The Parisian auction house Piasa, which focuses on art and design, has appointed writer and curator Olivia Anani and Sotheby’s alum Charlotte Lidon co-directors of their Africa + Modern and Contemporary Art Department.

The appointments are significant, because they speak to long overdue management reforms at several top European cultural institutions. Many museums, art fairs and auction houses had stated in the past that they wanted to increase diversity within their ranks, even at the level of the most high-profile positions, but actual reshuffles were quite rare.

We asked the two newly elevated women to interview each other, so that TRUE Africa readers could get a sense of their plans and ambitions.

CL: Olivia, African art has for a long time been less recognized than art from other cultures. Why is that in your opinion?

Africa’s symbolic “loss of status” is a phenomenon closely linked to the rise of eurocentrism and imperialism.

It is important to remember that the West was never the center of the world to other cultures, at least not until very recently. To quote Uzodinma Iweala in a recent podcast hosted by my friend Adama Sanneh at the Moleskine Foundation, the West, and other symbolic spaces after it, had to find an “underdog” to positively measure themselves against, and justify to themselves their own preeminence, hence, the right to exploit, dominate, colonize, govern. In French, “La mission civilisatrice”.

The mainstream narrative around the continent has revolved around these definitions ever since. What we do not often realize, because it is so hard to quantify, is the negative material, economic and symbolic impact of these narratives on every area of the continent’s life, be it cultural, political, social, economic.

The lack of recognition for art from the continent is part of that collateral damage. To give an example: patronage is, in most countries, a function of a certain social, political and economic “elite”. A form of social leadership, often hereditary, often linked but not always one with the political, religious or military powers of the day. Look at the Medici for example.

But when a country, a kingdom, a community’s social and political structures face a collapse like colonialism, the families who would be expected to uphold crafts, architecture, and the arts through patronage and through commissions, cannot fulfill that role… Either because they have been wiped out, exiled, or robbed of their power and status. This is what the art ecosystem at large on the continent and in the diaspora is trying to rebuild, painstakingly.

OA: Charlotte, what is in your opinion, the biggest misconception about African art?

While working at Sotheby’s in Paris, back in 2017, I used to organize conferences and roundtables on Contemporary African Art. At the time, I was surprised to discover that most of our collectors, despite their interest in many categories of collecting, were quite ignorant about Africa and its contemporary art scene.

They, indeed, had no idea of what contemporary art coming from the continent looked like. At the very same moment, the Parisian newspapers all asked the question “What is an African artist? Should we talk about African art?”

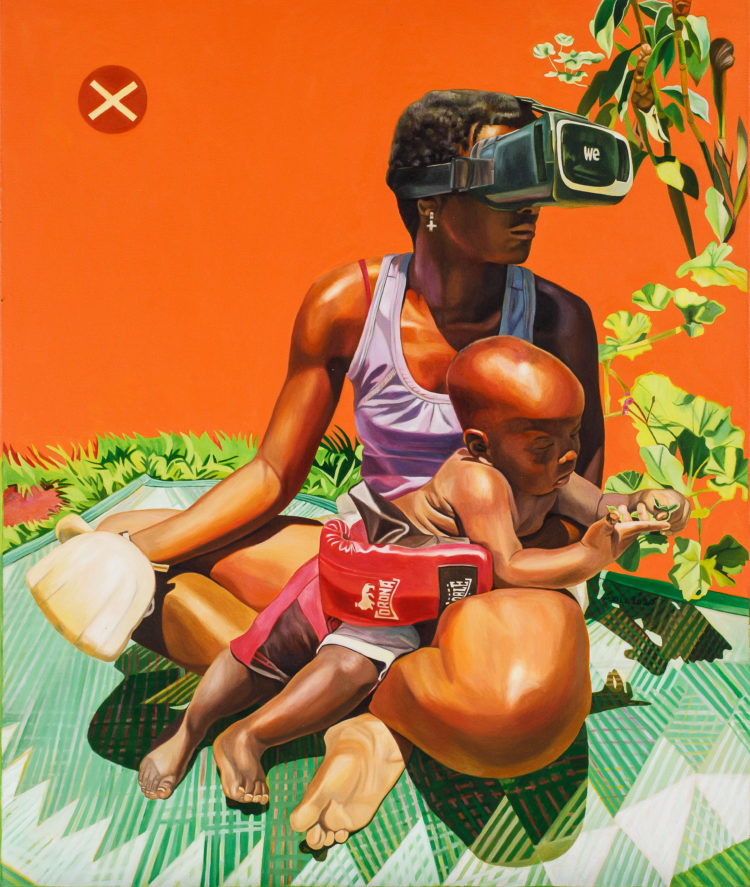

For many years, African art in France has been linked to the art scene presented in 1989 by the curator André Magnin, who has since become an art dealer. The auction organized by Sotheby’s of a selection of works from the Pigozzi collection in 1999 reinforced this perception of African Art in people’s minds: African art had to be colorful, naïve somehow, figurative.

This vision has driven the perception of African art for many years. Worse, some collectors even asked me if African artists continued to produce works in wood (laughs) in the continuity of “traditional” arts.

Fortunately, since then many exhibitions have been held in Paris and elsewhere in Europe, the United States and beyond, bringing a new and more global reading of the African art scene. Museums have set up dedicated departments offering quality propositions. Social networks have also favored the visibility of many African artists and artists from the Diaspora who have all, little by little, gained visibility.

New curators have brought a new reading highlighting the artistic richness of the entire continent. An auction house like Piasa has played its part in the recognition of this market and I am happy to continue and enrich the work started to allow for a more inclusive point of view, involving the global south.

OA: You indeed worked in Classical African Art for many years. What links do you draw between classical and contemporary art from the continent, if you find there are any?

It is interesting to stress that the terminology “Classical African Art” has been used for less than 10 years, and it was initiated by Africans themselves. Sotheby’s has been using it since 2013, in an effort to give a place of choice to the so-called anonymous masters side by side with the most famous contemporary artists of this century.

Knowing about classical art helps me to understand some of the topics and preoccupations raised by African artists in their practice. As a matter of fact, many of them are questioning the “stolen” history of their own country and of the continent.

Artists such as Kader Attia, Pelagie Gbaguidi have both carried out research on the amputation of a collective history through the theft or displacement of so-called traditional objects. The fact that the younger generations do not have access to these objects to construct themselves as individuals, and as a result are missing out on the collective history of a nation, is very damaging, as the artists point out.

Dimitri Fagbohoun and Thierry Oussou respectively question history by working on some emblematic objects. Those that have attained the status of icons on the European art market, through the illustrious collectors to whom they belonged for the former, while the latter patiently reproduces the excavation of the mythical throne of King Ghézo, known in the West as the throne of the King Béhanzin of Abomey.

The exceptional character of this throne rests on its aesthetic qualities, its importance as the regalia of the last independent king of Abomey, its rarity and finally its history. Collected by Colonel Dodds in 1892 and brought back to France in 1894, the royal throne, one of several examples owned by the kings, remained in private hands for many years before being auctioned off in 2004 at a special sale by Sotheby’s, where it was bought for 140 000 €.

OA: What is your most memorable place, trip, or experience on the continent?

My aunt went to live in Algeria and then Tunisia when I was very young and North Africa has always been on my mind. Later, when I was twenty years old, I discovered Côte d’Ivoire during a trip with my best friend, an Ivorian who arrived in France just after her high school graduation.

With her, I traveled the country several times from north to south and from east to west. I discovered the village festivals, the maquis, slept under the stars on the beaches of Assinie and Grand Béréby. This first experience will undoubtedly remain the most memorable to me.

In Benin, the country where my in-laws live, I like to feel the crossbreeding and traditions that are still strongly rooted in the different communities. The vodun is present everywhere and the Fa is regularly consulted. The landscapes, those of Senegal, the Sahel, Mali, or even those of Morocco where I have traveled a lot, always bring me a sort of fulfillment.

More than anything else I remember, from the very small part of Africa that I had the chance to visit, its hospitality and its resourcefulness. When traveling there, I don’t worry about a thing, as everything is possible.

CL: Olivia, on the subject of travel, you speak Mandarin fluently and lived in Asia for several years. What lessons do you draw from your experience in this region?

I developed an interest in Asia very early on. Before traveling there physically, I traveled in my mind. I remember drawing new year’s cards and including a kanji like “Uma” (horse) as early as seven-years-old. It actually all started with a book on Japan, which I borrowed from my brother and returned only ten years later, I think.

That book taught me that Japan was not only anime and video games, but also salarymen and off course, shinto culture strongly rooted in the agricultural society that Japan was before becoming an industrial giant. Later on, I had the chance to travel to Beijing for a one-year language program, which eventually turned into six years.

I believe, and I keep saying this, that the Asian market is a blueprint for what the African art market can and will be, if we do it right. And I believe this to be true not only for modern and contemporary art, but for classical African art as well.

A few decades ago, China was in the same situation as most countries on the continent in regard to its classical art: with the exception of Taiwan, most masterpieces were housed abroad, in western and Japanese private and institutional collections, totally out of reach for the average Chinese citizen. And just like the continent, the scholarship and expertise lied where the works were, abroad. How do you study and maintain the knowledge without the works?

It is easy to blame Africans for not being interested in their own art and cultures, when even without taking into account the issue of funding, even armed with passion, local scholars and art lovers start at a huge disadvantage when compared to scholars abroad.

The main difference in my opinion, is how prompt and reactive Chinese collectors and the general public have been, the minute prosperity knocked on the door. All of a sudden, a Chinese businessman could have access to imperial porcelain… Something that a hundred years before, no amount of money would have been able to buy.

Imagine, after decades of privations and hardship, finally being able to access even a tiny bit of the mystery behind the Forbidden City’s tall walls, and drink tea, like Liu Yiqian, from a porcelain bowl that an emperor, many years before you, may have used personally! A dream.

The Chinese collectors did not think twice, and fast forward today, Hong Kong is the undisputed capital for the market of Classical Chinese Art, most scholars and experts, auction specialists, collectors in this category are Chinese. You should see the rooms in Paris and London during auction season…. One can count the western players on one hand. It really is my dream to see something similar happening with the African market.

CL: You are also interested in African American artists, right?

I am very excited about, and follow closely, the production of African American artists, the institutions and collecting linked to that sphere. For me African American contribution to American culture and to its impact on a global scale is hugely underestimated, and undervalued.

There is no global American cultural hegemony without the African American contribution. We know in Asia for example, the impact of K-pop culture… But K-pop culture is inseparable from its African American references and inspirations. And I love that.

To come back to Asia, what I found there in resonance to my African experience growing up, is something that I like to call “Postcolonial Ballin”. We all have to deal with the West, and the capitalist culture we live in, but we do it by infusing it with our own cultures, from Havana to Abidjan to Seoul, we have our own heroes, our underground, our history and we are having fun with it.

The irreverence of David Hammons is a perfect experiment in Taoist philosophy. In the quiet fury of early performances by Zhang Huan, I see an echo to what Robert Farris Thompson called “coolness as a moral quality” in African Art, a certain dignity and a test of character under the most strenuous of circumstances.

Japanese architects like Tadao Ando and Kengo Kuma are giving shape to shinto philosophy, just like Francis Kéré and David Adjaye do not see the point in creating buildings with no ventilation in warm climates, buildings that cannot survive without air conditioning. Which doesn’t mean they cannot use concrete or technology in telling that story.

In that vein, I love the playfulness of Emo de Medeiros’ electro-fétiches. Julie Mehretu’s most recent record was achieved in Hong Kong, maybe because of the way she explores negative space, arguably the most important concept in classical Chinese painting, as a material in her work. Postcolonial Ballin: that’s the kind of energy I am interested in.

Piasa’s auction of Contemporary African Art will take place on May 19th, at 4pm France time. More information here.