In Nigeria, complaining seems to be a national sport. We complain about our lip service to democracy. We complain about our public officials who do not see the service that public service requires. We complain that they appear to use their office to benefit themselves, their families and – for the really patriotic – their villages. We are taken aback when those who set the conditions with which the rest of us have to live seem unable to understand the concerns of average citizens. ‘Enough is enough!’ ‘Bring back our girls!’ – we are always chanting for one thing or the other, yet no one seems to be listening. But is this behaviour surprising when we consider how many Nigerians are brought up?

I used to think the ‘Prayer for Nigeria in distress’, which I recited dutifully every Sunday growing up in the Catholic faith, was something that every Catholic around the world shared. Imagine my surprise on moving to the UK and when I found that this was not universal Catholic doctrine.

We love to say that charity begins at home, well so does democracy.

It’s difficult to be truly shocked that 17 years after the demise of military rule in Nigeria, we still feel the need to say the prayer. How can we expect a true democratic outcome on a macro level when we look at the cultural elements in microcosms of Nigerian society with which we grow up? One of the basic tenets of democracy is participation, and this involves listening, speaking and receiving feedback freely. However, at the household and community level it is not uncommon for children (and, sadly, sometimes women) to be told ‘Come on, shut up! Don’t talk when your elders are talking,’ or ‘Don’t question the adults! What do you know? You are a small girl.’ Yes, respect is necessary, but are we spreading an autocratic mindset?

When small girls and boys become big girls and boys, why would they act differently? Why would they listen, in a democratic sense, when we have raised them to believe that wisdom belongs to the elders, the men, or whoever holds the power? We have taught our children to shut up and do as those who are ‘wiser’ tell them. We have stifled creativity and the spirit of questioning the status quo. A damaging result of this behaviour is that we have groomed leaders that think that they do not need to be questioned, that it is solely for them to decide a course of action, based on their esteemed positions. Where is the democracy in this thinking? We love to say that charity begins at home – well, so does democracy.

The only way to escape the daily drudgery of being a junior at a Nigerian boarding school is to ally oneself with a powerful senior.

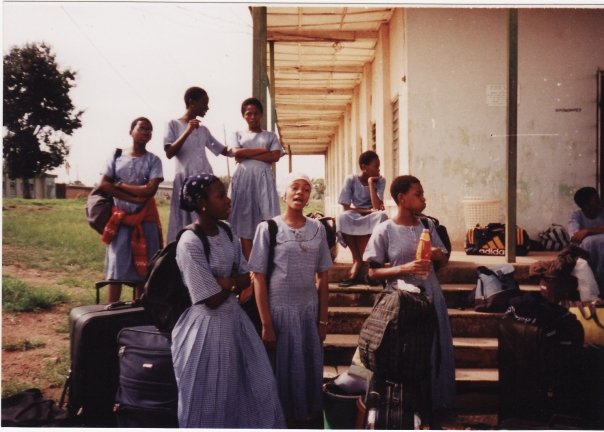

Following on from the home and community level, one of the hallmarks of a Nigerian upbringing is the boarding-school experience. There are the Federal Government Colleges, many of which are sadly fading from their glory days and becoming institutions with tales of underfed and over-punished children. At the other end of the spectrum, we have the ‘Ajebota’ institutions, where the annual tuition costs start from about five times the GDP per capita of the country. Around them swirl tales of hypersexed and over-entitled little ‘ogas’ and ‘madams’. Or there are the austere religious institutions, with their conviction that teenage sexuality must be quashed through fear stories (with graphic pictures a bonus) of AIDS and unwanted pregnancy.

These fine institutions may differ in tuition, quality of education and abundance of food but one thing is common: senior domination. In Nigerian boarding schools, the ‘juniors’ are the bottom of the food chain. These are the youngest students from JS1 till JS3 (7-9th grade). As you go up through the grades, the more your power increases, until you get to SS3 and then you have really arrived: you are a ‘senior’.

Being a junior is not fun. You often eat last (and sometimes not at all, depending on where you fall on the FGC-Ajebota scale and the abundance of food at the school) and it is your duty to ‘help’ the seniors with such tasks as laundry, fetching hot water (a luxury) to bathe, carrying books and running errands. During compulsory weekend dorm cleanings, as a junior you can forget about such luxury tasks as mopping and dusting! Your jobs will include scrubbing floors, cleaning the louvres, sweeping, and if you claim asthma, you can clean the toilets.

This Wolf of Wall Street tweet sums up being a senior for a lot of Nigerians:

The only way to escape the daily drudgery of being a junior at a Nigerian boarding school is to ally oneself with a powerful senior (head prefect, dorm prefect or the queen bee that everyone knows not to mess with). Once everyone knows that this is ‘your’ senior, you will be exempt from the usual misery of being a junior and your mates will look at you enviously and wish they were in your position. You have to be careful not to pick the wrong senior because you have tied your fate to theirs. You will bear the brunt if they fall out of favour and lose the respect of their peers. Your immunity can vanish in a flash and it may be impossible to recover, depending on how you behaved during the glory days.

So why then, do we wonder why those in power in society see it as the reward of their position to reap the most benefits?

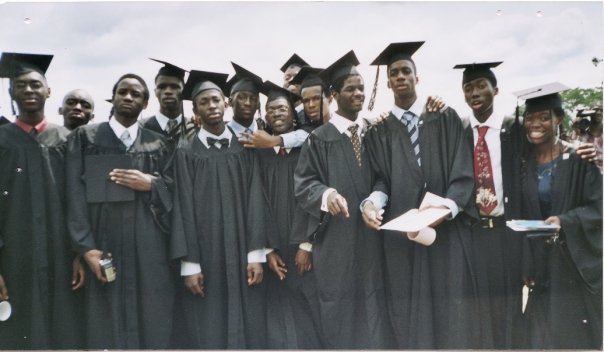

The juniors accept their sad fate; they wait for their turn, that day when they too will be seniors and have access to the biggest piece of meat at lunch and an army of juniors to carry out their menial tasks. They rarely revolt; rarely report bullying to teachers or even parents. They accept their lot and wait patiently for the day that they will become the oppressors. From the outside, this all seems ridiculous. Surely the logical thing to do as a junior would be to call such behaviour to the attention of teachers and parents. But caught in the thick of it, most people don’t consider it an option.

So why then, do we wonder why those in power in society see it as the reward of their position to reap the most benefits? Is it surprising that a lot of people, instead of channelling their energy towards fighting a broken system, are clamouring for favour and waiting for their turn to enjoy such a position?

I’ve picked two random situations to highlight a problem of culture that exists in many spheres of our society. There are thousands of others. The first step towards solving a problem is fully to acknowledge it, and so we must extend this type of analysis to every situation. The only way we can chip away at these massive cultural problems that are holding us back is to fix those at the root: start from the seemingly innocuous situations that are breeding a dangerous attitude in our citizens and future leaders. Perhaps if we could intervene earlier, make our homes, schools and other ecosystems safe bubbles where selflessness, critical thinking and creativity are embraced, we wouldn’t have this mindset escalate to a national scale. Imagine what impact that could have!

Think that Nigerians owe their attitude to their education? Tell us your take using the hashtag #TRUEAfrica.