‘Do you sometimes hear voices or see things that aren’t there?’ My psychiatrist’s question, the first time we met, was one in a series of similar inquiries designed to gauge what level of batshit crazy I was on.

While the diagnosis was pretty clear – depression with a touch of anxiety – he still wanted to know whether there was a chance that there might be other underlying/repressed issues (and possibly a reason to give the pharmaceutical companies more money, the scammers). I had to think quickly before I answered and with every passing second I thought, ‘This wouldn’t happen if my psychiatrist were African because they’d get it.’

My psychiatrist is an old European man who despite having been in Africa for longer than I’ve been alive still understandably has some reservations about our customs and beliefs. I don’t hold it against him because, well, a lot of people feel a way about things they can’t understand or explain.

I’ve seen spirits all my life.

I also assume – what with him having seen his fair share of situations where a person’s mind has created all kinds of realities – he’d be less likely to be understanding of supernatural things than the average person. So when he asked me that question, I froze. I thought about the possibility of being wrongly diagnosed as schizophrenic and what that would mean for me. Then I wondered whether trying to explain to him that yes, I do occasionally see and hear things I logically know aren’t exactly there but I’m very aware of that and at no point in time do I lose touch of reality would in fact fall on deaf ears or not. Would I be a ‘backward African’ in his eyes, or would he turn out to be one of the few foreign doctors who actually respect our beliefs?

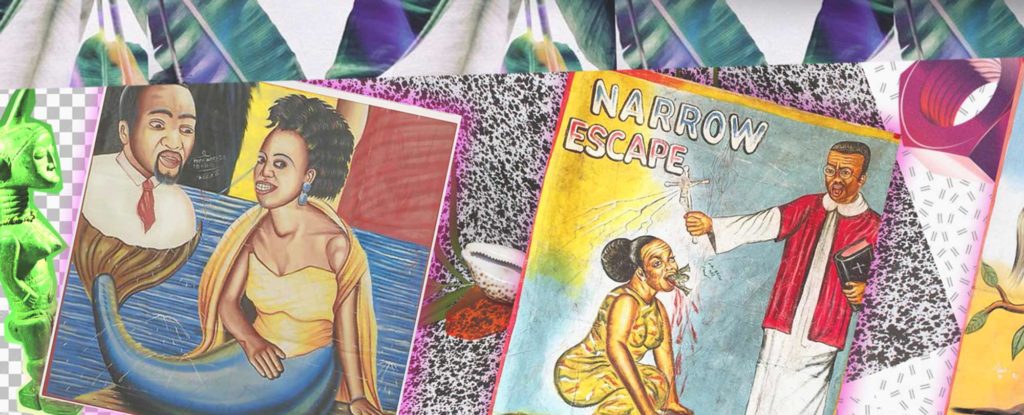

While many people believe in a sixth sense and the supernatural to a certain extent, most don’t pay it much mind out of a fear of the unknown. Beyond God and certain Biblical figures lies powerful and potentially malicious forces many don’t want to acknowledge, no less interact with. And yet for many young Africans, no matter how progressive we think we might be, a connection with the spiritual realm is something we simply have no control over.

I’ve seen spirits all my life. From as early as four years old, which is when my memories begin, all sorts of characters would appear before me and I learned very early on that the things I saw seemed to be for my eyes only. The adults around me who prayed feverishly in a bid to get a glimpse of the divine would chastise me for my gift of sight and I eventually knew not to talk about the spirits of miners I’d see walking past our window at night, deep in conversation about their families and jobs, or the sangoma on a giraffe in our neighbour’s yard. It was simple, if no one else acknowledged it, it wasn’t there to them and I therefore minded my business.

While some experiences were scary in the beginning I eventually learned to deal with them and after a while knew how to react to certain situations, if I reacted at all. I knew and understood that this was simply a part of my life and in no way a sign of mental upset. Some people experience a closer relationship with the ‘other side’ than others and I was one of them, that was all there was to it.

In all those years (five to be exact) all I ever got was advice to go to church and speak to my parents about my feelings.

As I grew and shared these experiences with other people who’d had similar experiences my comfort with them was validated – I wasn’t the only one and I wasn’t mad either. As I watched some of my friends get the calling and become Sangomas, I became more comfortable with straddling this world and the next. In all my years the people I discussed it with were never medical professionals for a number of reasons.

From the time I saw my first psychologist at 16, an elderly Tswana woman running her own practice, I have picked up on a few things. There were also numerous Varsity councillors (in my defence, they’re free) all of African descent and all of course, Christian. That didn’t bother me so much because one’s personal politics are just that, personal. But I realised that all professionalism went out the window once they were confronted with a patient they deemed a ‘spiritual challenge’. In all those years (five to be exact) all I ever got was advice to go to church and speak to my parents about my feelings.

It baffled me that these people had graduated, but more so, why they’d spent that many years learning absolutely nothing in the first place. They stopped being medical professionals and dragged their religion into sessions, every time.. Sharing my personal spiritual experiences would have earned me an exorcism and nothing more, and I didn’t need that.

I lost count of the number of times the people I saw called my mother and told her everything I’d said, sometimes immediately after the session was done.

The second reason was the blatant disregard for patient doctor confidentiality they displayed. I lost count of the number of times the people I saw called my mother and told her everything I’d said, sometimes immediately after the session was done. Now this would have been understandable had I been at real risk of self harm or something but I wasn’t (well, I was but they didn’t know that) so the constant snitching only added to my distaste for them – My mother getting a call about how I saw things that weren’t there and believed that it had something to do with the fact that my paternal grandmother is a witch would probably have driven her to the madhouse.

For a long time I was convinced that Africans in the psych fields were simply unprofessional and yet they were all I was exposed to. I longed for a different experience and I got it when I met my current psychiatrist but that joy was short lived because I found that while a foreign practitioner may be professional they simply could not grasp how things like callings which led to seeing spirits and making eerily accurate predictions on life altering matters like life and death could be an everyday part of life without it somehow being an imbalance. As I sat across my psychiatrist on that day mumbling through my explanation for seeing and hearing things that aren’t there I wondered, where the hell are all the young African psychologists and psychiatrists I’ve known over the years?

Sure, people are kinda sorta pretty much all the same but the mental health of a person from an Amazon tribe and a Holocaust survivor cannot be treated the same.

It’s as if they disappear off the face of the earth a few years into their course and just never resurface. That’s unfortunate because if anyone’s going to soothe the disconnect many patients have using western medicine and balancing it with our non-Christian traditional spiritual and cultural beliefs, it would be them. Their experience of both sides and the open-mindedness of youth (although that isn’t always the case, but I’m hopeful) means they could create safe environments for patients to discuss all facets of their mental health and the issues behind it without having to worry about being misdiagnosed by a cynic or converted by a religious fanatic.

The older I get the more I realise the necessity for mental health services which are tailored to the people of a specific region. Psychology isn’t one size fits all (shout out to UK’s recently launched recovr which seeks to hook black youth up with black therapists as we try to tackle this global issue). Sure, people are kinda sorta pretty much all the same but the mental health of a person from an Amazon tribe and a Holocaust survivor cannot be treated the same. One’s background plays an important role in the person they become and beliefs are a large aspect of that.

So where are the African psych graduates? Do they get swallowed up by government hospitals? Are their degrees somewhere framed on their parent’s wall in the farmhouse while they pursue other ventures in the big city? Do they really exist or are they a figment of my imagination? A fantasy conjured up to counter the shitty and possibly traumatic experiences I’ve had with the oldies in their field?

I need answers. Not just for myself, but for the culture, as the kids say, and possibly for the future good of the continent.

This is part of a guest editorship series by Bakang Akoonyatse. She’s producing a series of pieces for TRUE Africa as a Guest Editor. More here.