As the curtains draw to a close on Alioune Diagne’s first U.S. solo exhibition at Templon New York on May 1st, the impact of this moment continues to resonate. Hot on the heels of his critically acclaimed Senegalese Pavilion at the 60th Venice Biennale, Diagne’s New York debut marks a powerful expansion of his artistic dialogue—one that has already made waves in Europe and Africa. It is now reaching American audiences with urgency and poetic clarity.

Titled “Jokkoo”, a Wolof word meaning “connection” or “link,” the exhibition is not just a celebration of a rising star in contemporary African art—it’s an intentional act of cultural bridge-building between two worlds that have long influenced each other: continental Africa and the African diaspora in America.

It’s a shared dreamscape, from Senegal to America. “I think there can be an African dream just as America has an American dream,” Diagne asserts—a statement that encapsulates the philosophical core of his practice. This isn’t simply a rhetorical flourish. For Diagne, born in Matam and trained in Dakar and France, the dream is both metaphor and mirror. His canvases explore the long shadow cast by colonialism and the ever-evolving identity of Black communities navigating the global stage.

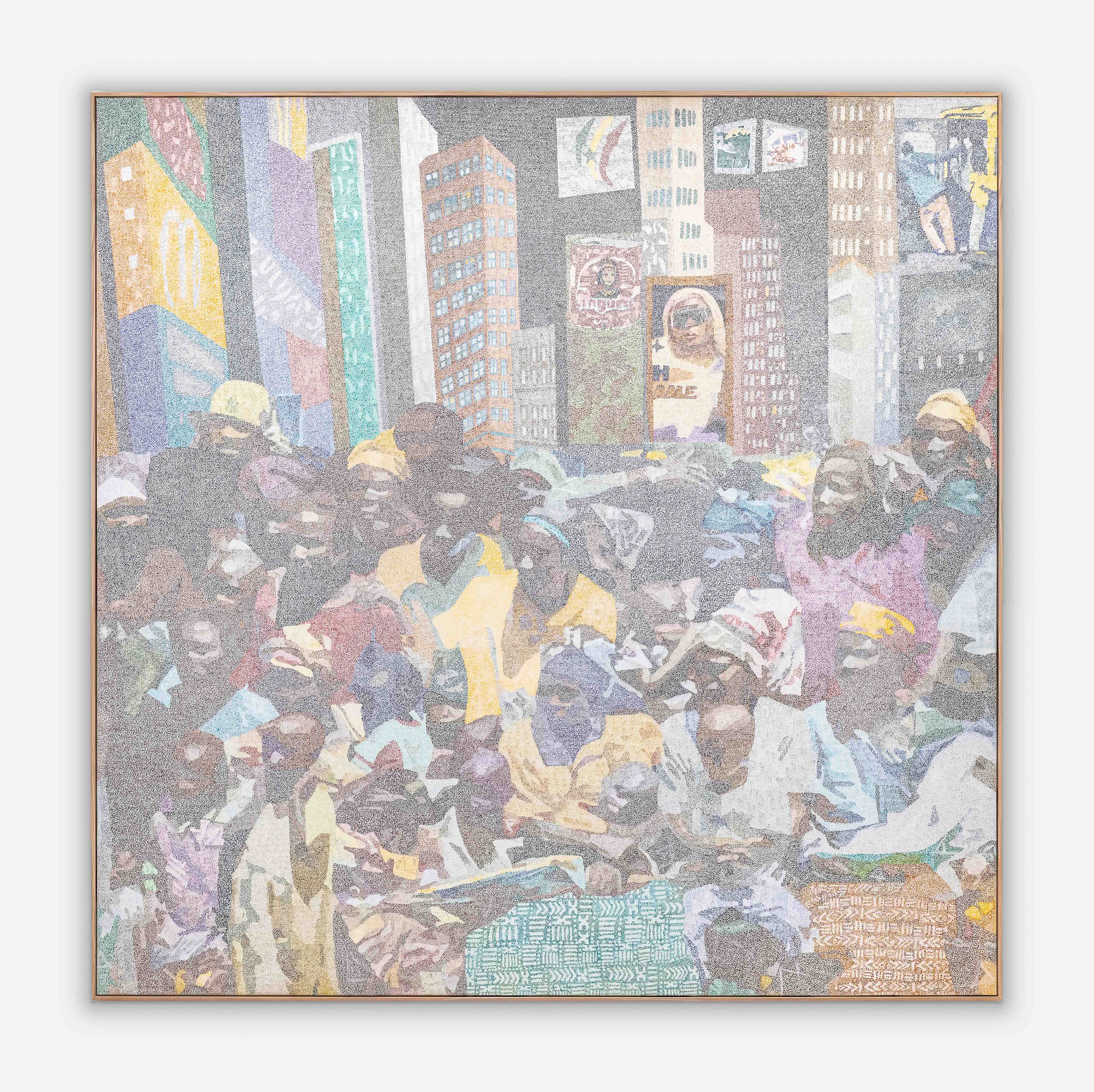

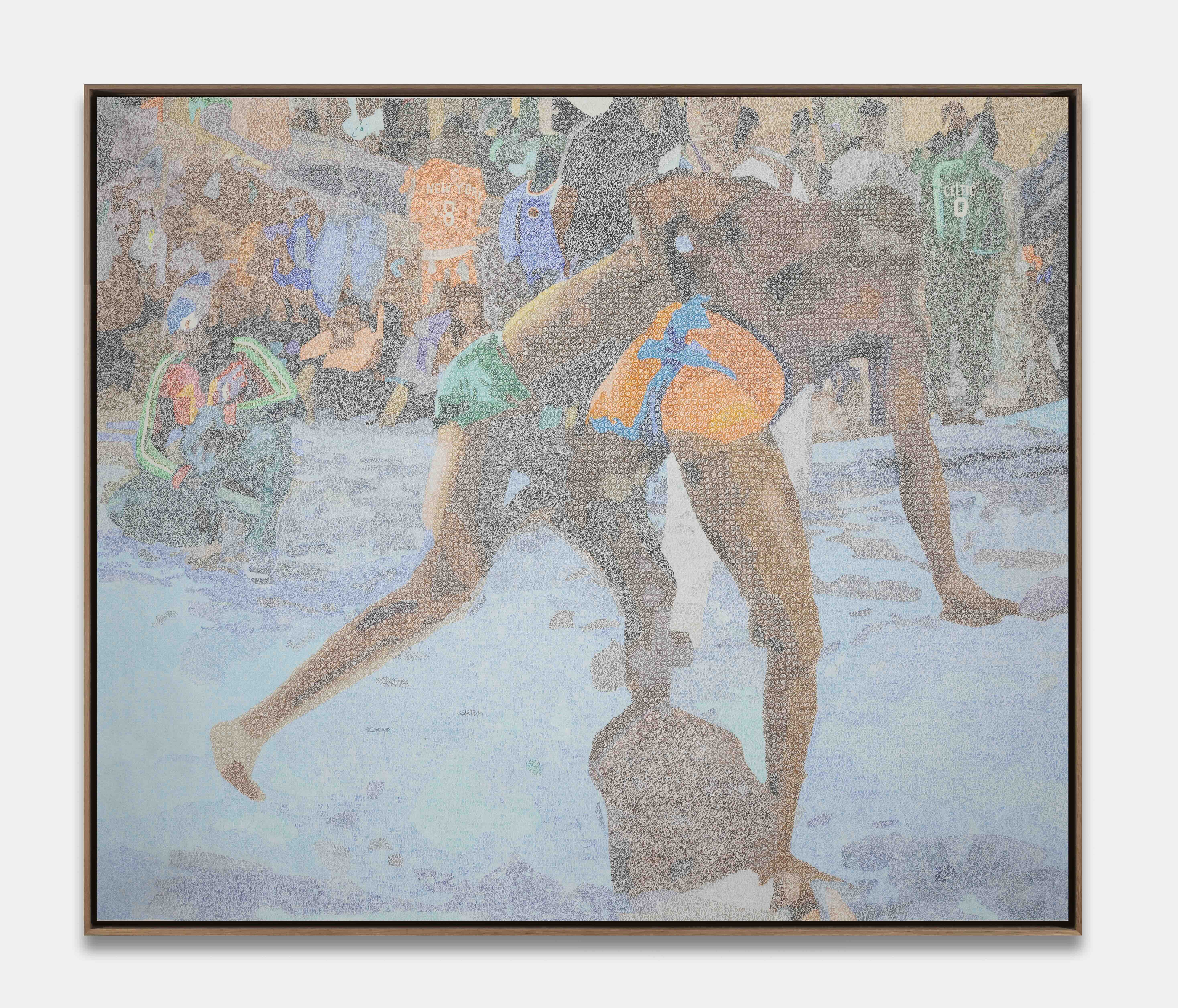

His intricate, pastel-hued paintings are composed of thousands of calligraphic symbols, forming complex, layered figurative scenes. At first glance abstract, the works slowly reveal forms, gestures, and stories. On a tour given by gallerist Mathieu Templon, this viewer was able to spot African American basketball players rise like icons from his surfaces, symbolizing not just sport, but the full weight of the American dream—success, freedom, and self-determination.

“The younger generations in Africa no longer envisage a career on their continent,” Diagne notes. “Their sights are set on the success of the Afro-American community in cultural fields such as sports and music.” Yet despite the news focus on Senegalese boats capsizing in the Mediterranean, his message is not one of cultural escape but of reciprocity and reclamation. “I want to show them that there is a future for them on the African continent. They need to believe and invest in their countries.”

In Jokkoo, which is really a tale of two cities, Diagne draws deliberate parallels between Dakar and New York City, collapsing their visual codes and geographies into one shared canvas; it’s a commentary on both metropolises. “Thanks to my Jokkoo exhibition, I had the opportunity to return to New York and immerse myself even further in the city’s effervescence,” Diagne explains. “In several of the works in the exhibition, I have deliberately blurred the visual boundaries so that the viewer no longer knows exactly whether they are in Dakar or New York, in order to highlight the similarities between these cities.”

“These two cities have much more in common than you might think,” he added in an email interview. “They are filled with a particular energy, with people constantly on the move, with busy and noisy crossroads and meeting points that concentrate people and activities. Both New York and Dakar are places where anything seems possible, full of professional, artistic and sporting opportunities. This aspect is at the heart of the Jokkoo exhibition, in which I have chosen to highlight urban sporting practices such as basketball in New York and Senegalese wrestling in Dakar, two very popular sports that are an integral part of the identity of each of these cities.”

This is more than a visual conceit—it’s a commentary on transatlantic kinship, on the cultural and spiritual currents that flow between Black communities in the diaspora and on the continent. In a series of paintings where basketball courts morph into Senegalese wrestling arenas, Diagne challenges viewers to reconsider the borders of identity and the layers of influence that shape both daily life and aspirational dreams.

With his pan-African identity in motion, Diagne’s work resonates deeply in the context of contemporary conversations around Black identity, diaspora, and solidarity. His references to Black Lives Matter protests and to wrestling—a sport with deep roots both in Africa and in American collegiate culture—underscore the ways that Black cultural expression becomes a site of both resistance and communion.

By tracing these connections, Diagne participates in what could be called a pan-African futurism—a movement that envisions new trajectories of self-definition, agency, and possibility for African and Afro-descendant communities worldwide. His calligraphic method—equal parts visual rhythm and narrative thread—echoes the complexity of these shared struggles and dreams.

It’s a vision beyond borders.

Diagne’s American debut is not just the arrival of a major new voice on U.S. soil—it’s the continuation of a much older conversation, one rooted in shared memory, mutual influence, and a profound desire for cultural and spiritual reconnection. In Diagne’s hands, art becomes a medium through which Dakar and New York no longer feel oceans apart. Instead, they become kindred cities—both flawed and vibrant, scarred and resilient, but filled with individuals dreaming of something greater. Whether that dream is African, American, or something entirely new, Alioune Diagne’s work dares us to believe in it.

Alioune Diagne’s “Jokkoo” is on view at Templon New York through May 1, 2025.