The press preview for the Beauté Congo – 1926-2015 – Congo Kitoko exhibition at the Fondation Cartier in Paris was equal part showmanship and confrontation.

On a hot, July, Left Bank afternoon, a group of mostly French and Belgian journalists were gathered alongside a few elegant Congolese critics and African art practitioners. We were there for a question and answer session with some of the figurative painters taking part in the first ever retrospective of art from the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The show, a rare achievement, consists of 350 paintings, photographs, sculptures and comic books from 41 different artists, but the stars are undoubtedly the figurative painters from Kinshasa. For this preview, big names like Chéri Samba and Papa Mfumu’eto were lined up on a panel next to emerging talent like Kiripi Katembo, Steve Bandoma and Monsengo Shula. It didn’t take long for chief curator André Magnin, arbiter and exporter of Kinshasa’s art movement for three decades, to become a prime target of criticism and what appeared to be deeply-rooted resentment over his ‘French’ perspective.

These were disagreements over the lack of female representation, Belgian colonialism, the chosen methods for classifying the Congolese population and the historical meaning of such a groundbreaking exhibition. I was seated in the fourth row, preparing to take a group shot of the panelists with my phone, and a middle-aged Congolese woman seated not too far from me stood up, raised her voice and starting arguing with some of the artists in Lingala, Kinshasa’s main Bantu language. A French lady appeared, seemingly out of nowhere, and inserted herself in the argument, insisting that, in France, one should speak French, not Lingala. Nothing out of the ordinary, just a typical Kinshasa diaspora salon, one might conclude, with the charm, conflict and intimidation one has come to expect from such a passionate people.

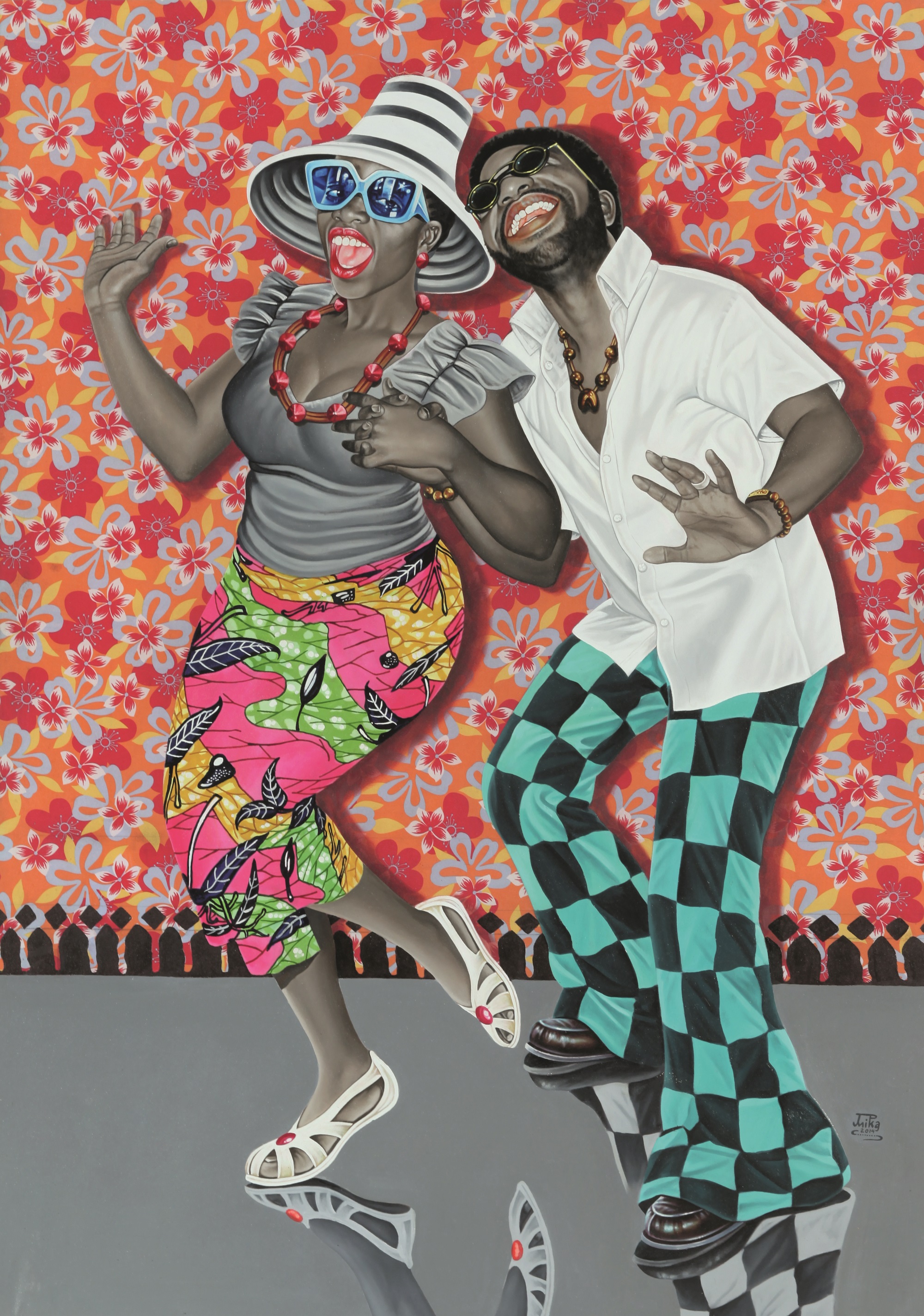

On the far end of the panel, one young man remained mostly quiet throughout the debate, and it struck me that he should have a lot to say, given that his image Kiese na Kiese – Happiness and Joy – a colourful image of a stylish young couple dancing feverishly to the backdrop of floral wallpaper – was chosen for the exhibition poster and catalogue cover. In the catalogue, I had read that JP Mika was born in 1980 and had studied painting at the Académie des Beaux Arts in Kinshasa. Picasso was one of his inspirations, as were the Malian photographers Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta.

Mika is represented by André Magnin’s MAGNIN-A gallery, hence the accusations related to various levels of conflict of interest. What I found most interesting was that he had honed his style while working at the Atelier de recherche en art populaire (ARAP) under his mentor Chéri Chérin, one of the stars, alongside Chéri Samba and Moké, of the seminal 1978 Kinshasa exhibition Art Partout. After the debate ended, each artist returned to the museum galleries and posed for photos next to their best work before answering questions individually.

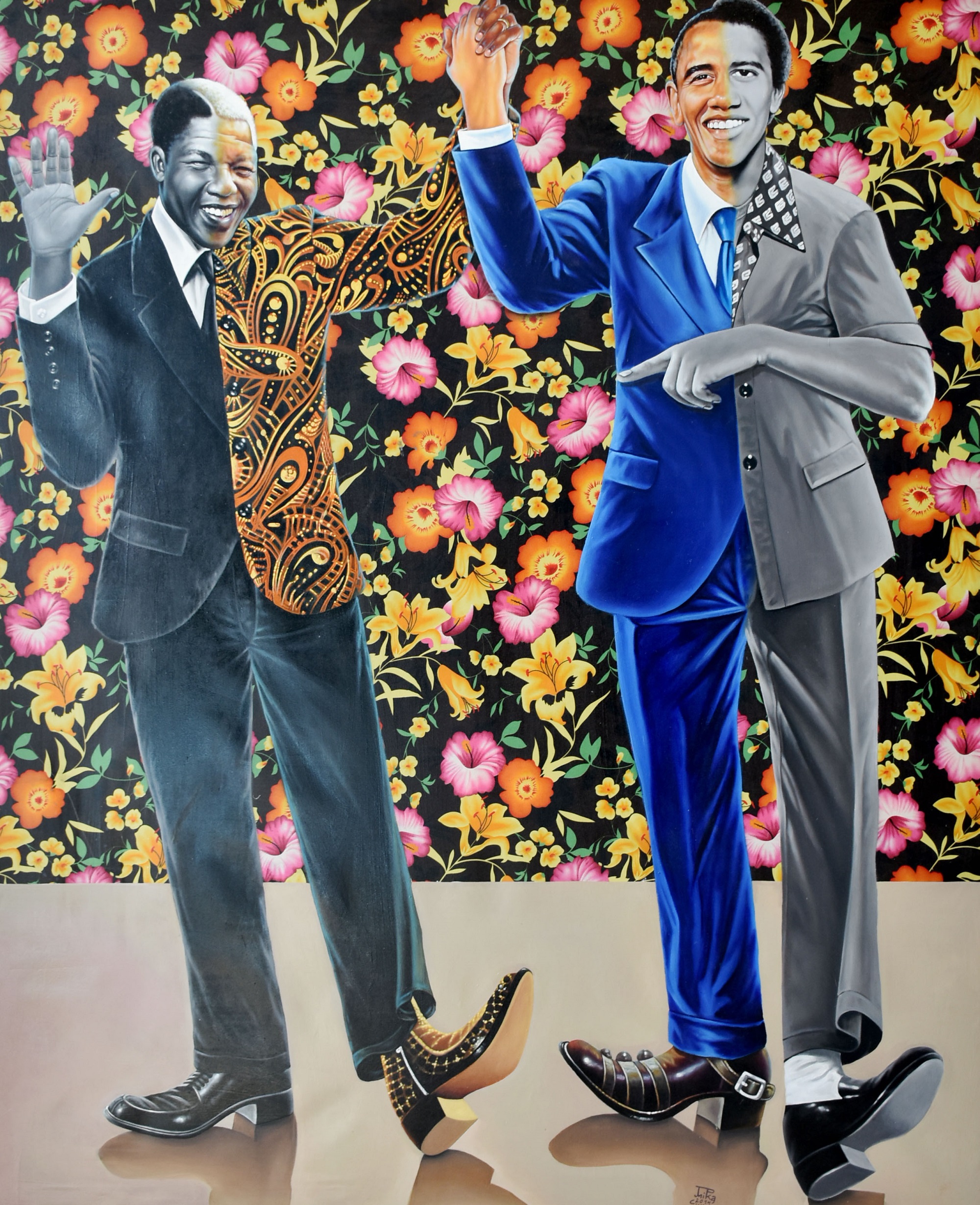

Chéri Samba was the main attraction, but in another gallery I saw that critics were also lining up for interviews with Mika. When it was finally my turn to ask questions, I told him that I was intrigued by Mandela dignité pour l’Afrique, the portrait of Nelson Mandela with Barack Obama, my two heroes. A lot of people were talking about La Nostalgie, a portrait of a joyful young girl sporting oversized white spectacles with a green wax-print dress and multi-coloured sandals. But I was particularly drawn to the sizing-up, wising-up narrative he’d implied in the way he split Mandela and Obama’s adult frames and juxtaposed the young activist with the older politician, all the day down to the mismatched black leather shoes.

‘I wanted to add some strength to these images, because these are the men who represent Africa, different views on Africa, and everything about Africa is half-half. What I did with these images is very hard to do, technically, but this was my way of showing that I can do, that I am now able to do all these things. People love this painting, and as a matter of fact, I’ve already sold it. It sold very quickly. This painting is one of those that allowed me, in my own way, to emancipate myself, to find my own techniques that were different from those of my master Chéri Chérin.’

Then, I asked him to stand next to the self-portrait, called La SAPE, my favourite painting of his in this group show. La SAPE is an acronym that refers to the ‘Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Elégantes’ – the Kinshasa (and Brazzaville) sapeurs.

‘In our city, down there in Kinshasa, so many young people are trying to be sapeurs, crafting their entire identity around their clothes, their poses and the way they choose to assemble their own style. The people of Kinshasa are my main source of inspiration and I was thinking of a way to show this sape obsession in a different way. So I though to myself how I wanted to imagine, to create, to paint something that is pure, that is 100% Congolese. The wax fabric that people like to wear, the way they pose, the way they try so hard and want to get noticed. But I added my own twist to the Congolese sapeur style. I turned the belt into a tie, and went a bit crazy with the wax print hat and the crocodile boots.’ Would you dress like that? I asked him. ‘I haven’t dressed like that. At least not yet. So far, I’ve only imagined it.’

Beauté Congo – 1926-2015 – Congo Kitoko is at the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris until November 15, 2015.