‘I almost get the sense they put the whole conference on just for us.’ Sénamé Koffi Agbodjinou is just home from the 11th annual Fab Festival on the MIT campus in Cambridge, MA. In Paris he runs a registered nonprofit design studio, L’Africaine d’architecture. He splits his time between here and Lomé, the lively, low-lying capital of Togo, that hugs the border with Ghana and the Gulf of Guinea.

His verdict on the conference is optimistic. ‘Really, for the past two years that I’ve attended, this was my instinct: the whole event was planned around our lab.’ The Fab Festival’s theme last year, when it was hosted in Barcelona, was ‘Fab City’. It suggested that the labs – community workshops offering free training and access to a variety of digital creative tools (3D printers, laser cutters, milling machines, etc.) as well as access to a local and international community of ‘makers’ – might begin to take on the challenges of 21st century urbanisation.

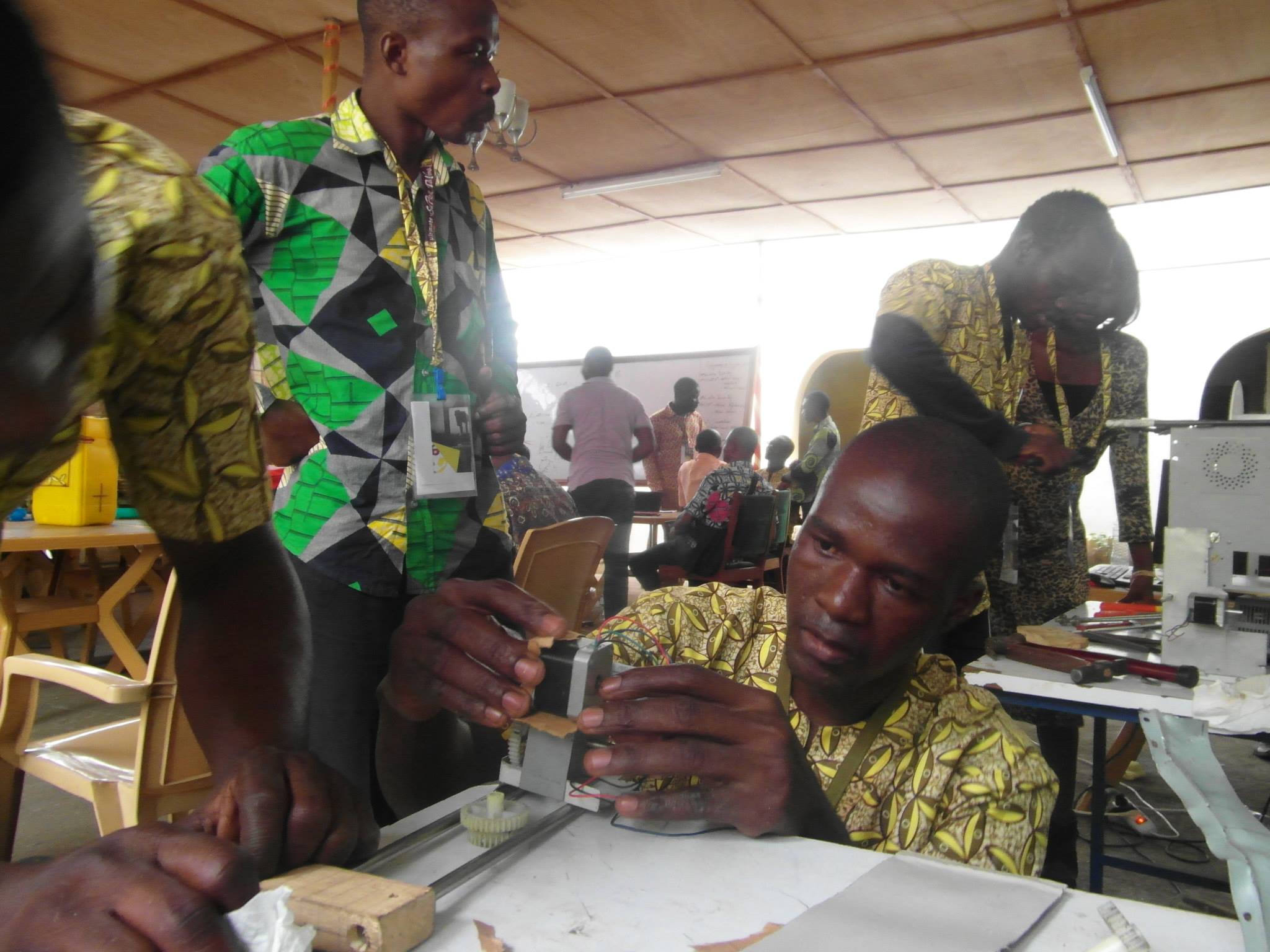

In Lomé, Sénamé runs WoeLab (pronounced ‘weh’ – which means ‘do it’ in Ewe), his Togolese version of a Fab Lab. The space is equipped with a variety of tools, many of them homemade. It offers classes and open sessions to students and young professionals, including a few children for whom the lab is also a shelter.

‘It’s giving people a sense that they can solve their own neighbourhood’s problems, rather than wait for the decision-maker or the urbanist to come and do so.’

WoeLab isn’t a full Fab Lab, properly speaking. It doesn’t have the inventory of equipment required by the MIT-based Fab Foundation, which maintains standards across the international network. But Sénamé’s optimism is spot on and his lab is at the heart of the movement’s experiment in the future of making. At the first Global Fab Awards in 2014, WoeLab won first prize for developing Africa’s first 3D printer made out of recycled parts. ‘Some Fab Labs are places to work on a hobby over the weekend. To make dining room furniture.’ WoeLab’s goals are more ambitious.

As well as an IT social entrepreneur, Sénamé is an anthropologist and an architect. He launched WoeLab in 2012 precisely to take on the challenges of the city. He is fascinated by the idea of vernacular design: in the village the shapes of buildings, the layout of streets and paths and by extension the organisation of village social structures reflect a sophisticated and long-held heritage. That heritage is lost, Sénamé offers regretfully, in the individualism of urban life. No doubt he’s right that a history of local know-how, trampled under the city’s lack of intimacy, might, once recovered, tilt the balance towards higher standards of living.

Perhaps he’s also right that the innovation of ‘makerspaces’ or ‘hackerspaces,’ at a more manageable neighbourhood scale and according to their users’ own needs and creativity, might offer exactly the vernacular know-how that he is trying to recapture. ‘It’s giving people a sense that they can solve their own neighbourhood’s problems, rather than wait for the decision-maker or the urbanist to come and do so,’ he explains. It’s development from the ground up.

The synchronicity between the parent movement and the Togolese Fab Lab is not such a surprise. Entrepreneurialism is part of the national culture in Togo.

From this perspective, the Fab Lab is an incubator for local entrepreneurship and problem solving. WoeLab positions itself as precisely that. Its 3D printer has given rise to two small businesses, producing parts for GPS devices and for small motors. Togo has always been full of ‘makers,’ Sénamé observes, ‘but there is a lack of professionalism in design,’ he adds, which Fab Labs start to address by granting users access to technology, and to one another. Fab Lab-ers can easily make, experiment, replicate, and eventually establish small production lines. ‘They know intimately what customers need and want – this is how a lot of African informal economies already work.’ The ‘mass customisation’ made possible by access to these tools is what Sénamé calls ‘Low High Tech’. It’s a democratisation of technology that he thinks can change the world.

This year, a decade after its founding, the Fab Festival returned to MIT. It was called ‘Making: Impact.’ It was an inquiry ‘into environmental sustainability, conflict resolution and peace building, disaster relief. And the big focus was about creating business out of Fab Labs,’ confirms Anna Waldman-Brown, one of the conference’s organisers. She is a self-described ‘champion of grassroots manufacturing’ who has been especially active in encouraging the West African fab community. Both she and Sénamé say that the impromptu meetings with others in the fab community are these yearly get-togethers’ most valuable moments, where honest learning happens between leaders. Next year’s conference, to be held in Shenzhen, China, will be about ‘Fab Labs making Fab Labs.’ Sénamé is looking forward to it; WoeLab is about to spawn a cousin, so the two spaces can begin to experiment with innovations that are specific to their respective neighbourhoods.

In retrospect, this synchronicity between the parent movement and the Togolese Fab Lab is not such a surprise. Entrepreneurialism is part of the national culture in Togo. ‘Togolese are incredibly resourceful people,’ Sénamé points out. ‘Scarcity often means they don’t have a choice.’ And for the lab’s assortment of users, the stakes are sky-high. Throw in the right tools and the right access to ideas, and homespun creativity can turn into opportunity. That is the spirit of WoeLab’s phenomenal experiment in urban problem solving.