We walk up the stairs of the Palais de la Culture in central Bamako in the dark. The South African writer and curator Riason Naidoo is giving me a private tour of a selection of images from archives of the iconic Pan-African culture magazine Drum. Outside, people are jogging in the thick dusk and a group of children and young adults in brilliant white karate uniforms practice on a dusty floodlit court.

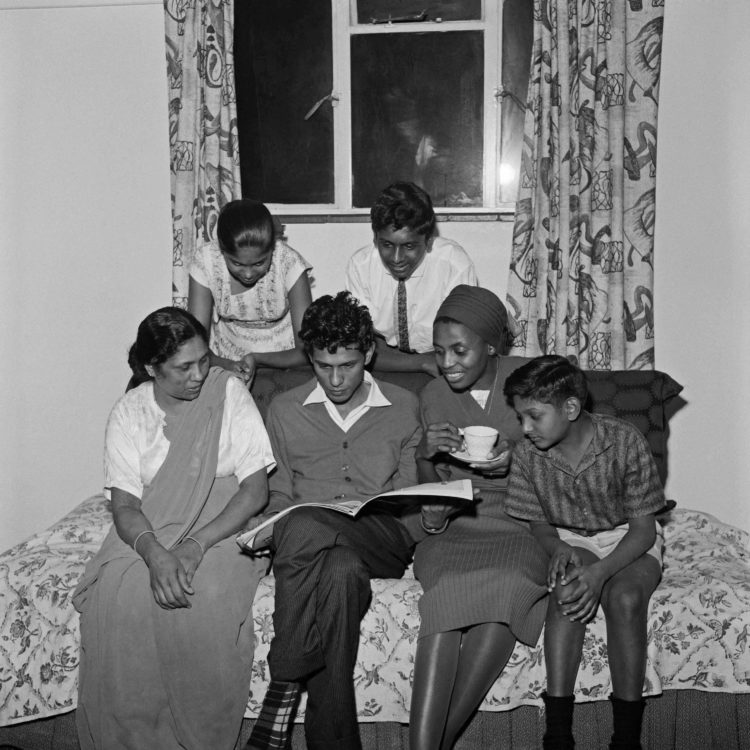

As the guards do not know where the light switch is, Naidoo uses the torch on his mobile phone to illuminate the 18 black and white images of prominent South Africans of Indian heritage: activists, fashion models, sportsmen, daredevils and gangsters. “Papwa” Sewgolum, the black caddy turned three-time winner of the Dutch Open, is captured taking a swing with a golf club. In a photograph taken by Ranjith Kally, an Indian South African photographer, the jazz singer Sonny Pillay sits at home, his mother in a sari on one side, his girlfriend, a young woman called Miriam Makeba, on the other.

It is part of a decade-long project to shine a light on the diversity and creativity of Indian communities who were subject to Apartheid in South Africa in the 1950s. Naidoo has not only delved into Drum‘s archives but entered the houses of Durban’s Indian community to open their family albums, bringing individuals and their daily lives to light.

This is just one moment in Bamako Encounters, the African photography Biennale, which is celebrating a quarter of a century since its founding. While the festival offers an unparalleled opportunity to speak to artists and curators about their work, it also has suffered some teething problems. This year, there is an ambitious new committee in charge and the festival has expanded across 11 venues, not to mention the numerous fringe events. More than 150 artists have been invited to participate, from South Africa to Egypt and to the Diaspora. All this in a national security situation which continues to be precarious.

The country is home to what has been dubbed the UN’s “most dangerous mission.” On 26th November 2019, a few days before the opening, 13 French troops were killed in a helicopter collision. Over 100 local troops have been killed in skirmishes with jihadists in the last few months. Putting on the festival is in itself a political act. During the opening ceremony, the Minister of Culture said the festival was part of a fight against obscurantism and religious extremism. “Photography, quite literally, means to write with light,” she said.

It was the presence of women photographers capturing intimate scenes of everyday life and traditional rituals that felt the most revolutionary.

The Encounters have always been political. When Bisa Silva curated the 2015 edition – which had been cancelled twice before due to political instability – she wrote that even at its inception in 1994, the festival was seen “as an opportunity to test the capacity of culture to rehabilitate the nation’s image and restore international confidence.”

This year marks “a real turning point,” says Astrid Sokona Lepoultier, an independent curator who is part of the curatorial team. The French Institute, which provides financial support, has stepped back from the festival’s organisation. The printing and framing which used to take place in France – the works would be shipped there and back – is now being done by Malian printers and craftsmen.

“It was time; we have the facilities in Mali,” says Lepoultier, “Would you expect any different in what’s known as the African capital of photography?” Most works are pinned with nails or magnets to the boards. At last year’s edition, there was a noticeable absence of Malian photographers. There seems to have been a real effort to include homegrown talent this year.

Photography is political; it is full of choices: from what you decide to photograph to how you decide to photograph it and, of course, who is taking the photograph. It was the presence of women photographers capturing intimate scenes of everyday life and traditional rituals that felt the most revolutionary. Lepoultier says this was due to a concerted “effort” by the artistic director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. “It also seemed important to put forward collectives of women photographers,” she adds.

Over a third of Malian women have experienced gender violence and sexual abuse.

Fatoumata Diabaté is the current president of the Association of Women Photographers of Mali (AFPM), a group of over 20 photographers. Her work is displayed alongside among six other AFPM members and captures ordinary women transfixed and illuminated by the glare of the television, in their homes, their workplaces and on the streets. The images of other photographers show women tying their traditional robes, or on their wedding nights, or in old age.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B6-PdrWgJoK/

Her images are also part of an exhibition made up of six women photographers displayed in the Lycée de Jeunes Filles. The accompanying text discusses the term “sutura”, which is the cultural norm of women staying silent when they are victims of sexual violence in order not to bring shame on their family. According to the United Nations, over a third of Malian women have experienced gender violence and sexual abuse. A recent survey claimed it was the fourth worst place in the world to be a woman. The images are beautiful and varied. Some show women in white wedding dresses, others in ceremonial outfits, others are of young girls who look at the camera defiantly.

Even gathering that number of women photographers is a feat. Diabaté remembers that in one of the first photography classes when she started learning her craft, there were around a hundred women. She thinks she may be the only one still working in photography today. The exhibitions at Bamako Encounters 2019 show that this is changing. “We inspire each other,” Diabaté says. “With time, we’ll finish by getting there.”

Bamako Encounters runs from November 30, 2019 to January 31, 2020. More information here.