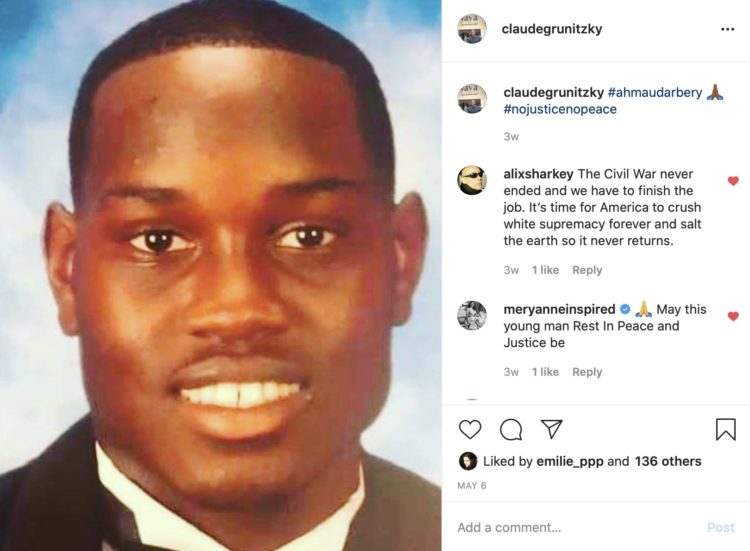

In the age of social media, I’ve occasionally used Instagram and Facebook as tools to express my views on society’s ills. As a general rule, I don’t post very often, because I’m not that kind of activist, and I try not to preach, but a few weeks ago, I felt compelled to share that now famous photograph of Ahmaud Arbery, the 25-year-old black man who was chased and killed by white residents of a middle-class Georgia neighborhood.

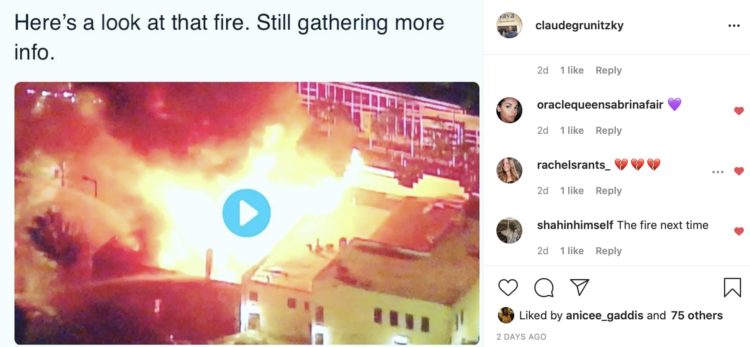

I remember posting during the Ferguson protests, back in 2014, because I could sense that Michael Brown’s death would end up launching an important national conversation about police brutality, but when I posted a photo of the fire at the Minneapolis station earlier this week with the hashtags #georgefloyd #blacklivesmatter and #nojusticenopeace, I knew that many of my friends would stay silent, precisely because they hadn’t yet fully formulated their thoughts on the riots and what they mean for America.

One of my friends who did comment is a Paris-based black French economist. He posted just four words, “The fire next time.” Despite the pain and frustration many of us felt all week as the full story of George Floyd gradually came to light, I was excited that the title of James Baldwin’s seminal 1962 essay (which in so many ways personalized the history and the issue of black oppression in America) made it into my Instagram feed.

The first essay in The Fire Next Time is “My Dungeon Shook—Letter to my Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation.” Reading between the lines and making sense of the epistolary bond between two black souls of different generations, the reader understands after reading that first essay why Baldwin chooses to dissect the history of race relations in America and make that history accessible to those who know nothing about America.

Baldwin asks the reader the following question: “How can one respect, let alone adopt, the values of a people who do not, on any level whatever, live the way they say they do, or the way they say they should?” I read The Fire Next Time when I was 23, and as a Paris-bred Togolese immigrant in America, I often thought about that question, and by the time Barack Obama was elected in 2008, I chose to become an American citizen myself because I felt that the promise of new America was greater than the scars of slavery and segregation.

At the end of “My Dungeon Shook” Baldwin writes to his nephew: “This is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what America must become.” As a black man who moved to New York as an ambitious 27-year-old media entrepreneur who was fully convinced that he could do great things in America, Baldwin’s optimistic view of a future America, which I would later couple with Obama’s “Yes We Can” messaging, gave me hope for America, and for my own future.

In July 2016, my cousin Olivier Grunitzky and I hosted a small dinner for Opal Tometi in Olivier’s Paris apartment, near the Eiffel Tower. Tometi is the Nigerian-American human rights activist who is best known as one of the three co-founders (alongside Alicia Garza and Patrisse Cullors) of Black Lives Matter. I remember that dinner as being both fun and frustrating. Essentially, that dinner could be summarized as a series of disagreements, mostly because I could sense that Tometi felt that I didn’t really understand the complexity of race relations in America.

I remember feeling quite offended at the time, because my view was that you didn’t have to be born or raised in America to understand what black America was. Being black was enough, I thought. And Obama was making things better for most Americans, and for most black people, I argued. Nearly four years after that Paris dinner, I realize that I was wrong, and that Tometi might have been trying to explain that one cannot really fully grasp the true experience of modern American racism unless they came of age as a non-white person in America.

Michael Brown was just another unarmed teenager when he was shot and killed in Ferguson, Missouri, by police officer Darren Wilson on August 9th, 2014. The Black Lives Matter grew out of that moment, and I now understand how the pent-up anger must be so much greater for those who grew up in America’s black communities with the knowledge that too could be killed by the police in their own neighborhoods. At times, it could just come down to being at the wrong place at the wrong time.

There were a few examples of police brutality in some of the rougher greater Paris neighborhoods when I was growing up, but straight up first degree murder by a police officer was extremely rare, and no French police violence statistic was ever as chilling as the one that confirmed that, over the course of a lifetime, black men in America face a one in 1,000 risk of being killed during an encounter with police, as reported in an August 2019 study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America.

I am watching the images on my phone again, and tonight is proving to be yet another night of unrest all over America. The death of George Floyd at the hands of the police may well change America. Let’s hope it’s for the better. As I reflect on my 2016 conversation with Opal Tometi, I realize that I will never know what it is like to grow up black in America, in the same way that my friend Courtney and all the other non-black people who were asked to leave the play What To Send Up When It Goes Down will never know what it is like to live in America as a black person.