In the last year, two cases of alleged police brutality have caused large protests in the French capital. On 19 July 2016, 24-year-old Adama Traoré died while in custody. In Febrary 2017, four officers were charged after 22-year-old Théo Luhaka was allegedly raped with a police baton in a suburb of Paris.

On April 23, France will find out which two candidates will progress to the second round in the upcoming presidential elections. There is a good chance that Marine Le Pen, a far right candidate, might win the first round. She has been gaining in popularity since she took over leadership of the National Front from her father Jean-Marie Le Pen five years ago.

French artists are using their canvases, cameras and their influence to send powerful messages against racism and police violence

In the context of this, and in bid to pay tribute, raise awareness, speak up or simply ask for justice, French artists are using their canvases, cameras and their influence to send powerful messages against racism and police violence.

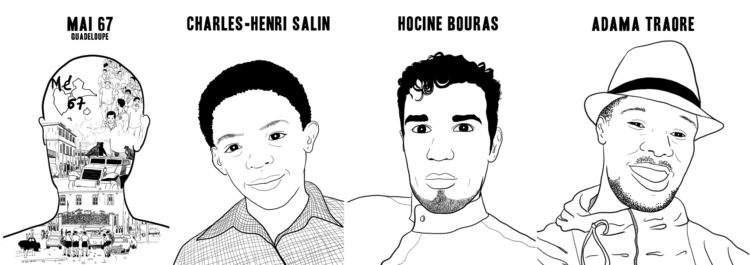

The artist collective Cases Rebelles produced a series of black and white posters remembering victims of police violence and institutional racism. These were held aloft at the March for Dignity on March 19 in Paris.

The march was called to demand respect for the rights of all French citizens–whatever their faith or colour–and to call for the fair application of justice–without exception–by the police.

Xonanji, an artist who is part of the Cases Rebelles collective, is influenced by Oree Originol, an American activist. Xonanji’s work commemorates the ninth anniversary of the death of Lamine Dieng, It was organised by the group ‘Vies volées’ [Stolen Lives].

It also acts as a creative workaround to the lack of good-quality photographs of some of the victims. The book 100 Portraits contre l’Etat Policier gathers the stories of 100 people who died between the years of 1947 and 2016 as a result of police violence.

Director Ladj Ly insists that he is not a spokesperson, even after he won an award at the Clermont-Ferrand festival, which specialises in short films, for Les Miserables. This movie, which hovers between fiction and reality, is inspired by personal experience when he was a young cop watcher living in Montfermeil. A member of the film collective Kourtrajmé, he has been filming the French suburbs for over 20 years.

His camera has acted as self defence, appeasing both policemen and young people. Ladj Ly was able to film as an insider the 2005 riots in his documentary 365 jours à Montfermeil. It was praised everywhere but in France.

A famous scene shows the inability of the press to understand and provide a voice to young people. 10 years later, Les Misérables was bought by TV channel Canal+.

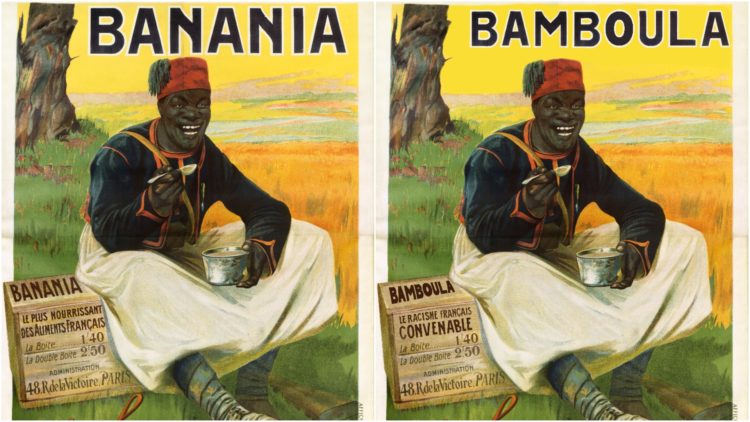

Street artist Jaeraymie wants to show how racism has deep roots in French society. The advert for a popular chocolate drink called Banania already sparked controversy because of its caricatural depiction of Africans. A spokesperson for the policemen recently stated on TV, that police use of the word ‘bamboula’ could be tolerated during checks.

Fear and normalisation are sought by the current French government

The origin of the word bamboula is ‘tambourine’ in Guinea and in the last century in France it has become a derogatory term for Africans. In response to this, Jaeraymie took the poster of a Senegalese soldier (a ‘tirailleur sénégalais’) smiling and replaced the word Banania with Bamboula.

He pasted it in Parisian streets as part of a street art campaign organised by another artist, Combo Kulture Kidnapper. Did the artwork grab the attention of the public? Yes, but after couple of days it was taken down. ‘I needed to catch the eyes of people who are not concerned about these issues,’ Jaeraymie explained to me.

‘Fear and normalisation are sought by the current French government. For them, silent minorities should not raise their voice. But to me, all French citizens are accountable to speak up and should not be afraid to do so.’

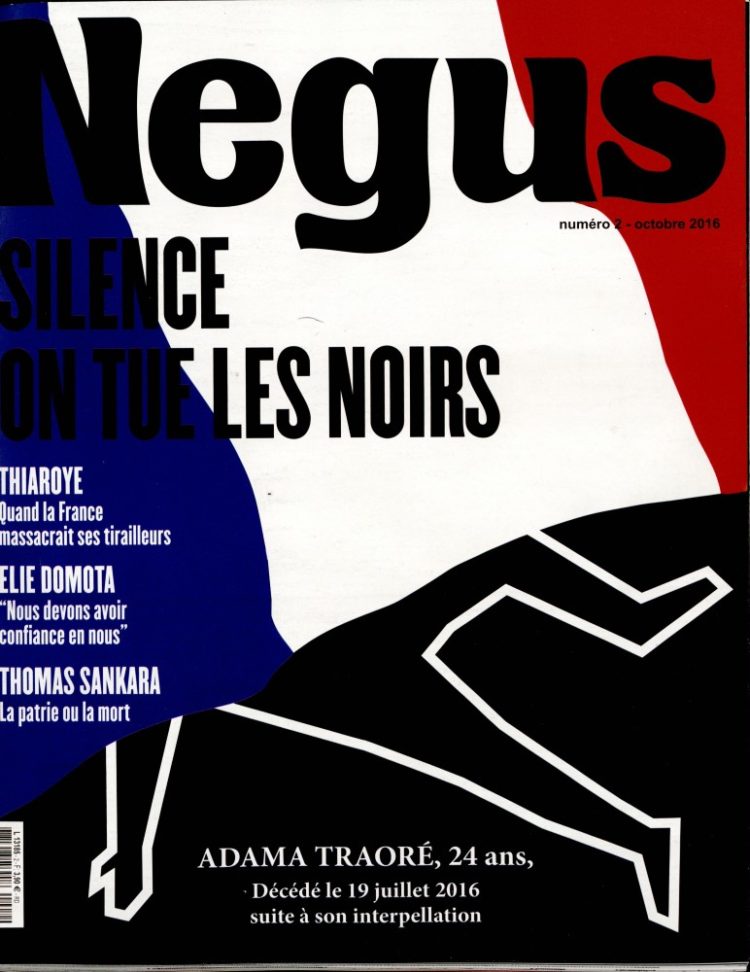

Speak up and you may face a ban. The editors of the magazine Negus Journal reported on their Facebook page that there would be a delay in publishing their second edition because, they alleged, the cover had not been ‘validated’ and had received a warning stating that it was ‘anti’ the French Republic. The magazine was eventually released.

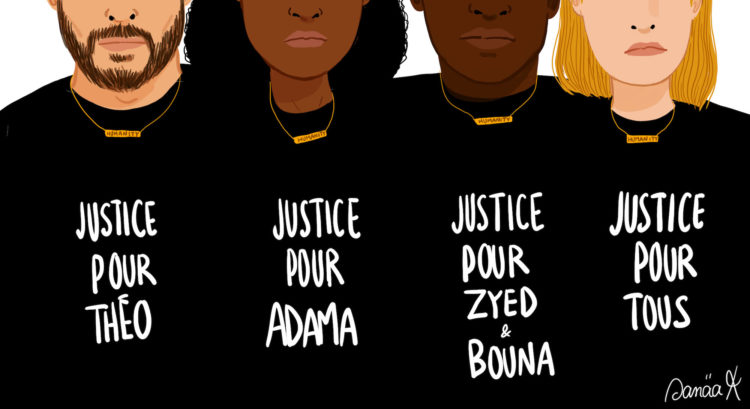

Women are also affected. Two illustrations by Sanaa K were widely shared on social network. Amongst them, her portrayal of Assa Traoré, the sister of Adama Traoré, shows that women are also victims.

The mural Brothers and Sisters in Humanity was available for free download on Flickr. The banner became a cover for many on social media. Sanaa K regularly uses her wide social presence as platform to debate social injustice.

The French pop-soul singer Imany–whose family come from the Comoros islands–used her performance at Les Victoires de la Musique, an annual French award ceremony which rewards achievement in the music industry. In her speech, she stated that part of the privilege of being an artist is to be the voice of deprived. She asked for justice for Théo and Adama. She also condemned all forms of violence.

During the Césars, which are France’s national film awards, filmmaker Alice Diop, who won the prize for best short film Vers la Tendresse, followed Imany’s lead. She dedicated her prize to the victims of police violence.

The journalist and author Claire Diao of Double Vague, le nouveau soufflé du cinema français (to be published in May 2017) concludes that an emerging wave of directors is giving a voice to issues which are not normally dealt with in mainstream cinema.

These filmmakers, artists and illustrators are giving a voice to those who don’t have one.