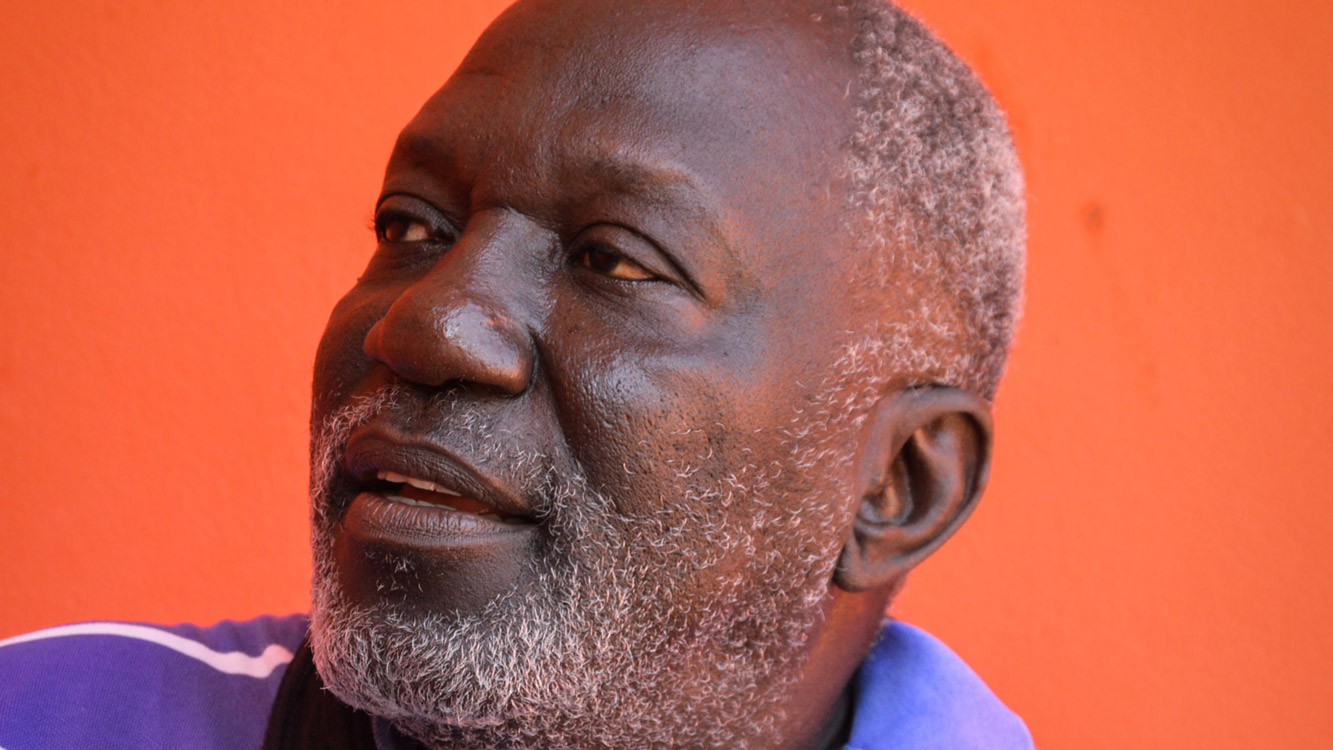

Paulo Gomes is a former leader of the World Bank’s sub-Saharan African region and now advises African heads of state.

He uses the word ‘exorcism’ to explain the process and series of events that led him to produce a documentary on Amílcar Cabral, the Guinea-Bissauan and Cape-Verdean engineer and freedom fighter who has become a bit of a cult figure for many young West-African rappers and activists.

When I met him in early March for an interview at a hotel restaurant in downtown Conakry, we agreed to discuss his new pet project. Gomes described his country, Guinea Bissau, as a failed state in need of an intervention, as if the nation and its soul had become victims of a new form of demonic possession. Gomes described a country where nothing works; where people live in fear; a country that has lost its soul.

A documentary devoted to a national hero can become a cultural statement.

If, indeed, the country is possessed, then inspiration — and hope — can surely be found in ancient traditions and in the most notable historical and political achievements. Surely, with many of the current leaders having lost their mind, a documentary devoted to a national hero can become a cultural statement that might help to evict demons and other spirits that are preventing the country and its citizens from moving forward.

52-year-old Gomes, the first Guinea Bissauan to graduate from Harvard University, tried to ward off those demons once before, when he ran for president, alongside 12 other candidates in 2014. The country of 1.7 million is often in the news but mostly for the wrong reasons. Guinea Bissau is plagued by rampant corruption and cocaine trafficking, and even through Gomes ultimately failed in that political moonshot, he hasn’t given up on trying to cast out those national evils.

Listening to him talk about his hero, the Cabral documentary project starts to feel like a follow-up effort that might be meant to eventually turn around a nation’s fortunes and inspire other Africans into action. ‘Cabral was at the root of the independence movements in two countries, Cape Verde and Guinea Bissau, which is completely unique,’ he told me.

Gomes talks a lot about how Cabral’s influence spread to revolutions in countries such as Angola, Mozambique and even Cuba. He never fails to mention Fidel Castro’s admiration for Cabral, or Cabral’s influence on the civil rights movements in the United States, or the way in which Cabral was invited to the Swedish Parliament in Stockholm.

‘Contrary to many Marxist theorists who got bogged down by the dogma,’ Gomes said, ‘Cabral established a framework for political action that was completely African, where Africans could take ownership of their own story, where Africans could understand their own history, their role in Africa and what they could contribute to the wider world.’

Gomes says that, even though, during the Cold War, he was being courted by both China and the Soviet Union, ‘Cabral maintained a certain level of independence, which was non negotiable. One of his favourite sayings was, “For those who want to help us, the only condition is that there should be no conditions”.’

Gomes’ friend and fellow countryman Flora Gomes (no relation) sat alongside us during the interview. Trained at one of Cuba’s leading film schools, he is one of Guinea Bissau’s most respected filmmakers. As the director of the Cabral documentary, he is another person fighting to preserve Cabral’s legacy by spearheading the development of the project.

‘I was 14 years old,’ he remembers, ‘when the armed liberation struggle led by Cabral reached my birthplace of Cadique in the Southern Guinea Bissau region of Tombali, which borders the Republic of Guinea. This is where the war started in January 1963. My family was active, mobilising the local population for the cause of independence.’

‘I became closely acquainted with Cabral.’

His family sent him to Conakry where he became one of the first students to enroll in the Escola Piloto, the pilot school that was established by Cabral to educate the children of the militants as well as the fighters in the liberation movement. ‘It was in Conakry that I became closely acquainted with Cabral, who left a deep and enduring impression on me.’

Cabral nurtured young Flora’s dream of becoming a filmmaker when he said to the students at the boarding school, ‘Tomorrow, the duty to tell our story will be yours.’ Amílcar Cabral was assassinated in Conakry on January 20, 1973, by members of his own African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde who were secretly working for Portugal’s secret police.

When today’s historians describe the ways in which Amílcar Cabral helped to defeat the Portuguese, they usually refer to him as one of Africa’s most influential anti-colonial leaders, a guerrilla fighter and uncompromising internationalist who brought his own brand of revolutionary socialism to the most remote corners of Africa. Both Paulo Gomes and Flora Gomes feel that they were born to tell this story of struggle against imperialism, a story just as important as Che Guevara’s.