New-Orleans native Shantrelle Lewis has spent her 10-year career as a curator researching Africa and the diaspora and uncovering questions around identity.

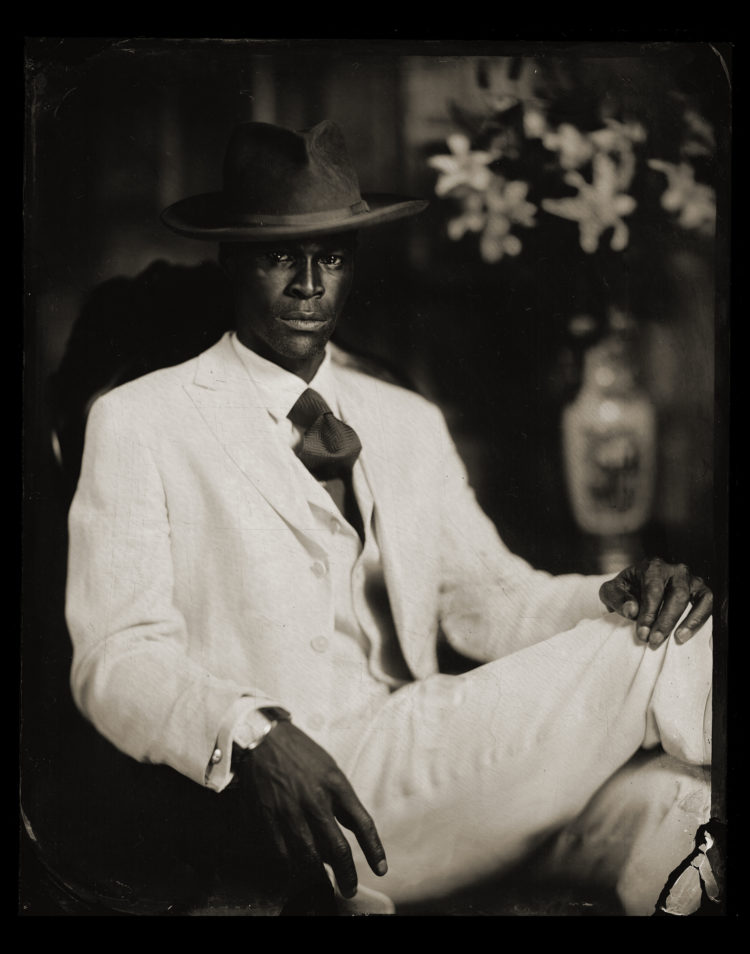

Her exhibition Dandy Lion: (Re)Articulating Black Masculine Identity, currently on display at San Francisco’s Museum of the African Diaspora, features images of black dandies from across the globe.

Now in its sixth year and approaching its upcoming UK premiere in Brighton this fall, Dandy Lion presents a narrative of the urban black man that seeks to challenge the stereotypical and monolithic image of the ‘black thug’.

It invites us to consider the diversity, intricacy and layers that constitute the identity of the cis-gender black male and speak to the Afropolitan nature increasingly found in Africans who identify with multiple nationalities and cultures.

We sat down with curator Shantrelle Lewis for her thoughts on Dandy Lion, dandyism and black men in the 21st century.

What inspired you to create the Dandy Lion project?

My work has always been grounded in research on the African diaspora, with a focus on the aesthetics and origins of people of African descent. Questions around identity inform my portfolio projects. I look for untold stories and unexplored narratives because we’re so saturated today with the same, limiting narrative about the black experience.

Dandy Lions themselves represent a plethora of nationalities and regions.

This topic wasn’t as hot when I started as it is now, but I explored it in response to the hyper-thug narratives of black men that were being portrayed in media. I wanted to address very direct narratives of how black men self-identify, which is juxtaposed to other stories of who they are as people.

I first curated Dandy Lion in 2010 at a pop-up gallery space in Harlem for Society HAE. The photographers of the exhibit, who represent an international cohort of both emerging and renowned artists, selected their subjects. Both the locals and the Dandy Lions themselves represent a plethora of nationalities and regions – Johannesburg, Brazzaville, London, Amsterdam, Brooklyn and Chicago.

What is the core message you want visitors to walk away with when they view Dandy Lion?

I want people to walk away realising that black people are not monolithic. The African diaspora is vast. There are millions of untold stories. From black debutantes in the US south to, for instance, my uncle who was an Olympian track runner – there are so many beyond the current image being portrayed, and black dandyism is only one. There isn’t one African-American narrative, nor is there one continental African. Our experiences, our identities are as nuanced and as complex as any other group of people.

I feel like with this exhibit, there is a point of entry for everyone, despite gender, race or sexuality. Everyone can find an element in one of the portraits that they can identify with.

The exhibit notes the conscious decision these men make to ‘defy societal expectations’, calling this an ‘exuberant act of agency and defiance in the face of a world that isn’t always friendly to black men and boys.’

In light of recent events in the US and the growing Black Lives Matter movement, why do you feel it’s important to tell this particular story?

What’s happening now isn’t a new problem. Black men have been getting murdered by the police in this country for a long time. This is related to the predominant images we have of black men as hostile and threatening, which have been told over and over and over through media and the news. When I curated this exhibition six years ago, there were black men shot by police in the news then too. We just honoured the 15th anniversary of the death of Prince Jones Jr. who was murdered at Howard University while I was in school there. The list is endless.

I don’t think a suit and bowtie can stop someone from being frisked.

Today you always see particular images of black men – mug shots and photos of men who have been shot – all over the news. Instead we need to show a different picture. This is important for the psyche of everyone, white and black.

While I don’t think a suit and bowtie can stop someone from being frisked or stopped or shot by the police, we can change the dominant narrative about black men and break the link between black man and criminal. If they weren’t constantly portrayed as a threat, the police wouldn’t be threatened by them. We have prevailing white supremacist views of what black men are that need to be changed.

Can the way black men dress have a real impact on these views?

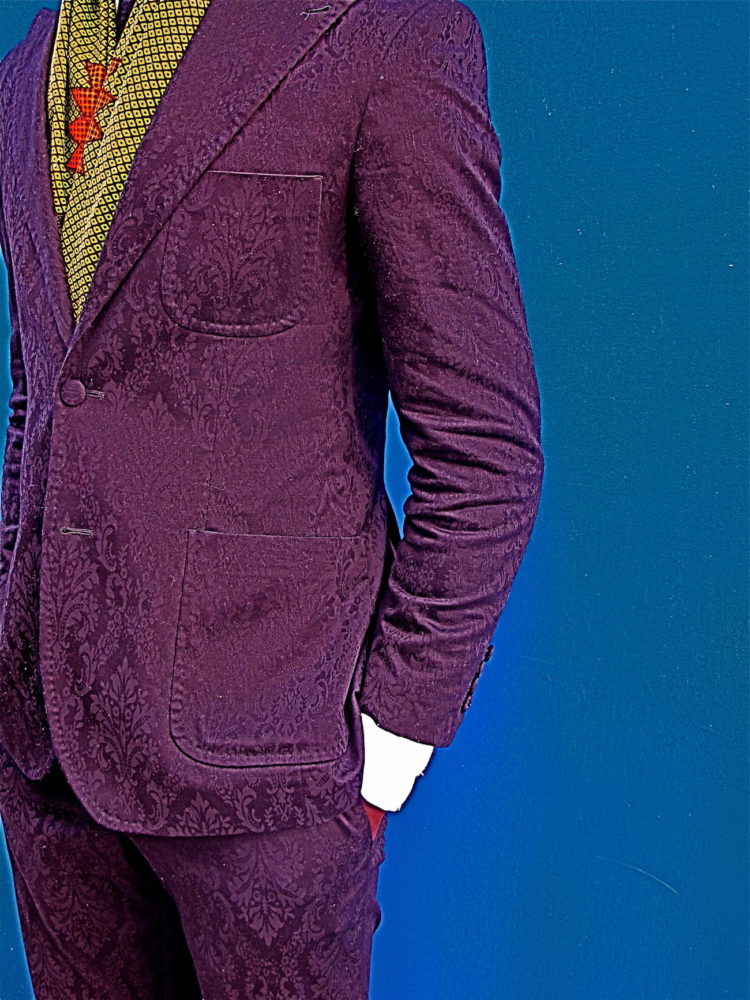

Dandyism allows black men to change how they want to be seen and to express themselves. Dressing up is always part of who we are as black people. For many of these men, though, dressing up isn’t a response to racism or white supremacy or stereotypical images but of the self-pleasure and gratification that comes from adorning themselves in a certain type of way.

Whatever you wear, people are going to judge you anyway. The dandy style is only accessible as armour to a certain extent. If the idea that black men don’t matter and are seen as a threat isn’t wiped out across the board, it won’t make that much of a difference.

Where did this existing narrative come from?

Part of it is linked to the commercialisation of hip hop by mainstream corporate entities. As hip hop grew within the black environment and grew to influence global culture, there were multiple genres of hip hop and clothing and dress that accompanied that. The styles and genres ranged from A Tribe Called Quest to Public Enemy and Run DMC in between.

Then after the release of the Chronic album, the gangster rap and the thug narrative that accompanied it, became the dominant identity of hip-hop culture. This also coincided with Ronald Regan’s War on Drugs and the crack epidemic within the black community. White tees, baggy pants and athletic wear became the dominant uniform. Hip hop then spoke to a specific narrative, and that was perpetuated in the media and eventually hyper-escalated by the Prison Industrial Complex and police culture. The profile of a criminal spoke to that specific type of dress, even though there are some criminals who wear suits and ties and work in corporate America. But the hyper narrative of what a criminal is became synonymous with a hyper-masculine black person.

The other part [of what constitutes the persona expressed though both dandyism and other hip-hop styles] is swagger. It’s an attitude, a level of self-confidence, a cadence in their walk, how they carry themselves. It’s the performance of one’s regality. This predates European influence on men’s fashion in the diaspora. It is inherently African.

This comes from traditional African culture and can be seen throughout the continent or black communities globally. It’s something that goes beyond the clothes they have on their bodies. Dandyism affords black men the space to accentuate this confidence that’s within them, with or without the suits.

Where does black dandyism fit within the hip-hop narrative?

I think it’s not different from hip hop; it’s part of hip hop. Jidenna is recently framing what a black dandy is, Andre 3000 – there are multiple examples of men in hip hop who are looking to a specific type of dress that is different from that predominant image of baggy pants and white tees. This speaks to the diversity of hip hop and the culture.

Historical dandyism is often described as ‘metro-sexual’ or perhaps ‘queer’, as it emulates a traditionally feminine focus on grooming and appearance. Do you perceive modern dandyism in the same way?

Our understanding of gender has evolved. I see dandyism as a queer persona – not in terms of sexual preference – but as an alternative and oppositional identity. Dandies exist on the fringes. Adornment is traditionally seen as a feminine ritual – but Dandy Lions will spend hours grooming, making sure they match and have all the right accessories, a ritual which transcends gender.

Traditional African ontological concepts of masculine and feminine have always been fluid.

Despite the heteronormative and patriarchal society we live in, historically African societies were not so rigid with regard to gender. So much of what we’ve adopted as inherently masculine or feminine is actually Eurocentric. Traditional African ontological concepts of masculine and feminine have always been fluid, never all one thing or the other. So black dandyism, in essence, is a contemporary and Afro-Western reflection of that state of being.

Quoting a muse from James Maiki and Sara Shamsavari’s digital video displayed in Dandy Lion, today’s dandy style is ‘an amalgamation of so many different influences… There’s the traditional elements of African style. But there’s a bit of street and hip hop in there as well.’

Today’s dandies tend to incorporate more traditional African style than in the past, mixed in with the European aesthetic. What do you think is the reason for this?

If you look at WEB Du Bois in the early 20th century, he was pushing dandyism then. But because respectability was so critical for survival, that dandyism didn’t include a returning to traditional African style of dress.

When Europe colonised the continent, it pushed a racist agenda that taught that anything traditionally African was backwards and uncivilised. Now there’s a higher level of consciousness about the culture and traditions we were practicing in Africa before Europeans dominated or colonised African societies.

Black dandies are actually Africanising European menswear.

Historically, all cultures have borrowed and appropriated others. I believe black dandies are actually Africanising European menswear. Ozwald Boateng is the perfect example of the kind of exquisite clash that occurs when African aesthetics meet European fashion.

It speaks to the duality and identity of people as well. You have black men born and raised in London who are of Ghanaian or Nigerian descent, but they’re as much British as they are African. The incorporation of African styles in a dandy framework speaks to the layers that exist within people. Identity also isn’t monolithic.

There are some images in the exhibit that feature dandies, juxtaposed above images of men in ordinary dress at home. Can you speak to what that signifies and why you chose to display it that way?

In the case of the sapeur in the Congo and other regions on the continent, dandyism is a performative expression of nobility despite the economically dire conditions in which they may live. These photographs taken by Caroline Kaminju, gives us access to see the man behind the suit, in his totality, and not just the presentation of who he becomes when adorns himself in expensive menswear. I believe those images also serve to critique the state of many post-colonial societies in Africa – those in which the only form of escapism for some is through the almost deification of couture.

The exhibit describes fashion as a force that can ‘disrupt convention and advance change.’ How can fashion act as a catalyst or inspiration?

Oppositional fashion has consistently been used to shift how specific groups are seen. Iconic images of Angela Davis’s Afro, black-leather-clad Panther Party during the Black Power Movement, for instance, were highly influential on my generation. While most of us don’t dress that way today, just the images and visuals spoke to a resistance against mainstream society. It confronted more respectable images that came out of the Civil Rights Movement where many leaders did anything in their power to assimilate to mainstream society.

When people are literally disrupting the status quo in a visual way – when I’m wear my hair naturally – this disrupts the idea of who a curator is or what a professional black woman looks like.

According to dominant culture, my hair should be straight and I should dress conservatively to work in a museum. Anytime I or anyone else does anything outside of the norm, it’s in direct opposition on the limit.

How does the concept of dandyism apply to black women?

Look at Rekia Boyd, Sandra Bland – black women are also killed by police, and they’re often seen as just as threatening as black men.

There are a few like Janelle Monae – women who are black dandies.

There isn’t necessary a stereotypical style associated with them though which is different, unlike the Dandy Lion. There are a few like Janelle Monae – women who are black dandies and have this style and this culture.

Who are your personal style icons?

I love Tracee Ellis Ross and Solange Knowles. I love anything and everything they wear, how they play with color and structure. Their style is the intersection of what’s sexy, fun, whimsical and modern. Just oh so fly!

Dandy Lion: (Re)Articulating Black Masculine Identity is currently on display in the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco and runs through September 18, 2016. It will be premiering in the UK in October and opens in Miami, FL, at the Lowe Museum of Art in January. A book featuring images from Dandy Lion will be published by Aperture in Spring 2017. More information can be found on Facebook at The Dandy Lion Project.