Hip-hop culture is something new in Mali, a highly conservative society known for the traditional music of the griot and oral musicians. But a new generation of artists is changing this.

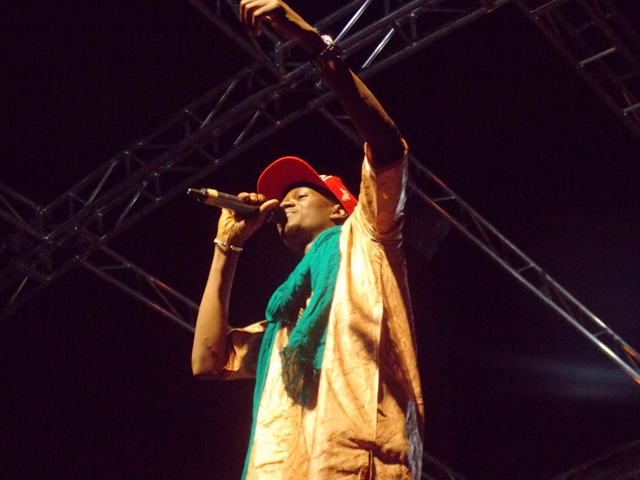

Lawyer and activist, Ismael Doukouré is also known as Master Soumy, a hip-hop star from Bamako. He writes and raps to fight against bribery and corruption and to promote good governance in Mali.

Please introduce yourself to us.

My name is Ismael Doukouré but I am also called Master Soumy, musician, activist, artist and rapper.

I am Muslim by faith and Rasta by conviction.

I am trained as a lawyer. I am Muslim by faith and Rasta by conviction.

Can you tell us a bit about your childhood?

I had a pleasant childhood. My origins trace back to the Soninke clan and I grew up in a Bambara family. I was educated by my grandfather from my mother’s side. He was the one who drew me the path of life. First of all, in terms of education: in our family I was lucky to be the only boy among twenty other brothers to attend formal school and university. This was thanks to my grandfather.

He taught me a lot of things and helped me to understand a lot of things about the cultural heritage of Mali. Even in my music he is the one who guided me and gave me inspiration because he was himself a great revolutionary.

How did you get into hip hop?

I spent my entire childhood listening to hip-hop songs of American and French artists… and Africans ones too – including some artists from Senegal like Daara J and PBS.

Hip hop was made to denounce injustice and social inequality.

At primary and secondary school, I’d copy these artists, performing with friends. But in the end, I decided to create my own music.

Hip hop can be traced back to American ghettos. How did you enter into the industry?

Well, I have done a lot of research. At the beginning, hip hop was devoted to change. Hip-hop music was made to change behaviour: to leave the bad and go towards the good.

Hip hop was made to denounce injustice and social inequality. It was meant as a way for black men to reevaluate themselves because in American ghettos the life of black people could be very hard.

As I was really interested in bringing a change in my own community, I entered into the hip-hop industry.

Can you explain the themes that have developed in your hip-hop music?

I have developed a lot of themes in my music but most of the time I talk about leadership. It’s the governors who must lead our country. They were elected to lead our nation. We have a contract with them.

They have a right and a duty. But if their mission is not executed, we have a right and duty to denounce them. Generally, in my songs I want to raise awareness, provoke thoughts and push people to see things clearly and assume their responsibilities. It’s not only about the governors but it’s also about the population: we are the two halves which form the republic.

What characterises your hip hop?

I created the ‘Galedou System’, a rhythm based on the cultural heritage of the Mandingo dialect, Bambara. Whenever I use a Bambara quotation in my song, I use it in a way that will make my audience laugh.

Mali is very rich when it comes to music; there are more than 700 ethnic groups in this country and each one has its own music and dance. We must preserve them.

Music is meant to make people fun and happy and laugh. Actually a lot of people have adopted my style. But, to be honest, I created that style in order to mark myself out from other rappers.

Did you talk about the cultural heritage of Mali in your hip hop music?

I use Malian traditional musical instruments like the n’goni, kamalin, balafon, djembe, tamani and so on… using the cultural heritage of Mali is one of my priorities. It’s important to educate the younger generation about traditional musical instruments and our local dialects.

Mali is very rich when it comes to music; there are more than 700 ethnic groups in this country and each one has its own music and dance. We must preserve them.

We know that Malian society is a highly conservative society so how hip hop music is perceived here?

I would like to pay tribute to people like Mr Lassy King Massassy, the founding fathers of Malian hip hop, as well as the other journalists who risked their careers to broadcast hip hop including Salif Sanogo and the Modibo soirées.

Today, thanks to God, rap concerts fill stadiums. This is because rap music is one of the best forms of music to listen to. I am among the third generation of Malian rappers. Before it was rappers like Tata Pound and Fanga Fing who showed that rap music is not music for delinquents but one which spreads a message.

You talk a lot about problems in Mali. What about peace?

First of all, I am worried that people don’t understand my message… Many artists talk about peace but we have peace. I explain myself it’s not good to always go out and say we need peace and deprive Mali of its role in making peace.

Malians are thirsty for information but the Malian government doesn’t inform them.

Apparently the framework of the peace treaty is ongoing, I don’t think there is a will to respect that framework; I think that there is only a process of division, a partition of our country. For example the Kidal region; apparently everybody is free to go to Kidal. Everyone apart from Malians, or the Mali administration it seems.

We all need peace. Even when musicians put on a concert, we need a secure environment. So I think that peace is the starting point; peace must go with justice, peace must go with good information… Communication is different from information.

Malians are thirsty for information but the Malian government doesn’t inform them. That’s why brainwashing becomes a reality. Today when we talk about our Touareg brothers, I think that the MNLA use become a political party.

The solution of this crisis is not military; it’s cultural.

I’m a democrat and a republican. Movements must transform themselves into political parties in order to defend the interests of their community rather than using weapons. The solution of this crisis is not military; it’s cultural. We must put culture at the heart of the debate. Leaders must give opportunities to artists to work hard in this crisis and fight against violent extremism that is affecting the entire world.

Culture is a method of communication and allows people to understand things in a society. Generally, most people cannot understand information in print or on radio or cable. But, in music, the message is clear.

What do you think about the diaspora?

First of all, I would like to thank the diaspora which has really helped Mali. When you visit certain villages in Kaye, you feel like you are in a city because of the infrastructure provided by the diaspora.

But I have a message for the diaspora: the problem of immigration concerns us all. The diaspora should raise awareness about the need for legal ways of going abroad. It should not be about financing their brothers in villages; they will try to escape by sea but in the end they will die there. We don’t need to kill ourselves just to go to the other parts of the world. Western countries must see what they are doing is pure politics. Everybody comes to our country and we accept them. There is need for debate and more understanding about immigration.

Do you think that hip hop can be a catalyst for fighting against violent extremism in Mali and bringing lasting peace?

We already have started the fight because we have a group of rappers called the Ambassadors of Freedom of Expression, a group created by ‘Ciné Droit Libre’ supported by Art Watch. We are 12 artists from eight African countries like Mali, Benin, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Niger, Côte d’Ivoire, Mauritania and Senegal. I am Mali’s representative.

We have already sung our first song Le droit de vivre (The right to live). This song talks about violent extremism and the fight against the radicalisation of young people in villages. It’s important to highlight that poverty is one of the key reasons for radicalisation.

What future do you see for Mali?

I love Mali so much but am pessimistic about the future of this country. If we want people to take us seriously, we have to be serious.

You are working on a new album please can you talk about us this album?

My new album is called GWELEKAN. It has 10 songs. It took me two years to make. In this album I sing about the current political security problems in Mali.

What’s your message for peace for Mali?

First of all, I would like to say that if you need peace we must tell the truth to each other. Do you know why in Mali we have problems? It’s because we always tried to find a way out but instead we must solve problems.

If a country does not have its own educational system it will be a slave of other countries.

The Malian government must promote education and implement a educational system. If a country does not have its own educational system it will be a slave of other countries. We must all promote social cohesion and national reconciliation in this country.

What’s your last word?

I would like to thank you for giving me this opportunity to talk to you. I also encourage all your collaborators for the great job you are doing in this country in terms of the promotion of its cultural heritage and all you do for Africa and the entire world.

So we thank you so much in the name of the Timbuktu: land of peace and culture.