In this age of Covid-19 devastation, so many lives have been lost that sometimes we forget to pay tribute to the greats. Henri Vergon was one of those greats. The Belgian-born French art dealer died on May 15th, 2020. He was one of the continent’s most beloved champions of contemporary African art. From his base in Johannesburg’s Newtown neighborhood, he ran the Afronova gallery for more than 15 years, with his partner Emilie Démon as his trusted consigliere.

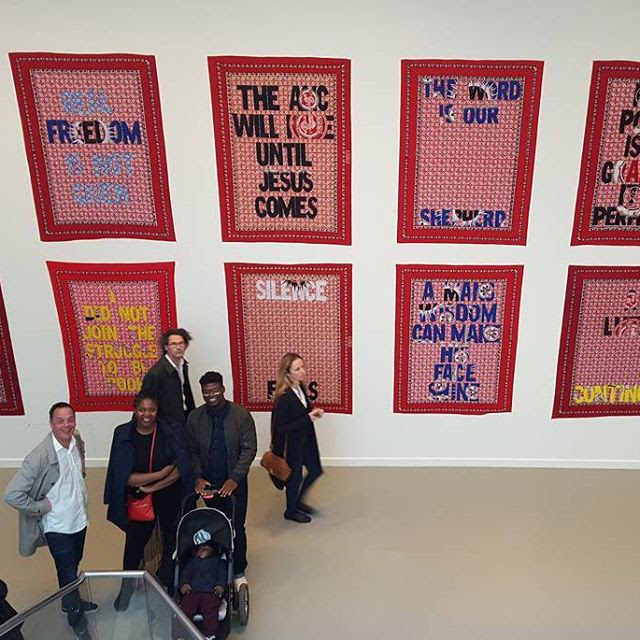

Many art world insiders knew him for his dedication to artists from the African continent and diaspora, and the Afronova gallery stated its mission as aiming “to actively contribute to the intellectual discourse and the emergence of new vernacular art forms from the most urban and contemporary environment on the continent.” Some critics expressed interest in his work with artists Ricardo Rangel and Gerard Sekoto, but I was personally in awe of the way he nurtured younger South Africans artists, including Phumzile Khanyile and Lawrence Lemaoana, a personal favorite I was able to interview in May 2018, at the 1-54 Art Fair in Brooklyn.

I first met Henri two decades ago, when I brought my TRACE Magazine editorial team to Joburg, for a special issue we were producing on the “new” South Africa. At that time, he was working at the French Institute, and he went out of his way to school us on the new dynamics in the post-apartheid nation. We chatted for hours, we partied late into the night, and he introduced us to some of the rising stars he’d identified on the local art scene.

Those who knew him spoke often about his generosity and enthusiasm, which he brought to all his endeavors and personal relationships. I wasn’t surprised when I learnt, less than five years after our first meeting, that he chose to open his Afronova gallery right across from the Market Theatre, which in the 1970s was known as the ‘Theater of Struggle” where black, white and so-called “colored” South Africans would collaborate on mission-driven productions.

On July 3rd, the art consultant Josette Sayers attended a church service around his funeral in Argenteuil, a working-class city in the northwestern suburbs of Paris where Henri’s family is based. Josette sent me an email that day, expressing that Henri’s mother was devastated by the abrupt loss of her youngest son and wanted very much for him to be buried near the Vergon family.

“It is certainly true that seeing a casket speaks of an irrefutable fact,” Josette wrote me. “It tells you a special person has crossed to the other side, no matter how unacceptable it feels. Yes, Henri is indeed gone. The world changes, life goes on, yet bonds are sealed and some are meant to be kept, like the love and friendships Henri nourished with so many people in different parts of the world. So, no, Henri is not forgotten.”