Curated by Ekow Eshun, Ghanaian-American artist Rita Mawuena Benissan’s 2023 exhibition In the World not of the World at Gallery 1957 in Accra served as a groundbreaking exploration of Ghanaian identity and cultural heritage, melding traditional artistry with contemporary techniques. The exhibition was notable for its reinterpretation of customary Ghanaian symbols, particularly the royal umbrella, a significant emblem of chieftaincy, in use since at least the 17th century. Through her collaborative efforts with local artisans, including royal embroiderers and bamboo carvers, Benissan breathes new life into traditional craftsmanship while addressing themes of leadership, community, and femininity within Ghanaian society.

Among the standout pieces were two monumental Kyiniye state umbrellas, intricately embroidered with historical imagery, and a striking golden throne symbolizing the essence of leadership and legacy. Benissan’s signature embroideries further delve into the spiritual and communal narratives that define Ghanaian culture, particularly some ancient forms of matriarchy, underscored by the adage “Ɔbaa na ɔwo ɔhene” which emphasizes the vital role of women in traditional governance. An 18-minute documentary, which was screened during Accra’s Cultural Week in October 2024, gives further context on the work. It offers an in-depth look into Benissan’s upbringing, artistic journey, and research practice, as well as her project In the World not of the World.

Building on the success of her Accra exhibition, Benissan followed up with One Must Be Seated, a 2024 show that runs until October 2025 at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa (Zeitz MOCAA) in Cape Town. Through tapestry, sculpture, photography, and video, Benissan once again highlights and celebrates Ghana’s rich traditions, this time with a focus on Asante customs. As the royal umbrella moves with the royal court, it transforms and elevates the person it shelters, symbolically hiding their thoughts even from the heavens above. The exhibition, which was accompanied by a moving documentary, was thoughtfully structured to emulate the stages of an enstoolment ceremony, guiding visitors through immersive spaces that reflect the rich cultural tapestry of the Akan people.

I spent some time with Benissan in July 2024, while on a short visit to Accra. Our first conversation, which took place at Gallery 1957, was followed by a visit to her studio, located across the street from the gallery. We talked about her experience growing up Ghanaian in the United States, about the importance of religion and education in her upbringing. She told me how, in gradually understanding her hybrid identities as she came of age, she was able to navigate a disability and complete her Bachelor of Fine Arts in Apparel and Textile Design at Michigan State University before studying for a Master of Fine Arts in photography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 2021.

The conversation quickly shifted to Si Hene, a non-profit she founded in 2020 when she was in graduate school to preserve Ghana’s chieftaincy and traditional culture while ensuring accessibility to historical archives. The name Si Hene, meaning “enstoolment” in Twi, reflects her commitment to honoring the institution of chieftaincy—a cornerstone of Ghanaian culture and identity, embodying centuries of governance and customs. From royal decrees and correspondence to ceremonial regalia, oral histories, and photographs, she and her small team and trying to safeguard these fragile, irreplaceable cultural materials to ensure their long-term survival.

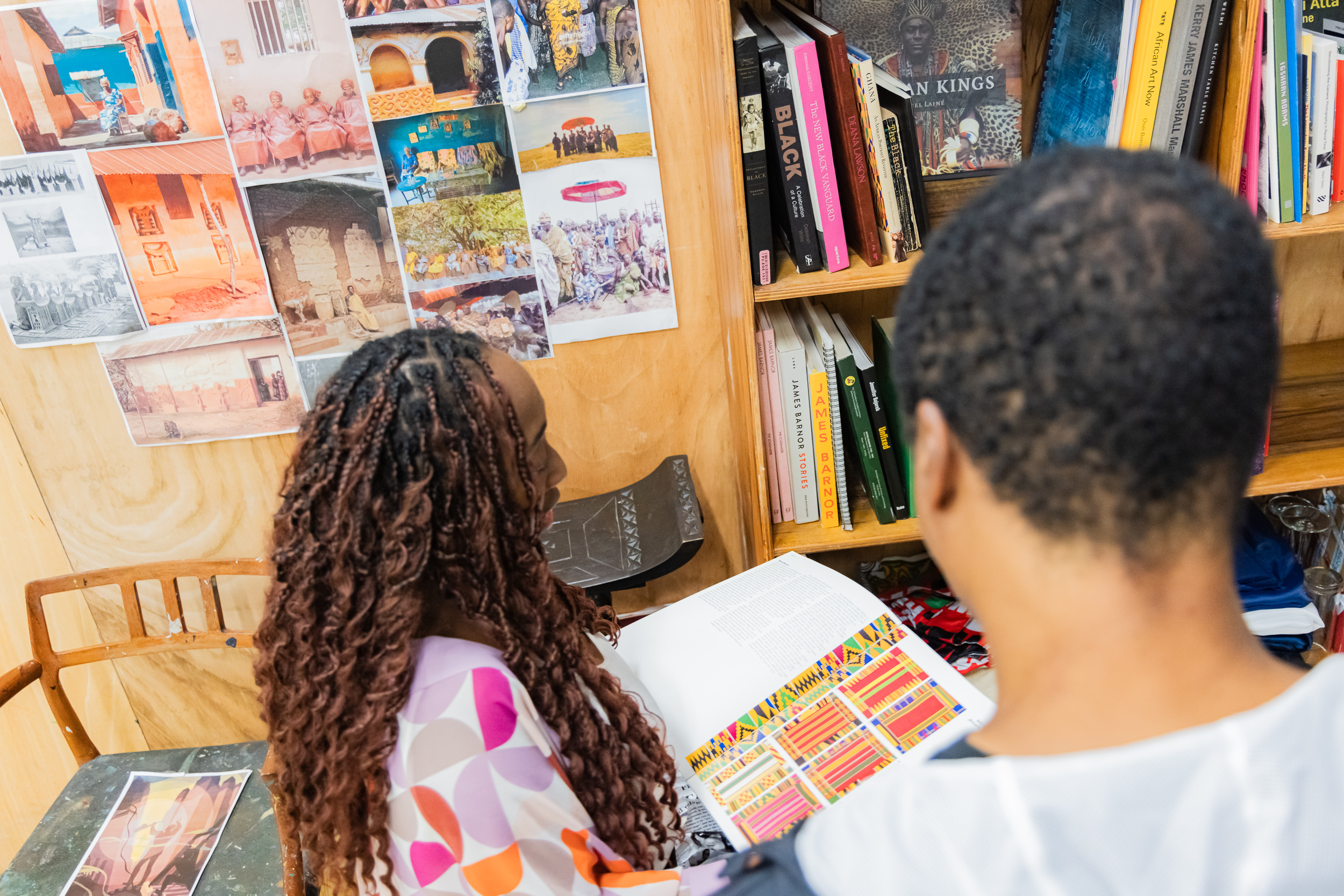

“Si Hene stemmed from my research with the umbrellas, and the lack of accessibility of photos of chiefs, kings, queens, and queen mothers,” she told me. “I realized when I was in my graduate program that I was able, thanks to my university email, to have access to a lot of online databases and information that would not be present in Ghana. I saw that as a big problem, and I realized that we should have access to our photos from the 1900s. We’ve had public acknowledgements and publications, and I’ve been interviewed about what I hope Si Hene can provide to the community, to Ghanaians, to those who don’t live in Ghana, or to Africans in general. I was able to work with the Open Society Foundations in the US, as an artistic director for their conference on restitutions. And recently, in honor of Ghanaian-British photographer James Barnor’s 95th birthday, we convened a community archiving workshop. My goal, within the next five to ten years, is to create a cultural center in Accra, and eventually in each of the 16 regions in Ghana, where people can experience this history and have this history be accessible to them. I see it as an extension of my art practice.”

I was deeply moved by the way Benissan spoke about preservation, and I loved the way she describes herself as a custodian of the royal history of Ghana. As a native son of Togo, I have always had an understanding and appreciation of neighboring Ghana’s unique contributions to world culture. Benissan seems hell-bent on safeguarding these records, with the goal of allowing future generations of Ghanaians in Ghana and in the Ghanaian diaspora to connect with their roots and maintain continuity in cultural practices, ensuring that country’s heritage evolves without being erased.

In many African countries, historical archives are at risk due to factors such as neglect, conflict, or environmental threats. Preservation protects these treasures from irreparable loss. By ensuring that these resources and research materials are available to all—students, researchers, artists, journalists, art aficionados, and the public—Si Hene seeks to democratize access to knowledge, empowering individuals to explore and learn. The debate around art restitution—crystallized in the success of Mati Diop’s award-winning 2024 documentary Dahomey—has led to a broader conversation around preservation, with many scholars arguing that awareness fosters understanding, challenging stereotypes and misrepresentations of African traditions while encouraging others to respect and learn from the continent’s rich history.

Benissan’s use of modern materials and techniques, such as 3D printing, which allows her to “remix” traditional motifs, is compelling because it invites viewers to engage with the complex dialogue between past and present. This juxtaposition, which underscores how technology can complement and enhance traditional skills, holds particular significance, because her work ends up challenging the notion that heritage is static or bound to the past. Instead, the works in progress that I saw in her studio portray cultural traditions as living, evolving practices that can adapt and thrive in modern contexts, bridging generational gaps and inviting continual progress.

The more I listened to Benissan, the more I realized that her work—particularly the pieces that give new meaning to ceremonial artifacts—is critically important in the new contemporary art landscape. It is opening new pathways in artistic experimentation because it addresses the urgent need to preserve, celebrate, and share Africa’s unique cultural heritage in a way that might resonate with the curiosity of future generations. Her artistic practice transcends the mere documentation of history; it actively engages with the dynamic interplay between tradition and modernity. By revitalizing endangered skills, she is ensuring these skills remain relevant and valued in contemporary contexts. Establishing new forms of collaboration, she has positioned herself as a cultural custodian who is adept at putting her finger on some of the elements which are central to past, present, and future African identities.