Stepping off the plane in Rio de Janeiro I’d have never imagined I’d feel any sense of displacement.

On landing, I immediately had a feeling of warmth. For the first time in my life, I felt and looked like the majority. Over 50 per cent of the population identify as black or mixed-race. In the thick of a Carioca summer’s night, the presence of my extended kinfolk, removed from the bondage of slavery, felt like an embrace.

Brazil has often been erased from conversations regarding racial inequality and oppression. When Rafaela Silva won gold for the Olympic Judo team at this year’s games in Rio, she represented the voices long ignored from Brazil’s favelas.

She manifested a spirit of resilience that has been a characteristic of black Brazilians.

Her triumph is a particularly compelling achievement; she comes from one of the poorest favelas in Cidade de Deus, and who has faced prejudice for being a black woman. ‘They said I was a disgrace. Here I am: an Olympic champion in my home town.’ She manifested a spirit of resilience that has been a characteristic of black Brazilians for centuries.

Anna, a local footwear entrepreneur and housemaid whom I met in the neighbourhood of Glória through a friend, told me that black people in Brazil, use this sense of belonging as a strength. ‘We don’t need anybody to offer us handouts; we’ve earned our right to have these places anyway. We built this country with our blood and sweat.’

Brazil’s hostile climate towards black and indigenous people is difficult to ignore.

Her dream is to inspire others. ‘The way that I define my struggle and equate it to my blackness, is that I want to work hard … so that I can become successful and be an example to others.’

But Brazil’s hostile climate towards black and indigenous people is difficult to ignore. The international community has been shocked by reports in media that many favelas and small communities had been bulldozed over to make way for the Olympic Games. It’s become a story for the socially aware to share on social media but for Brazil’s marginalised communities – mostly made up of black and people of colour – it’s a reality.

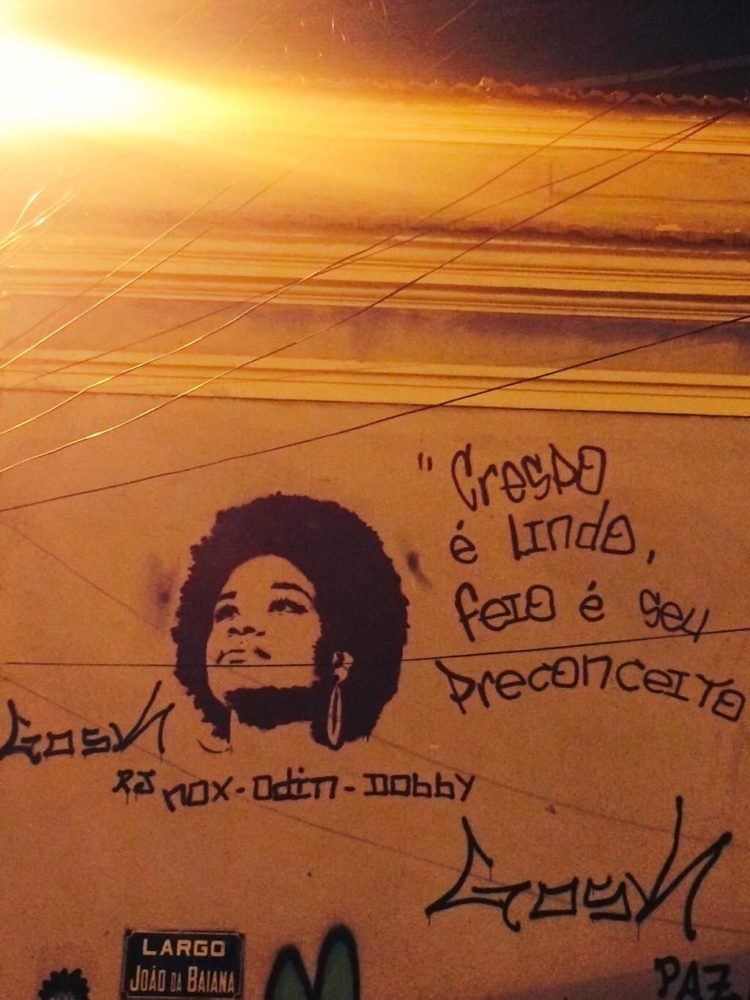

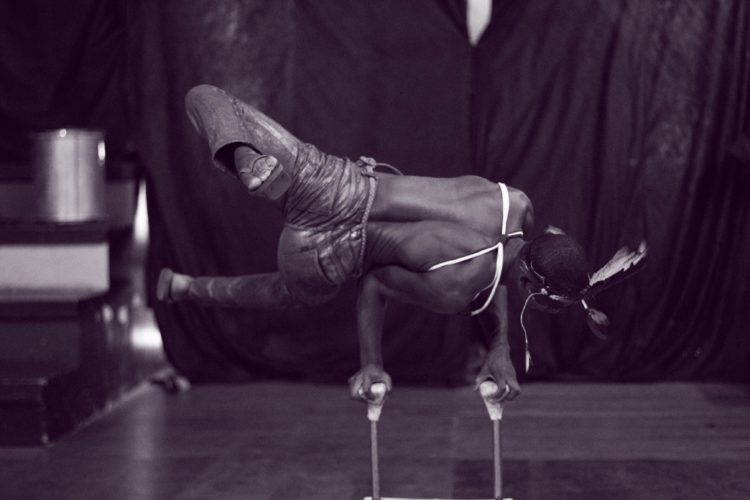

Brazil’s mired history has had a colossal role in how the country’s black community express their identity: they have never shied away from organising, whether in secret or in public. It’s said one of the earliest forms of Capoeira, the Brazilian martial art originating in Angola, was adapted to suit the conditions of colonial Brazil and served as a form of defence for escaped slaves. It is also why Afropunk, an anti-establishment DIY scene which centres the voices of marginalised black people, is growing in popularity in Brazil.

Rio de Janeiro’s DIY-samba street parties in Pedra do Sal are developing their own iteration of Afropunk, suited to Carioca’s atmosphere.

Carioca was initially an area where escaped and freed Bahian slaves would find refuge. The Quilombos, a group of African resistance fighters who provided refuge to any slaves who considered themselves free, eventually built a community that became a centre of blackness in Rio. The small neighbourhood is often called ‘Little Africa’.

To some, Pedra do Sal is hallowed ground, a stark reminder that black people of all creeds can find sanctuary among other free people. It’s the kind of environment where black music can thrive naturally and live in harmony with the surroundings.

Every samba party held to this day is a continuation of the free and expressive culture that has existed in the area since Aunt Ciata, widely regarded as the mother of samba, first ignited the genre. The energy in that small enclave, almost completely removed from the daytime hustle of downtown Rio, is overwhelming.

Artists come along to perform and reflect the times through their music. Afropunk band Project Black Pantera, whose name refers to the radical black empowerment movement the Black Panther Party, is made up of Rodrigo Augusto and the brothers Charles and Chaene Gama. Project Black Pantera are unabashed in their heavy metal sound and addressing the issues that plight Brazil.

Amnesty International have said that Brazil’s military police have been responsible for more than 1,500 deaths in the city of Rio de Janeiro from 2010 to 2015. And between the years of 2010-2013, 79 per cent of these victims were black. The presence of Project Black Pantera in a nation where the majority of the population happen to be the most marginalised is rousing.

Afropunk exists as an abrasive, alternative sound.

Like TCIYF in Soweto, Project Black Pantera blend elements of thrash metal with hardcore punk to communicate the experiences of black people to the world. Then there are the likes of Aláfia who represent a more traditional, Yoruba-inspired funk sound. They incorporate the drums of the religion Candomblé. The symbolism is strong; drums have long had a significant role to play in resistance in the history of West Africa and Brazil.

Some argue that constant erasure in media and reality means black music is intrinsically punk. Of course, there are commercial black artists who rarely address socio-political issues. But Afropunk serves to remind us that black music is a rich source of protest that the diaspora seeks to preserve and develop for generations to come.

Afropunk exists as an abrasive, alternative sound, which gives space to black rock artists who find themselves left out of wider rock and punk conversations. It speaks of the diaspora’s experience with institutional racism in a continually changing manner.

A punk attitude must be a daily ritual.

Through interactions with black Brazilians, it’s also clear that to survive and thrive in the nation they have built, a punk attitude must be a daily ritual, a natural characteristic perhaps.