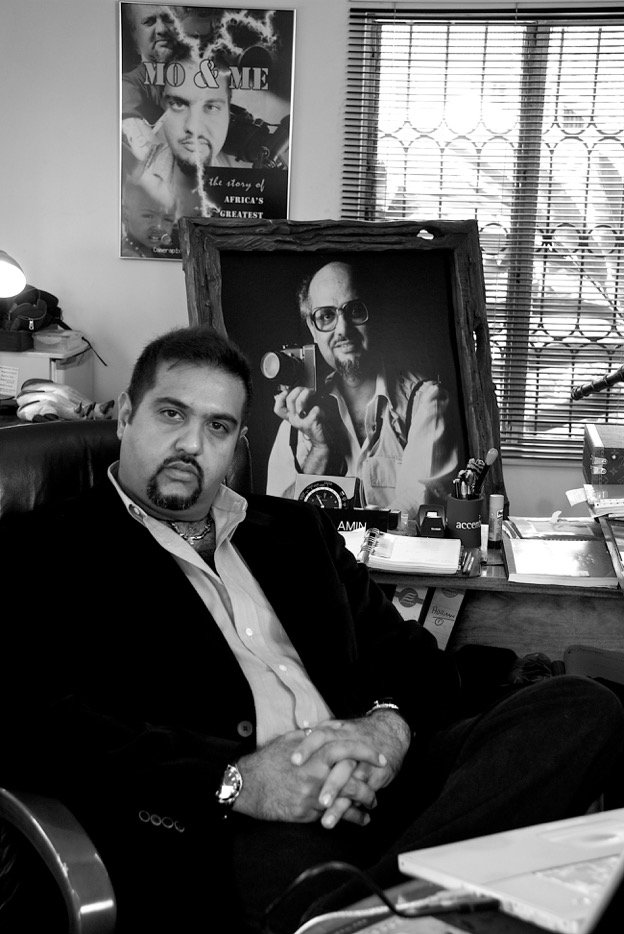

Salim Amin, 46 years old, is a big man; he stands with an imposing girth. The man likes tweed jackets over denim and confines his feet in leather laces ups shipped in from Banana Republic.

Salim has a thing for bling. And when you come close to him, it wouldn’t be hard to notice his thick eyebrows just like his father, and a determined balding pate sliding from the rear.

He’s the chairman of A24 Media and Camerapix, a video and photography production house that was founded by his father more than fifty years ago.

Now Salim is on a mission.

There’s a certain air of pride that flickers out of him when he speaks about his father, you can tell by how animated he gets. He’s the only child of Mohamed ‘Mo’ Amin – Africa’s greatest photojournalist whose influential images moved the world.

Now Salim is on a mission. ‘I get inspired by a lot of things,’ Salim enlightens. ‘My father’s work and achievements are always at the back of my mind. Now it is the opportunity I see amongst young journalists in Africa that have new platforms to work on and the enthusiasm they have for telling stories’.

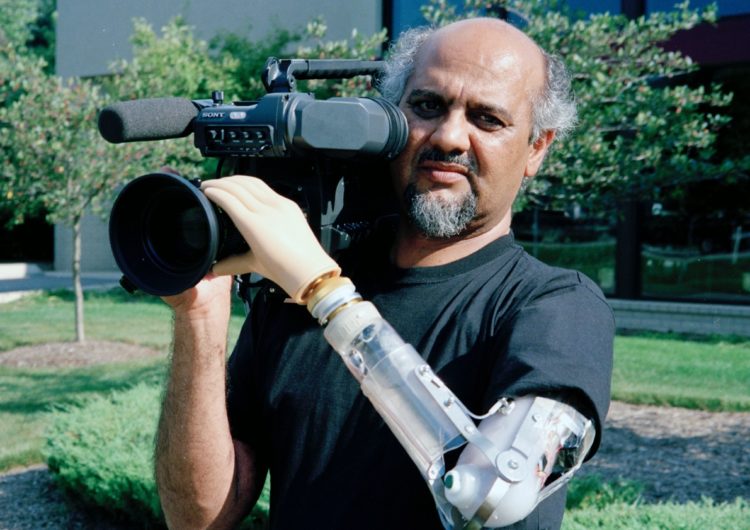

When he was young, Salim accompanied his father when he went out for assignments; from him, he learnt the basics of camera work. Hands tender at taking good images, Mo was by his side and showed him the importance of understanding beauty of photography – the transformative technicality of the lens – and of bringing life into shape.

Mo was a very busy man.

It is this bond that has shaped Salim into who he is right now, but that’s only the half of it, Mo was a very busy man. He was out of the house for weeks which had a lasting effect on Salim.

‘I looked up to him but I really didn’t know him and what drove him until I made MO & ME –the award-winning documentary. It is then that I understood why he did what he did, the passion and commitment he had,’ Salim enthuses. ‘I have learnt to be a better father to my children, to be more involved in their lives, but I also know that his passion and commitment have inspired me to be a better leader’.

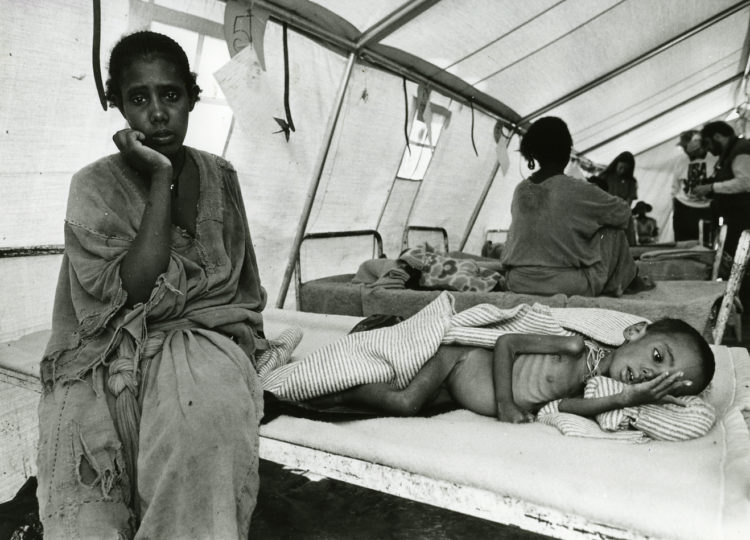

Among renowned photojournalists on the African continent, no name surpasses Mohamed Amin’s. His photos shot with a masterly touch offered a spectacular account to the world; a perspective of real-time events that helped shape the daily political, social and economic life of Africa’s inhabitants. From dictator Idi Amin’s brave poking at colonialism to capturing a boy strutting a live crocodile on his shoulders, Mo’s eye for detail and creative poise shines through.

What would his father think about the state of freedom of expression in Africa?

‘I think he would be disappointed at how media freedom in Africa has not reached its potential; the fact that there is still so much censorship in many countries around the continent with journalists being imprisoned and killed with impunity is something that he would be very disappointed in.’ Even so Mo would be hopeful. ‘He would be encouraged by all the new media that has become available – the new platforms that are now out there for African journalists to tell their stories’.

It is from this foundation that Salim wants to create his own by nudging beyond his father’s legacy.

‘My father’s name and shadow had a lot to do with me being recognised, or at least being given opportunities to do certain things. I would like to think that after those opportunities were given I proved that I could do things as well as him’.

Before Mo died in a plane crash twenty years ago, he founded MoForce, a film production training institute that is geared to training young aspiring filmmakers for a career in journalism and film by offering partial and non-partial scholarships. Now the son is expanding his father’s vision by working with Multimedia University in Nairobi to offer this training.

A24 Media embodies part of the future of African content provision.

Salim says, ‘We also are pushing heavily into education and the development of a masters degree in broadcast journalism.’

With more than two dozen employees, and an archive of over three-million images from different places on the continent and in the world, A24 Media embodies part of the future of African content provision.

Salim wants to offer a different narrative by producing news worthy stories and programmes that sound and look good to the African eye and ear. Stories that are told by Africans themselves to the rest of the continent and the world.

We are producing some the best and most unique content on Africa.

‘At this point the central focus of all our efforts is to grow and expand A24’. He says. ‘We are producing some the best and most unique content on Africa and we are looking at all the different platforms to distribute this and hopefully earn decent revenue’. He adds. ‘We will continue to produce this unique content and work with our historical archive to create new and exciting content’.

Named Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum in Davos 2005, he believes Africa’s time to shine has come.

‘People often want to talk about Africa and its history as if it died with my dad years ago,’ He continues. ‘The fact is, Africa is always changing and the past hard news has given way to a bright future and my dad’s legacy lives on. Mo was once the story and Africa’s wars and corruption were the narrative.’

Governments have to recognise the importance of content producers.

He changes tack. ‘That’s the reason I started my own show – The Scoop, it’s something my dad could only dream about; he had envisioned shows that are no longer pegged on war and corruption but crafted for the modern African viewer like Upbeat or our CCTV documentary series – Faces of Africa’.

Salim urges the state machineries in the continent to do more.

‘Governments have to recognise the importance of content producers in their countries and work with them and enable them tell real stories about Africa’. He goes on. ‘We are the best medium for promoting achievements, successes and beauty of our countries and continent at large, and governments need to see this and work with us not against us’. He insists. ‘They should put resources into training and nurturing young talent and give them a creative space to work in’.

For now, this is what Salim wants to be remembered for: he wants to be remembered for being a good father to his daughters – to be there when they need him most; he wants to be remembered for sharing native African stories with a beauty that exceeds beyond poverty, war, disease and ruin that for years have plagued its borders; he wants to be remembered for transforming the modern African storyteller and equipping them with the necessary tools that’ll make them competent at their craft; but above all, Salim wants to be remembered for leaping beyond his father’s dream.

If I manage to help tell some of the great untold stories of this continent, then I will feel that I have contributed.

‘Let me go down the pages of history as someone who tried to change the conversation about Africa, who tried to change the perception of the continent, who tried to change the image many people have of Africa’. He finalizes. ‘Because if I manage to help tell some of the great untold stories of this continent, then I will feel that I have contributed something to the unfolding African story and help build my own legacy distinct to my father’s’.