The TRUE AFRICA 100 is our list of innovators, opinion-formers, game-changers, pioneers, dreamers and mavericks who we feel are shaping the Africa of today.

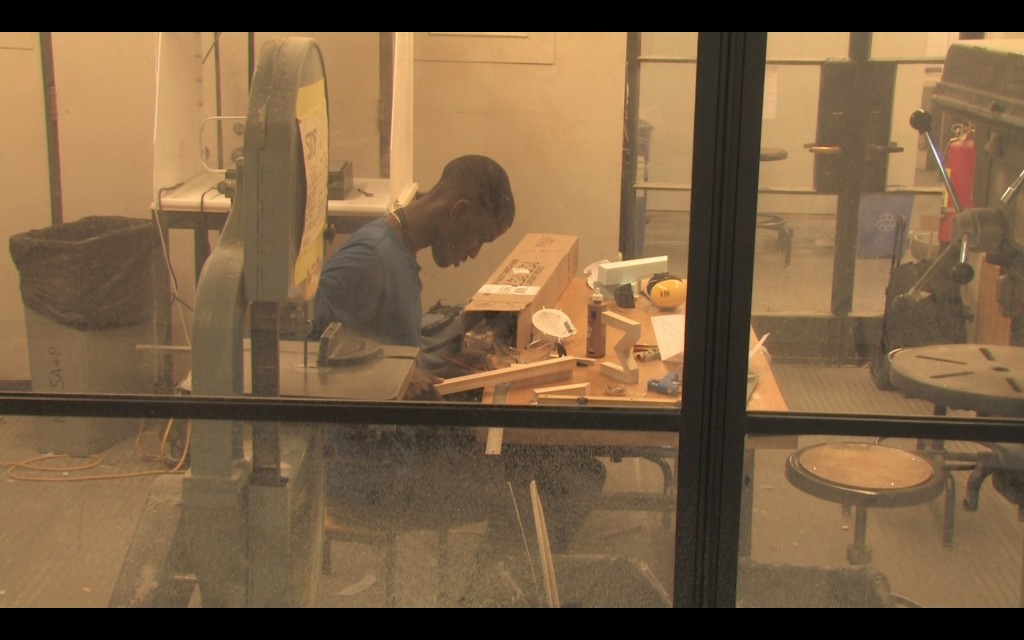

Arthur Musah is a documentary maker with an unusual path. After high school in Ghana, he studied electrical engineering and computer science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Arthur then worked as an engineer for four years but eventually decided to join the graduate film production program at USC’s School Of Cinematic Arts. He’s currently working on One Day I Too Go Fly, a documentary that follows four African students who also left Africa to study in the USA.

Where do you think African cinema is heading?

Tough question. I don’t know. I can tell you where I hope it is headed. I hope African cinema is headed for a boom. I hope African cinema is becoming cinema, moving beyond a niche form for localised audiences and becoming cinema that speaks to the universal while being specific.

I hope that African cinema is headed in a direction that moves our societies to examine themselves critically.

It is exciting to see more Africans making films at home, in the diaspora, and sometimes both at home and abroad. That mixing of influences, ideas and voices leads to reinvention. There seems to be an increasing number and diversity of film festivals on the continent too, which is great because production and consumption have to be developed in tandem.

I also hope that African cinema is headed in a direction that moves our societies to examine themselves critically and to embrace constructive change.

Many of your films relate to Africans living abroad. What draws you to these stories?

Our interconnected world and my own life experiences draw me to these stories. I was born in Ukraine, grew up in Ghana, and now live in the United States.

It is an increasingly common African experience to be from multiple places.

All of those countries, their cultures and their politics have shaped who I am. Many of the people I have met in life have also been shaped by multiple places. In film, I try to create stories that explore who we are, who I am, so I find myself working with characters who are caught between worlds.

It’s not everyone’s experience, but I think it is an increasingly common African experience, to be from multiple places, and the tension of being able to adapt to many places but to never fully belong to any of them is something that I am currently interested in trying to capture. As far as why my films focus on Africans, that’s because I love movies and I simply have not seen enough African lives explored in cinema in ways that have left me breathless.

Who’s your African of the year?

Mrs C.S. Akyeampong, a dynamic playwright and my drama club teacher during my years in the Presbyterian Boys Secondary School in Ghana. She has actually been my African of two decades, because of her influence on my life and the lives of many talented young Africans. I have two illustrative anecdotes about her.

Mrs Akyeampong stood up to him and defended my writing, and that was an important signal to me that my odd interest in writing was valid.

In my first year in secondary school, a teacher failed to show up to teach my class of boys concentrating in science studies. Boys being boys, we just got louder and rowdier as the free period progressed. We were on the second floor, and Mrs Akyeampong left the arts class she had been teaching a level below and walked into our classroom. A hush fell over us and she proceeded to give us the strangest lecture our class of science students had ever encountered: Shakespeare’s Hamlet. We were entranced. To this day, many of us can still quote a line or two from that play because of that lecture. She was that incredible a teacher.

A couple of years later, I had joined the drama club and she had become my mentor. She would stay many unpaid hours on campus reviewing plays, poems and short stories her students had written. We were discussing one of my stories one afternoon when my chemistry teacher walked in and derided my wasting time on silly fictions instead of preparing for my science national final exams. Mrs Akyeampong stood up to him and defended my writing, and that was an important signal to me that my odd interest in writing was valid.

4 years to get to this. Congratulations Sante, Fidelis, Billy, Philip & #ClassOf2015! Keep flying to greater heights! pic.twitter.com/nZ1FKFXRdd

— One Day I Too Go Fly Inc. (@onedayitoogofly) June 5, 2015

Similarly, she nurtured the early talents and curiosities of the likes of Paa Kwesi Imbeah, whose Kasahorow project is working to preserve African languages through technology; Bernard Akoi Jackson (see here), a dynamic contemporary Ghanaian artist working in all manner of media and performance; and Tawiah Ben-Eben M’carthy, an actor and playwright working in Canada; among many others.

Often, our societies celebrate the rock stars, laud those whose work is loud and hard to miss. But there are many other people whose work is momentous even if it is quiet. Many teachers do some of that quiet, important work, and Mrs Akyeampong is one of the most extraordinary ones. Her impact on society is magnified through the lives of the many students she mentored.

Find out more about onedayitoogofly.com

Come back tomorrow for the next TRUE Africa 100 and keep up to date using the hashtag #TRUEAfrica