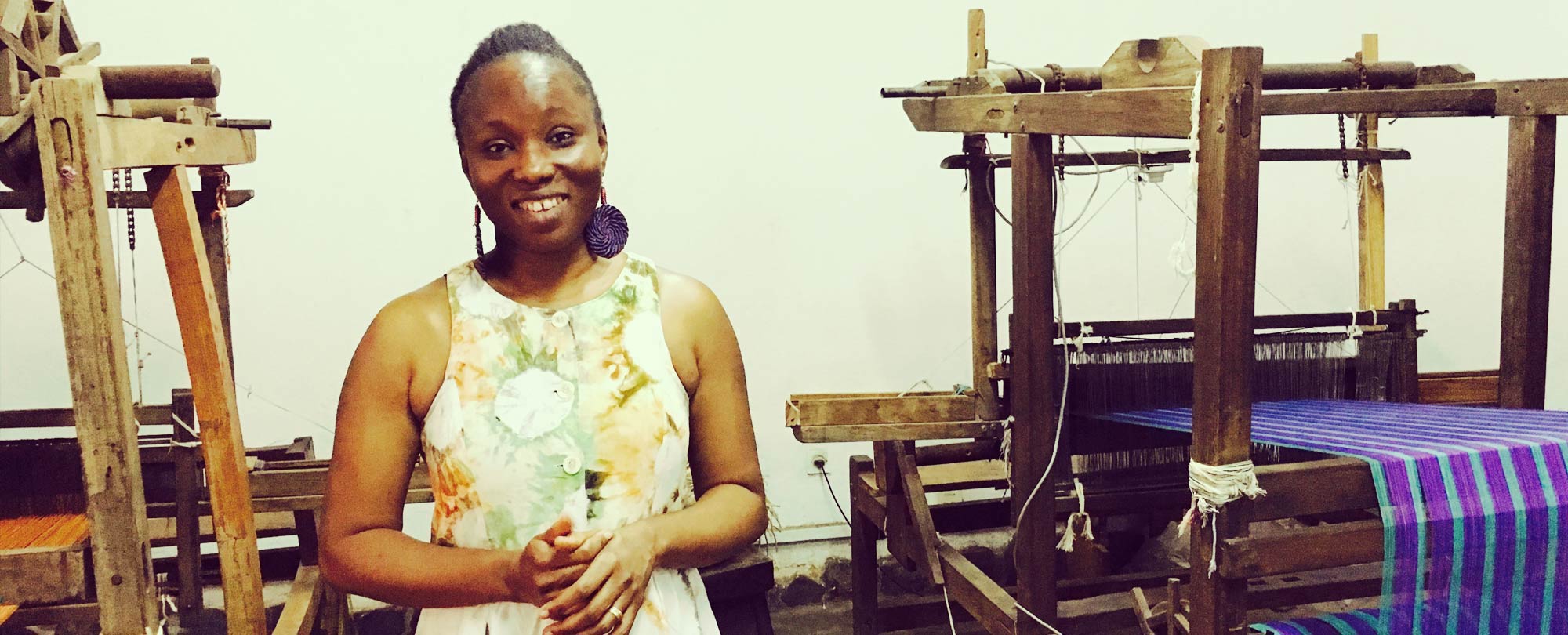

Awa Meité van Til’s studio in downtown Bamako is tucked in the back of a complex called the Centre Amadou Hampâté Bâ, named after the famed Malian novelist and national hero. When I visited her there last month, I was greeted by Awa’s mother Aminata Traoré, a former minister of culture and tourism in Mali, her son, and a group of elegant boubou-wearing ladies chanting away in Bambara like Sahelian sirens.

I’d heard about Routes du Sud, which Awa had created in 1998 as an organisation dedicated to preserving and showcasing Mali’s craftsmanship in various areas related to textile design. Sekou Coulibaly, a Malian executive at L’Oréal in Ghana, had told me about Awa’s network of artisans across Mali. Once she became vocal about her desire to reinvent the value chain, Awa was known as the local girl who’d contributed to employing those undervalued weavers and seamstresses who knew how to make a beautiful African accessory.

People who know Awa talk a lot about her relationship with the legendary photographer Malick Sidibé and his family, about her faith in Africa’s traditions and ancient techniques, and our conversation was very much about that new sense of pride in Africa’s fashion industry, in Africa’s creativity. That pride is being driven, she told me, by global export ambitions. As soon as we began the interview, Awa said, ‘With all these world cultures cross-referencing each other, this is the moment to show the world that Africans can create superior products in the fashion industry.’

Her gusto for creativity, combined with deep emotional intelligence and acute marketing instincts, seems to result in real excitement.

There is a terrific energy of inspiration radiating from the objects that Awa has assembled on and around her desk. From the French-Lebanese writer Amin Maalouf’s book Origins, which sits on the wooden shelf next to Tariq Ramadan’s tomes on Islam and Air France’s in-flight magazine Madame, to the hand-crafted bowls and utensils from the 19th century, the feeling is all about heterogeneity.

Even though I visited on a Sunday afternoon, I could tell that the workplace was fun and serious at the same time. From the way she treats her employees, including a young assistant called Dala Kanouté, one can tell that this chief creative officer is kind and demanding at the same time. Her gusto for creativity, combined with deep emotional intelligence and acute marketing instincts, seems to result in real excitement around a creative process that is all about collaboration and fair trade.

Awa, who was born to an Ivorian father, grew up in Côte d’Ivoire. Awa’s mother was best friends with the Malian fashion designer Chris Seydou, a one-time assistant to Yves Saint-Laurent who made his mark in eighties Abidjan with popular miniskirts which he reinvented by using mud-dyed cloth. Seydou died in 1994, and Awa named him as one of her main inspirations. ‘My mother was always hanging out with artists, and those are the people I was around when I was growing up. Early on, I was able to see, first-hand, how artists work.’

‘The freedom that we found in Bamako was real, because we felt that we’d finally found home.’

At 15, Awa was supposed to go to boarding school in France, because the plan was to be equipped with some of the cues that come with an understanding of French culture. Instead, the family moved from Abidjan to a new house in Bamako, where Awa began to gain an awareness of the broader possibilities around creative expression. ‘The freedom that we found in Bamako was real, because we felt that we’d finally found home. My mother was a mondaine, and because she loved entertaining her artist friends in the new house, in this house, she always found a way to invite people to discover the creations of the local artisans.’

When her mother took a job at the United Nations in New York, the family was transplanted once again. ‘The great thing about the American mentality is their motto “sky is the limit”,’ she says. Awa felt grateful for the opportunity to study alongside Americans who were driven and ambitious, yet she credits an anthropology class she took at Stony Brook University in Long Island (outside New York City) as a defining moment that led to her future career.

‘The professor, an American lady, was so knowledgable about Mali, yet I couldn’t relate to any of the things she was saying about my country. In class, I felt ill at ease, because it was as if the Professor was talking about a Malian culture that didn’t exist, at least not in my eyes. I didn’t want to contradict the professor, because she was an “expert”, but I did come to the conclusion that as a Malian I should learn more about my own culture.’

After graduation, she took a year off, and started traveling across Mali by bus. She was welcomed into people’s houses, in the most remote villages near the Mauritanian border. ‘It gets very hot there,’ she laughed. ‘It’s very easy to get dehydrated in those villages.’ That is when she decided to find a way to work with those women. ‘The village women had embraced me, had shown me so much love, and I wanted to help them in my own way, but I thought we should think of working together to create something better than the same old baskets they kept weaving. So I started talking with them about business, and once I saw that they had adopted me, I came up with the idea of a festival that would help to promote these local cultures.’

In 2007, Awa created the Daoulaba Festival, now in its ninth edition, around a series of concerts, exhibitions, fashion shows, and debates about the preservation of local cultures.The festival, which was based on the same local empowerment philosophy as the Routes du Sud project, helped Awa think through what her big idea might be. The discussions with local creatives — and local farmers — allowed Awa to bring to the table some savvy judgment about modern distribution models, new technologies and particular products and services that could directly impact the villagers and their livelihood. She came to realise that organic cotton was where it was.

‘For me, it’s about pride in knowing that our products have real value.’

Helvetas, a Swiss association for international cooperation, had become the first port of call for many Malians looking to produce organic cotton. Helvetas had developed a successful training program across Mali, and their sustainable production model — based on bypassing the intensive use of chemical pesticides — seemed to be working for many of the most destitute communities. When Awa approached Helvetas, they weren’t interested in working with her. Neither was CMDT, the state-owned Malian textile governing body.

Because she spent a lot of time thinking about the business model, she knew which kinds of channels might make sense for her and her new business partners. After many months of negotiations, Awa was able to secure a verbal agreement with a group of women in a village called Sho. A couple of years later, she started exporting locally produced garments and accessories to high-end European, American and Asian boutiques.

When she felt short-changed by her foreign partners, Awa withdrew, leaving money on the table. ‘For me, it’s about pride in knowing that our products have real value.’ Some Malians credit Awa with pioneering a new, well-thought-out, ROI-based philanthropy. I personally think her story is not actually about philanthropy. When I saw Awa again in Paris earlier this week, when she was receiving yet another female achievement prize at the French Ministry of Culture, I felt that her success story represents a new way to interconnect people and move the world in the direction of a more positive economy.

Find out more at daoulaba.org and awameite.com