To be trans*, black, under thirty and still alive is, unnecessarily, a miracle in our world these days.

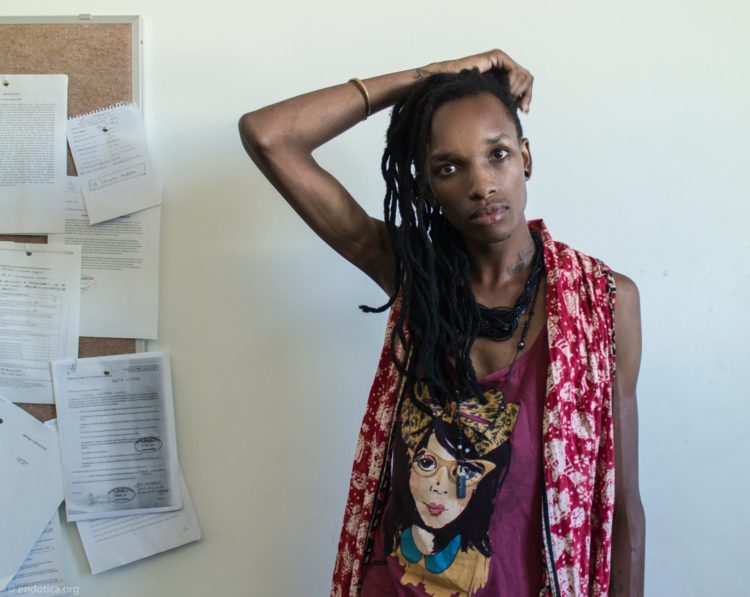

I’m Kat Kai Kol-Kes and I identify as many things, but when I was approached by TRUE Africa to share my story of growing up in Botswana in the 90s as a trans* person I found myself simultaneously baffled by where to start, and blank; almost as if I hadn’t grown up somehow.

Quite often memory gives way to fantasy – more so for me as a storyteller – but I’d like to think that I am about to offer a fair account of events in my life.

Many people have a knee-jerk reaction to finding out that someone is trans* identifying.

I must preface this story of becoming ‘Botswana’s first openly Trans* identifying public figure’ by saying while I divulge a substantial amount of material going toward my (eventual) autobiography, I’ve kept some of the juicy bits out – like why ashen green eyes will forever be my weakness, or why one February 13th was the start of the most anxiety-filled three days of my adult life – but I’ll let you in on breaking my drag virginity as a child, that one night I (literally) lived out PCD’s Don’t Cha, and realising that African, Christian, Artist, Pole Dancer, Skinny and Intelligent can combine, like the elements making up Captain Planet, to create a revolutionary force: a ‘Black Woman of Complications’.

(WARNING: The 80s, penises and boobs feature quite a bit in this story.)

Many people have a knee-jerk reaction to finding out that someone is trans* identifying. The question fired at you almost immediately is: ‘So, when did you know?’ I’ve never really known how to answer this question; I didn’t know I knew until I was too old to remember when I knew. Somewhere along the line, the world’s perception of me and my perception of my place (and presence) in the world ended up being what we call transgender.

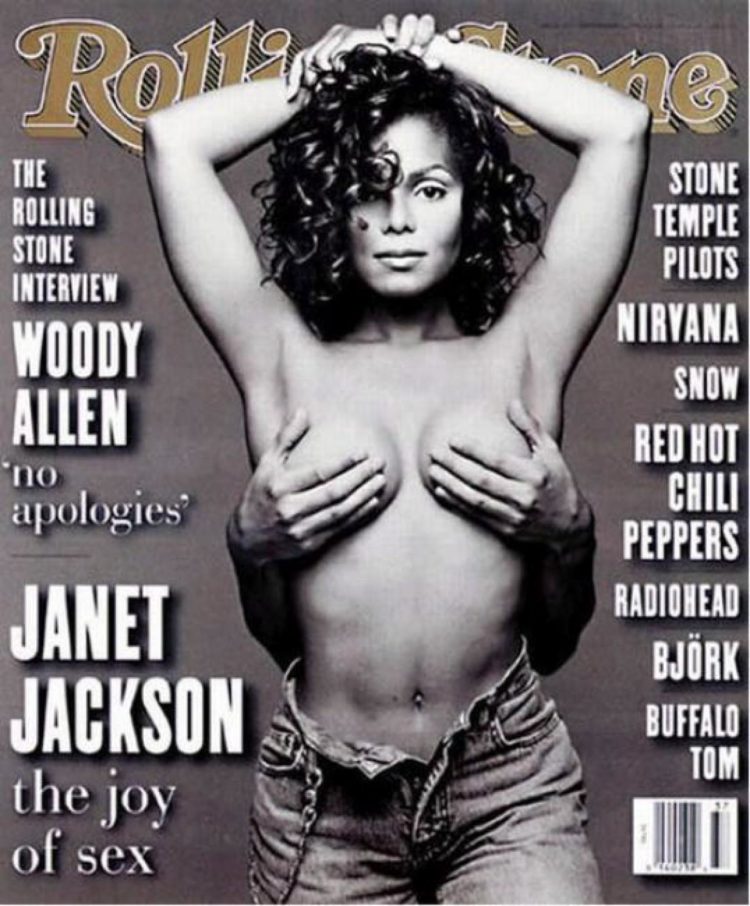

On a rainy, African summer day in January of 1988 at Jubilee Clinic in Francistown, a child with a penis was born to a young unmarried couple – an accountant and mathematics teacher. It was a Wednesday. This happened a year before Janet Jackson released her prolific Rhythm Nation 1814 album – at once an iconic historical event and central to the story of my life.

I’d describe my family as religious, traditional, musical, and excellence driven.

I’d describe my family as religious, traditional, musical, and excellence driven. Though, of the memories I have of my dad, I don’t recall ever being in church with him, that was where my mom and I hung out; and it’s still part of how we relate to each other today. Being the last addition to the family, I enjoyed both the adoration and scrutiny of my parents (by virtue of living in the shadow of my older brother) – another thing that bonds me with Janet Jackson.

We had an open and jovial household. One of my fondest memories is of Saturday mornings spent in the kitchen making breakfast. I was barely tall enough to see above the kitchen counter but I’d always stand by and help whisk the batter and watch my dad flip pancakes; always amazed at how they’d take to the air and spin and he’d always catch them. I am still those pancakes.

I also fondly remember toiling away with my mother at my grandparents’ cattle post – a physical space which I’ve grown to realise formed a significant impression on how I crafted myself into the ‘Black Woman of Complications’ I am today. This mix of suburban, modern living and traditional culture means I’ve never been able to look back and pinpoint when I most definitely knew I was trans*.

My earliest, most vivid encounter with the gender system happened in my standard 2 classroom at Clifton Primary school in 1995. We used to have a weekly show and tell session and I remember the excitement of contemplating what to bring to elicit envy or admiration from your classmates.

The boys would bring things like action figures, sticks and animals to Show and Tell; the girls would bring dolls and My Little Pony figurines and have fantastic stories to tell. I quickly found myself in a quandary. I was equally comfortable bringing my Sauropelta toy (it’s a dinosaur), as I was with bringing the doll (not a Barbie, because they were ridiculously expensive) which I had to beg and cry for in the Spar before my mother would relent and buy it. Yes, I know what you’re thinking: ‘She had a dinosaur?’ You see, along with dolls, I was enthralled with my DK book collection which included books on dinosaurs, trucks, and aeroplanes. So when I wasn’t hand crafting new clothes for my dolls from fabric scraps I got from my mom’s tailor friend, I was growling and roaring playing with my dinosaurs.

This was to become my first time performing in heels in front of a crowd.

The year my father passed on, our teacher asked us what we wanted to be when we grew up. I replied: I want to do drama! My classmates wanted to be doctors and fire fighters but I’d realised that acting and theatre gave me the chance to create myself a million times over.

While I was book smart, I also wanted to live out my creativity to the max. Why not? My father was a guitar-playing, karate-fighting mathematician; and his partner, my mother, was a field-tilling, church choir-singing accountant.

Having these two people as examples of letting your passions co-exist made me think being smart and being creative didn’t have to be opposites in my life the way they had been portrayed on television – and boy did I watch a lot of TV. I was going to become Jean-Claude van Damme, and Jem from Jem and the Holograms.

A wild example of how drama shaped my life is when I was 12 and had to fill in for a friend of mine in a play – a cover I still have a sneaky feeling she orchestrated as a test/favour for me. As part of a Setswana traditional showcase day at school, we had been rehearsing a play about a sneaky child and a hot-tempered, single mother – the moral of the story being about heeding parental wisdom and guidance.

I was already involved with the dance troupe and 20 minutes before the play, I was asked if I could fill in as the mother. This was to become my first time performing in heels in front of a crowd – until the age of 15 I could still fit into my mom’s shoes and strutted throughout our house on many occasions when I was home alone.

TV is also where I met the love of my life, my icon, and (still to date) my mentor and guiding light, Janet Jackson.

The sensation of donning that wig and red dress and heels and feeling comfortable on stage delivering my performance and being applauded for it by my peers and their parents and complete strangers, was possibly one of the most nerve-racking yet liberating things I’ve ever experienced. I’d had my taste of being like someone I’d seen on TV: RuPaul.

TV is also where I met the love of my life, my icon, and (still to date) my mentor and guiding light, Janet Jackson. The 90s was a great time for music TV shows and we were never short of servings from Ms Jackson. From watching her dance to funky beats – think Rhythm Nation and Pleasure Principle, to envying her style – fearless movement between sexy, easy-going and 80s powersuits in Alright and Escapade, to seeing that broad and radiant smile – think Love Will Never Do (Without You); I was enamored with the youngest Jackson; but I was always confused about whether I wanted to be with her or be her.

One particular issue of DRUM magazine had a pull-out centre-fold of Janet with her curly ombre locks, full chest, killer abs and showed off the top of her Mickey Mouse tattoo. I remember thinking to myself: ‘I can’t wait to have boobs like that.’ Yes, I’d heard about Janet’s boob job but I, somehow, just expected mine to grow like that naturally.

Another person who had the same effect on me at that age was Mel B with her tattoos and tongue ring and feisty attitude as Scary Spice. These two black women were boisterously owning every space they occupied, being game changers and had the real-life bodies I honestly thought I was going to have once puberty hit.

Cut to a 13-year-old me happy that I was going into high school, having already had my first kiss with tongue (behind the science lab, as a result of honouring a dare) and I could still hit my soprano notes, and my greatest fear – growing facial hair – hadn’t yet become a reality. I would giggle quietly as people would correct themselves after complimenting my mother on such a beautiful daughter. But the butterflies in my stomach transformed to dragons; I started to realise that my body wasn’t listening to my prayers and doing what my girl friends’ bodies had, almost magically, done over the Christmas holidays.

Hoping that I’d mythologically re-programme my body, I woke early one morning in my early teens to sweep my chest.

When I was about nine or 10 years old, my 12-year-old cousin moved in with us. There’s a practice in Setswana culture where girls becoming women are to wake up in the morning before sunrise and prepare to brush their bare chests with a grass broom to calm the pain of their developing breasts. I overheard an aunt of ours talking about it. Guess who tried it? Hoping that I’d mythologically re-programme my body, I woke early one morning in my early teens to sweep my chest. At one point I genuinely thought my body had listened and was secretly developing breasts, as I could feel something when I grabbed my areolas. This sent me into another panic because I didn’t know if I could handle them. Needless to say, I have never shared this story until now.

While American TV shows set in high schools sold me, and an entire generation of African youth, a dream of what the experience would be like (Yes, I’m talking about you Sabrina the Teenage Witch, Saved by the Bell, FAME, Kenan and Kel, etc.) being a teenager wasn’t as tough for me as it could have been. I never really had to navigate being a queer teen until the last couple of years when the landscape got a lot less ‘straight’.

I began, willingly yet surreptitiously, to allow myself to enter queer spaces. I befriended the notorious teen lesbian in town whose crew was the baddest when it came to inter-school membership and felt like a family. And while I was out in the streets picking up scintillating nuggets of ‘sin’, I realised the 8-year-old me saying: ‘I’m not gay’ was telling the truth.

Throughout primary school I’d been a star on stage, in class, on the tennis court, in the swimming pool, on the sports field – you name it, I was there and right at the front. I enjoyed being on the football and hockey teams as much as I loved learning how to crochet and ballroom dance. In high school I could fit in any- and everywhere (which I did) but now I realise that this was part of the protection system I created for myself.

I couldn’t be bullied if I was one of the coolest kids around. Yet, with age I’ve learned that this coolness also comes with its fair dose of loneliness. But during tough times, it was both my biological and queer family who worked together to keep me together.

The next portion of this (all too big) story talks about just that; the human interactions which have created this ‘Black Woman of Complications’. From our break-time spoken-word battles with the guys, to the guy who worked at the grocery store and unabashedly hit on me in front of my friends, I had to deny that it thrilled me.

I knew, at age 16, that I was still smart yet creative, not gay, I didn’t have facial hair, and I was (apparently) attractive, but still didn’t quite know when the boobs were going to arrive or how. Funnily enough, though, today the arrival of my boobs is the last thing on my mind thanks to Janet Jackson and Lupita Nyong’o.