Since the 1996 death of my father, Mohamed Amin, an inconspicuous back room in my home and office in Nairobi has been locked off from the public, maintained only by two solitary sentries stationed between file cabinets in a windowless, climate-controlled vault.

Now, after years of not paying too much attention to this treasure, of not understanding this amazing resource, I want to bring the Mohamed Amin Collection to life. This Collection includes more than 5,000 hours of raw video content and approximately three million still photographs gathered between 1953 and 1996.

As a resource, the Mohamed Amin Collection represents one of the world’s greatest unexploited historical artifacts and includes unique, high quality documentation of the events surrounding post-colonial Africa, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Afghanistan.

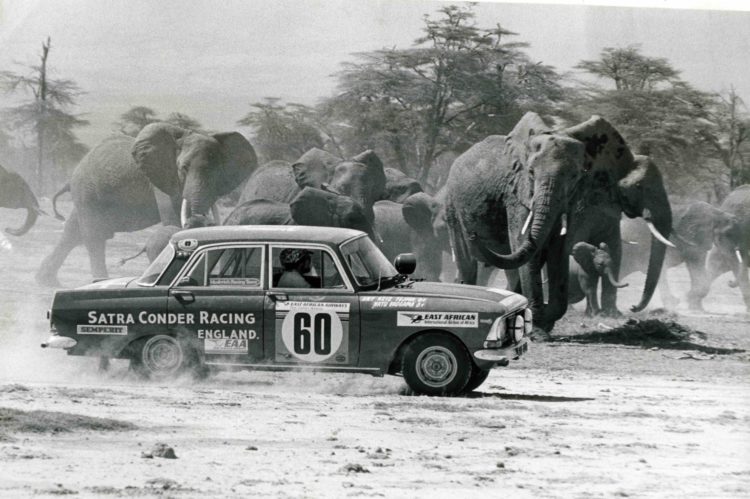

The Mo Amin Collection features both artistic and journalistic coverage of culture, conflict, political upheaval, wildlife, entertainment, wilderness, historical observation, and an unparalleled visual chronicle of the daily life of millions of people and places from around the world.

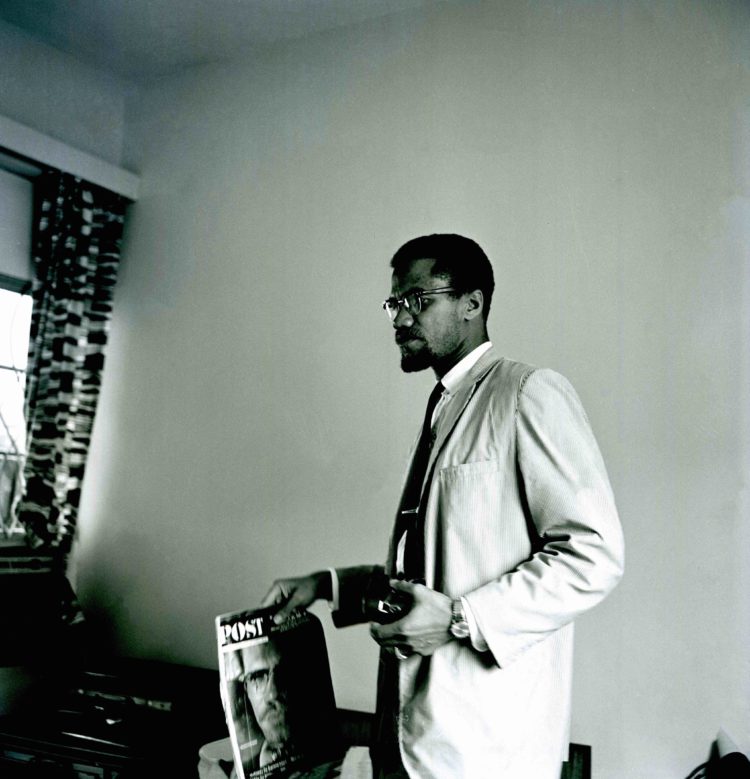

My primary mission is to translate and share this body of work with the global public as a way to stimulate dialogue about Africa, Asia and the Middle East. As an African photojournalist, my father never had to parachute into a news story on the continent.

He was already on the ground working lifelong contacts with chefs and soldiers, shop owners and security guards, government officials and revolutionaries—relationships he’d built up during decades of tenacious networking.

He was already on the ground retracing routes by Land Rover and Cessna, on motorcycles and on foot, routes through villages and slums, army forts and palaces, coffee shops, and corporations, for newsrooms in Kenya, the UK, Canada and America starving for a scoop.

Much like Africa, my father was caught up in a tide of change from an early age. From humble roots in Dar es Salaam, he was swept up by the turmoil of a continent locked in revolution and shackled by poverty. He was prolific by any standard, yet his mission was singular in its focus – telling the story of Africa and Africans.

And like Africa, his professional journey included crisis and chaos, beauty and majesty, and a deep, resonate passion for documenting and protecting the best of the continent while moving fearlessly forward into an uncertain future. Although it’s a rare and sacred thing, a singular event can change a continent… and a man.

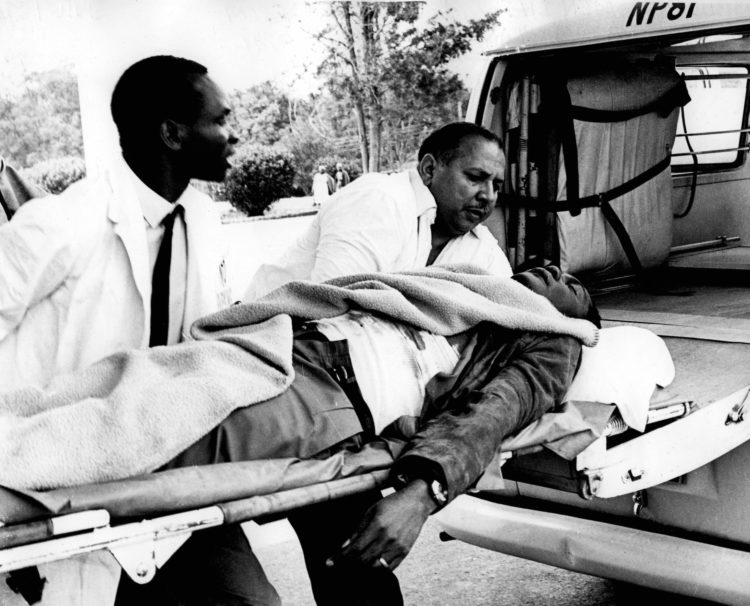

When millions die as a nation uses food as a weapon of war, the worst instincts of humankind fly in the face of logic and decency. Yet that is what happened in Ethiopia in 1984. Mohamed Amin was there with his cameras to document the suffering.

His images changed the world as the people of Africa and the world responded with the Live Aid concerts, one of the greatest acts of philanthropy in human history. The famine was a tipping point for him personally and he changed for the better—he became a better man and a better father.

Africa changed for the better as Africans united in their humanity and the quest to overcome the suffering that had long defined nations rooted in the malaise of colonialism and conflict.

Now, by telling the Mo Amin story through the power of photojournalism to inspire change along with the beauty and complexity of great photographic art, I plan to share these rare, historic moments for the first time.

The timing is right for so much of the world. South Asia, Africa and large parts of the Middle East are immersed in a tide of unprecedented economic, cultural and social development. The United States, Britain and Europe are finding their past sins coming back to haunt them. And the recent history that drives the present is well articulated in the stories and images represented by this Collection.

I didn’t really understand the power of the camera until I had an opportunity to study my father’s work. Photojournalism can make a difference and his images moved the world. He forced people who were indifferent to have to know, to no longer be able to turn a blind eye, and this was the greatest use of his gift.